Mark Meadows’ Proffer

I continue to dig through the document dump Judge Aileen Cannon finally released the other day.

The dump included 70 exhibits (some FOIAed documents) submitted in conjunction with Trump’s motion to compel discovery and a few exhibits submitted with the government’s response.

The most titillating of the latter set is a November 2022 interview with Person 16 (whom I suspect to be Eric Herschmann, in part because Herschmann relishes giving titillating interviews in which he calls other lawyers morons).

But for the moment, I want to look at Person 27’s December 2022 proffer.

While the government is coy about the identity of Person 16, they’re not hiding Person 27’s identity: It is Mark Meadows.

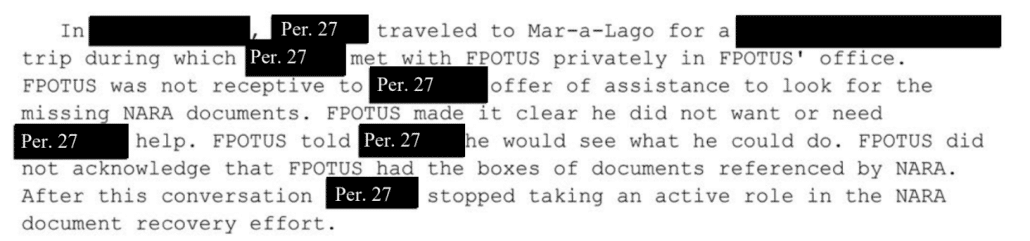

The passages below, matched to the corresponding exhibits, makes it clear that Person 27 is Trump’s former Chief of Staff. Said Chief of Staff briefly got involved in the document recovery effort after NARA first threatened to make a referral to DOJ, then threatened to deem the boxes Trump had taken destroyed. Said Chief of Staff traveled to Mar-a-Lago in October 2021 (at a time when discussing the January 6 investigation would have been fruitful) and while there asked if Trump wanted help searching boxes, only to be told that Trump didn’t need help returning documents he wanted to keep.

A succession of Trump PRA representatives corresponded with NARA without ever resolving any of NARA’s concerns about the boxes of Presidential records that had been identified as missing in January 2021. By the end of June 2021, NARA had still received no update on the boxes, despite repeated inquiries, and it informed the PRA representatives that the Archivist had directed NARA personnel to seek assistance from the Department of Justice (“DOJ”), “which is the necessary recourse when we are unable to obtain the return of improperly removed government records that belong in our custody.” Exhibit B at USA-00383980; see 44 U.S.C. § 2905(a) (providing for the Archivist to request the Attorney General to institute an action for the recovery of records). That message precipitated the involvement of Trump’s former White House Chief of Staff, who engaged the Archivist directly at the end of July. See Exhibit 4 Additional weeks passed with no results, and by the end of August 2021, NARA still had received nothing from Trump or his PRA representatives. Id. Independently, the House of Representatives had requested Presidential records from NARA, further heightening the urgency of NARA obtaining access to the missing boxes. Id. On August 30, the Archivist notified Trump’s former Chief of Staff that he would assume the boxes had been destroyed and would be obligated to report that fact to Congress, DOJ, and the White House. Id. The former Chief of Staff promptly requested a phone call with the Archivist. Id.

[snip]

