A seeming millennium ago, last Tuesday, DOJ’s Inspector General released a Management Advisory Memo describing the interim results of its effort to assess whether problems identified in Carter Page’s FISA application were unique, or reflected a more general problem with FISA. Based on the results from two prongs of DOJ IG’s ongoing investigation, DOJ IG believed they needed to alert FBI right away of their preliminary results in hopes they would inform FBI’s efforts to fix this and to offer two additional recommendations on top of the ones they made in December.

Unsurprisingly, a bunch of mostly right wingers have misrepresented the MAM. I wanted to use this post to explore what the MAM shows about the two prongs of investigation, the significance of the results, and the review of FISA generally. As a bonus track, I’ll talk about what role Intelligence Community Inspector General Michael Atkinson, who was fired on Friday, did not have in the FISA application reviews discussed in the MAM, contrary to what a bunch of wingnuts are claiming to justify his firing.

The universe of FISA

Before getting into what the review showed, some background on the universe of FISA may be helpful.

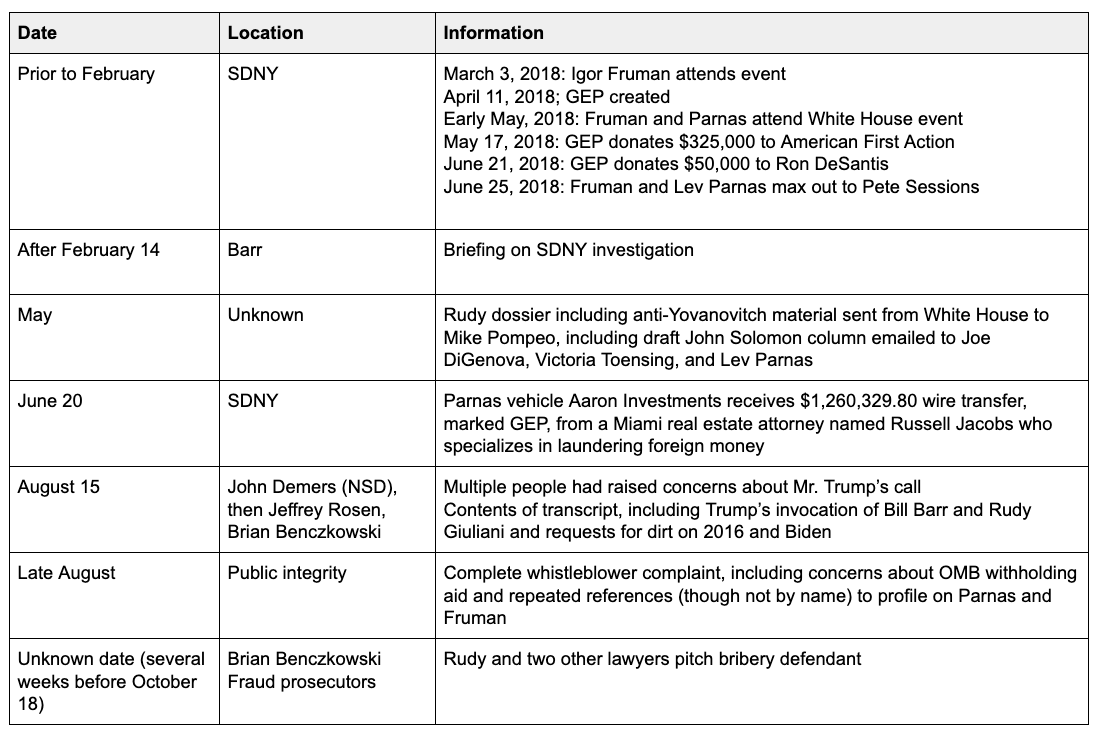

Both prongs of DOJ IG’s investigation examine probable cause FISA applications from 8 FBI offices submitted over the 5 year period ending last September (the end of Fiscal Year 2019).

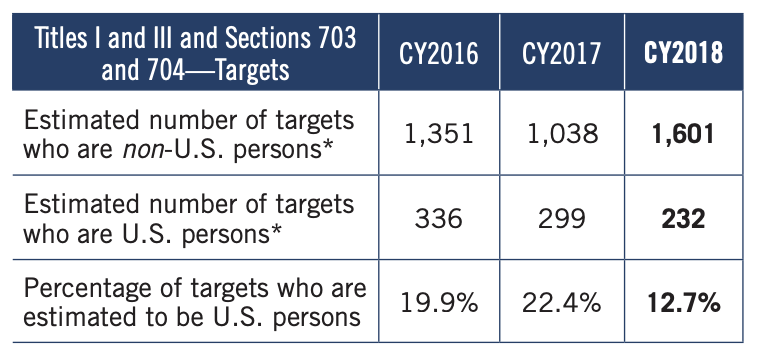

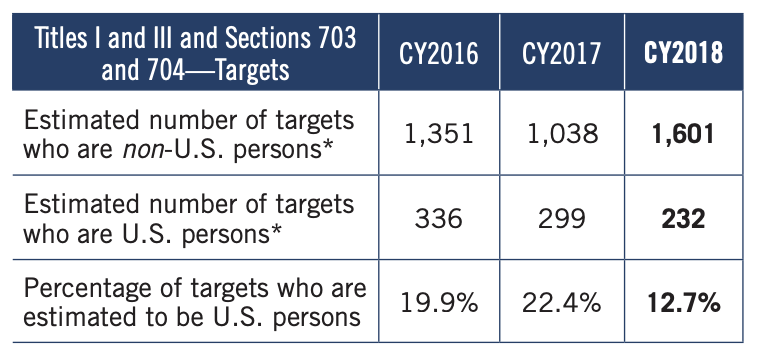

The last three years’ transparency reports from the Office of Director of National Intelligence have broken down how many of the probable cause FISA applications were known to target US persons. While there’s been some flux in the number of total probable cause applications, the ones targeting US persons have been going down (perhaps not coincidentally, as scrutiny of the process has increased), from 336 in CY 2016 to 232 in CY 2018.

Using 300 applications targeting US persons as an estimate, that says for the 5-year period DOJ IG is examining, there would have been roughly 1,500 that targeted US persons. The MAM says that the 8 offices included in the review thus far submitted more than 700 FISA applications “relating to U.S. Persons.”