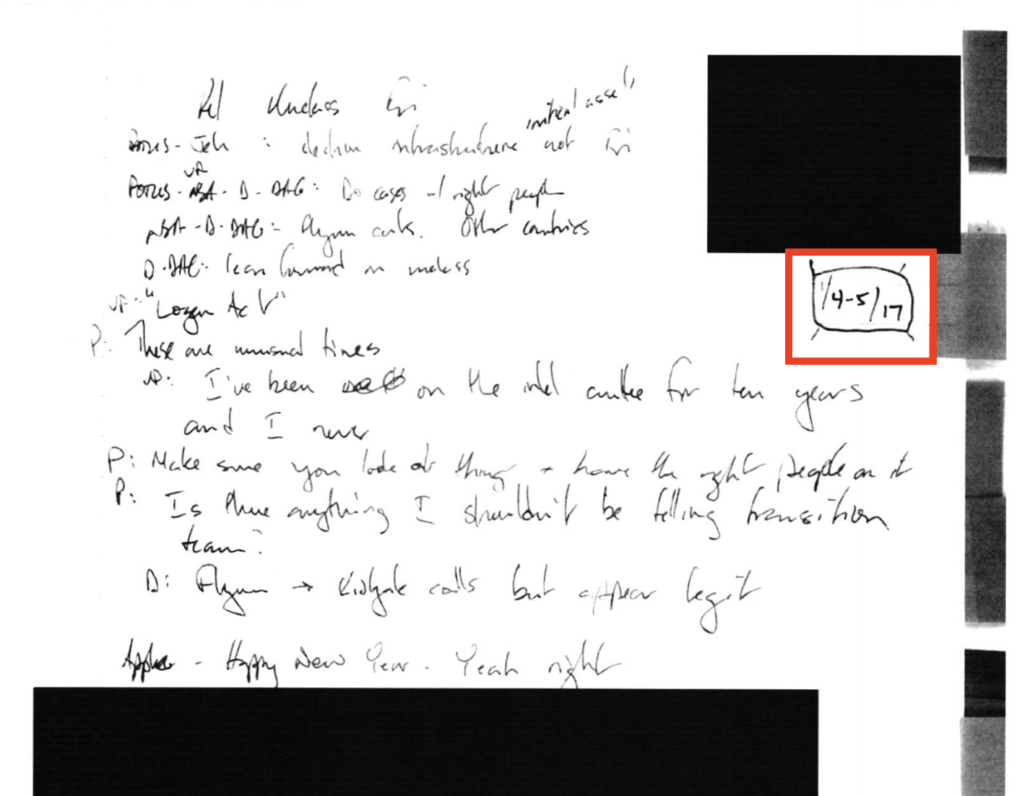

Fall passes with little progress in retrieving the missing records. In September 2021, one of Trump’s PRA representatives expressed puzzlement over the suggestion that there were 24 boxes missing, asserting that only 12 boxes had been found in Florida. Exhibit 7 at USA00383682, USA-00383684. In an effort to resolve “the dispute over whether there are 12 or 24 boxes,” NARA officials discussed with Su the possibility of convening a meeting with two of Trump’s PRA representatives—the former Chief of Staff and the former Deputy White House Counsel—and “possibly” Trump’s former White House Staff Secretary. Id. at USA-00383682. On October 19, 2021, a call took place among WHORM Official 1, another WHORM employee, Trump’s former Chief of Staff, the former Deputy White House Counsel, and Su about the continued failure to produce Presidential records, but the call did not lead to a resolution. See Exhibit A at USA-00815672. Again, there was no complaint from either of Trump’s PRA representatives about Su’s participation in the call. Later in October, the former Chief of Staff traveled to the Mar-a-Lago Club to meet with Trump for another reason, but while there brought up the missing records to Trump and offered to help look for or review any that were there. Exhibit C at USA-00820510. Trump, however, was not interested in any assistance. Id. On November 21, 2021, another former member of Trump’s Administration traveled to Mar-a-Lago to speak with him about the boxes. Exhibit D at USA-00818227–USA-00818228. That individual warned Trump that he faced possible criminal exposure if he failed to return his records to NARA. Id

[my emphasis, links added]

These passages, collectively, serve to rebut Trump’s claim that the involvement of Biden White House attorney Jonathan Su was in any way investigative or improper; the passage shows that Patrick Philbin involved Su, his successor as White House Deputy Counsel, and the White House had to further intervene when Meadows tried to reach out to a White House Office of Records and Management person, Person 40, directly.

This ABC story describing Meadows’ testimony, describing offering to help but being rebuffed, further corroborates that Person 27 is Meadows.

The former chief of staff also told investigators that shortly after the National Archives first requested the return of the official documents taken to Mar-a-Lago in 2021, he offered to Trump that he would go through the former president’s boxes to retrieve the official records and send them back to Washington. Meadows told investigators Trump did not accept his offer, according to sources.

So Government Exhibit C is a December 6, 2022 proffer from Mark Meadows.