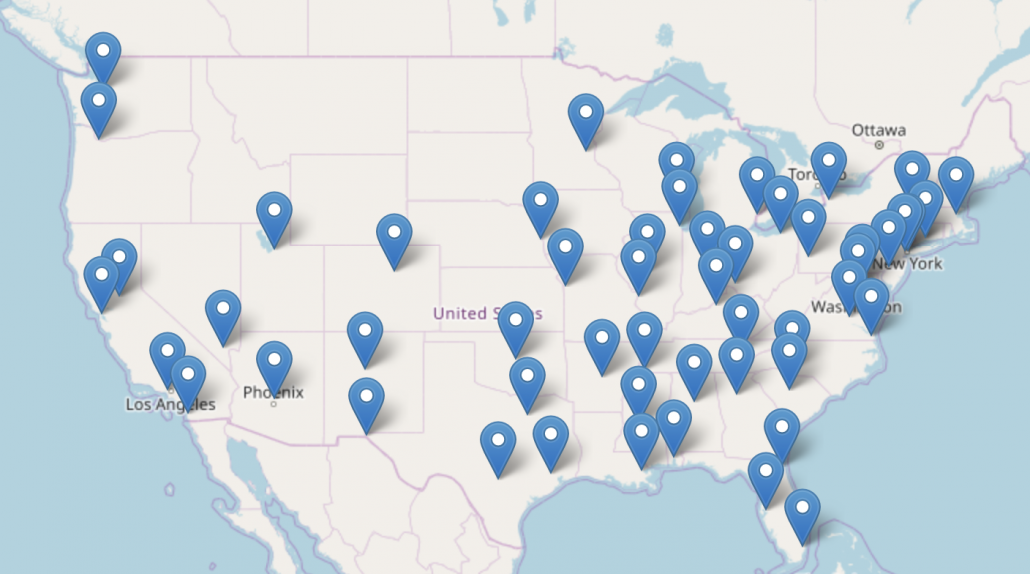

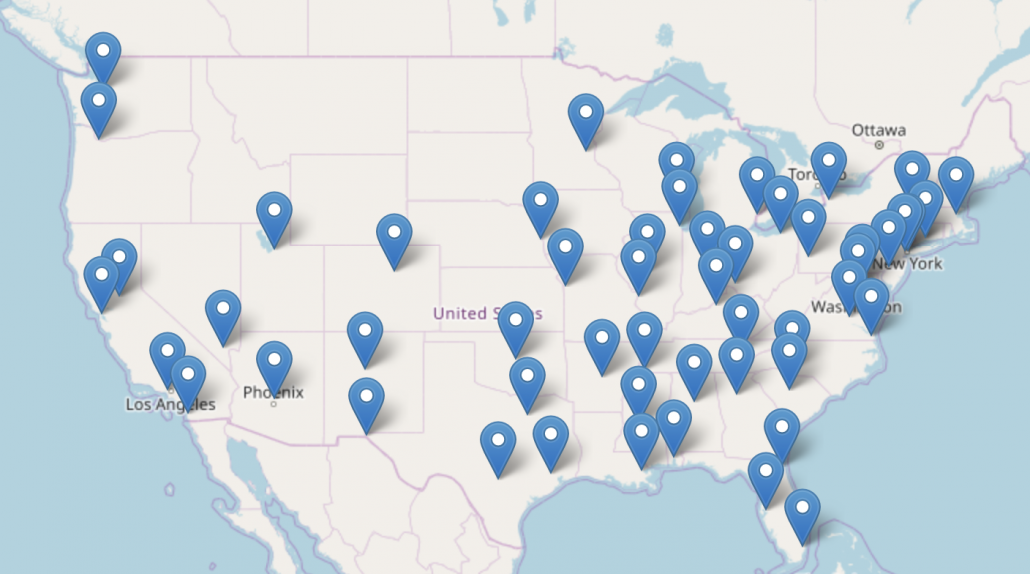

The FBI has 56 field offices. Some states (CA, TX, FL, NY, PA) have multiple FBI offices. Some offices cover multiple states.

In any given year, National Security Division’s Office of Intelligence only does FISA reviews in a fraction of the FBI offices — 25-30, per a recent court filing (FISA 702 reviews covered a smaller number of offices during the early years of the 5-year period, but it’s unclear whether NSD does the reviews at the same time). A James Boasberg opinion on 702 reauthorization from last year confirmed that, “OI understandably devotes more resources to offices that use FISA authorities more frequently.” That would presumably include DC, NY, and LA (all of which are big enough to be led by an Assistant Director). Cities with large numbers of Chinese-Americans (like SF) or Muslims (like Minneapolis and Detroit) likely do disproportionately more FISA than other large city offices, and I assume offices in TX and FL do a lot as well.

Prong One: Reviewing Woods Files

DOJ IG described that one prong of their review — their own review of Woods Files — involved visiting those 8 field offices “of varying sizes” and reviewing “judgmentally selected sample” of 29 applications to review.

over the past 2 months, we visited 8 FBI field offices of varying sizes and reviewed a judgmentally selected sample of 29 applications relating to U.S. Persons and involving both counterintelligence and counterterrorism investigations. This sample was selected from a dataset provided by the FBI that contained more than 700 applications relating to U.S. Persons submitted by those 8 field offices over a 5-year period.

Between them, those 8 field offices submitted 700 applications in the 5-year period studied, which says that even with some smaller offices included, the field offices still submitted almost half of the US person applications in the period (meaning DOJ IG likely included at least a few of the biggest offices).

This review is ongoing. But thus far, assuming my 1,500 estimate is fair, DOJ IG reviewed around 2% of the applications submitted by the FBI, or 4% of those submitted by these offices. By definition, those 29 files could not have included an application from each office for each year.