I’m not so much interested in the content of that proffer. As ABC has reported, Meadows’ testimony was iterative, slowly evolving over at least three interviews as he was presented with more evidence of details that Jack Smith knew. Aside from a mostly redacted reference to Trump’s delegation of declassification authority (which may relate to the effort to declassify the Crossfire Hurricane binder and which might not be entirely true), the description of his trip to Mar-a-Lago to offer to help is the most interesting bit in this proffer.

But that’s the thing about proffers, offered by one of the best attorneys representing any Trumpster, George Terwilliger, offered before Beryl Howell overruled any Executive Privilege claims, and offered before the Georgia indictment made Meadows’ operative January 6 story told in DC less sustainable.

Proffers are the story you want to tell, not the full story.

As I wrote last August, after the first of ABC’s big scoops,

[T]his is not the testimony of a cooperating witness. It is the testimony of someone prosecutors have coaxed to tell the truth by collecting so much evidence there’s no longer room to do otherwise.

There are a number of things to which Meadows eventually testify, per ABC’s reporting, that are not in this proffer. The most notable pertains to his ghost writers, on which topic his testimony evolved to accept that they were probably right that Trump was sharing classified documents in 2021.

“On the couch in front of the President’s desk, there’s a four-page report typed up by Mark Milley himself,” the draft reads. “It shows the general’s own plan to attack Iran, something he urged President Trump to do more than once during his presidency. … When President Trump found this plan in his old files this morning, he pointed out that if he had been able to make this declassified, it would probably ‘win his case.'”

Sources told ABC News that Meadows was questioned by Smith’s investigators about the changes made to the language in the draft, and Meadows claimed, according to the sources, that he personally edited it out because he didn’t believe at the time that Trump would have possessed a document like that at Bedminster.

Meadows also said that if it were true Trump did indeed have such a document, it would be “problematic” and “concerning,” sources familiar with the exchange said. Meadows said his perspective changed on whether his ghostwriter’s recollection could have been accurate, given the later revelations about the classified materials recovered from Mar-a-Lago in the months since his book was published, the sources said.

According to ABC, where Meadows’ other testimony would evolve to is that he would have been more diligent than Trump returning stolen documents.

Meadows also told investigators that he would have responded differently than Trump when the National Archives first asked Trump to return all remaining presidential records in his possession, and would have been very diligent in his handling of the initial search for documents to return to NARA, sources familiar with the matter said.

It’s unclear if there’s an “if” involved in this conditional statement, such as “if he knew Trump was stealing classified documents.”

That’s interesting, because in that proffer, Meadows claimed not to believe Trump had Presidential Records at all.

In July 2021, [Philbin] informed [Meadows] that NARA had contacted [Philbin] regarding missing boxes of documents. [Meadows] was already planning to travel to Mar-a-Lago for an unrelated meeting and offered to look for the missing boxes while [he] was there. [Meadows] was skeptical there were any presidential records as [he] believed, based on [his] experience with FPOTUS at the White House, that the boxes likely only contained newspapers.

Again, there’s a pretty big chance that this particular claim evolved, just like Meadows’ explanation for why he edited a really damning description from his ghost writers. The proffer is a baseline, a place from which prosecutors could slowly coax testimony closer to the truth, all the while locking in useful testimony to rebut Trump’s most outlandish claims. In this case, after all, the testimony is critical to rebutting Trump’s complaints about the involvement of Su, whether or not the testimony was entirely forthcoming, even while not giving anything away.

And I’m interested in it for that reason as well.

This proffer doesn’t tell us how Meadows would later testify. It doesn’t give anything away.

Robert Mueller’s team tried to flip witnesses against Trump, only to find that Trump bought them off with pardons — something that Person 16 describes already got promised to Walt Nauta. Here, there’s a far larger cast of characters, including people like Meadows who are central to all of Trump’s suspected crimes and also likely to welcome an offer of a pardon in exchange for loyalty. This slow squeeze is a different approach.

And along the way, Jack Smith got useful testimony — testimony that will give him what he needs to go to trial — but testimony that also can be used to inch closer to the truth.