For each of these 29 applications, DOJ IG reviewed the Woods File associated with the application to see if there was, as intended, back-up for each of the factual claims in the application; that’s all they’ve done so far. This prong of the review was a strictly paperwork review: DOJ IG did not review whether the claims in the application could be backed up elsewhere, or if there were things in the case file targeting a person that should have been included in the application (which was actually the far bigger problem in the Carter Page applications).

[I]nitial review of these applications has consisted solely of determining whether the contents of the FBI’s Woods File supported statements of fact in the associated FISA application; our review did not seek to determine whether support existed elsewhere for the factual assertion in the FISA application (such as in the case file), or if relevant information had been omitted from the application.

But they didn’t have to keep reviewing to conclude that Woods Files are not functioning like they’re supposed to. Not only was there not a Woods File for 4 of the applications, but the remaining 25 all had problems.

(1) we could not review original Woods Files for 4 of the 29 selected FISA applications because the FBI has not been able to locate them and, in 3 of these instances, did not know if they ever existed; (2) our testing of FISA applications to the associated Woods Files identified apparent errors or inadequately supported facts in all of the 25 applications we reviewed, and interviews to date with available agents or supervisors in field offices generally have confirmed the issues we identified;

[snip]

[F]or all 25 FISA applications with Woods Files that we have reviewed to date, we identified facts stated in the FISA application that were: (a) not supported by any documentation in the Woods File, (b) not clearly corroborated by the supporting documentation in the Woods File, or (c) inconsistent with the supporting documentation in the Woods File. While our review of these issues and follow-up with case agents is still ongoing—and we have not made materiality judgments for these or other errors or concerns we identified—at this time we have identified an average of about 20 issues per application reviewed, with a high of approximately 65 issues in one application and less than 5 issues in another application.

By comparison, DOJ IG found just 8 Woods File errors in the first Carter Page application and 16 in last two, most problematic, renewals (see PDF 460-465). So the applications DOJ IG reviewed were, on average, worse than the Page application with respect to the Woods compliance.

These applications also didn’t all have the required paperwork from an informant’s handling agent — though in some cases, the agent was the same.

About half of the applications we reviewed contained facts attributed to CHSs, and for many of them we found that the Woods File lacked documentation attesting to these two requirements. For some of these applications, the case agent preparing the FISA application was also the handling agent of the CHS referenced in the application, and therefore would have been familiar with the information in CHS files.

It’s actually somewhat notable that just half of this very small sample of applications included information from an informant. And only some of these files were lacking the required paperwork for informants. That suggests, to the degree that the FISA application might hide problems with informants that otherwise might have been found in a criminal warrant affidavit (though even there, FBI has a lot of ways to protect these details), that may not be as big of a problem as defense attorneys have suspected (though that’s an area where I’d expect bigger problems on the CT side than the CI one).

The findings on the third problem identified in the Carter Page applications — that the Woods File did not get a fresh review with each application — are less definitive.

based on the results of our review of two renewal files, as well as our discussions with FBI agents, it appears that the FBI is not consistently re-verifying the original statements of fact within renewal applications. In one instance, we observed that errors or unsupported information in the statements of fact that we identified in the initial application had been carried over to each of the renewal applications. In other instances, we were told by the case agents who prepared the renewal applications that they only verified newly added statements of fact in renewal applications because they had already verified the original statements of fact when submitting the initial application.

This could represent as few as 3 of the 25 files for which there were Woods Files.

In any case, the larger point seems to be the more important one: the FBI has not been using Woods Files like they’re supposed to, making sure that the paperwork to back up any claim made in a FISA application actually reflects the underlying documentation and thereby making sure the claims they make to the FISC are valid.

Presiding FISA Judge James Boasberg issued an order today, requiring the government to figure out whether any of the problems identified in this review were material, with an emphasis on the 4 applications for which there was no Woods File.

Reviewing Accuracy Reviews

As noted, the FBI has not been using Woods Files like they’re intended to be used. But neither is DOJ’s National Security Division.

The other part of DOJ IG’s audit involved reviewing the Accuracy Reviews done by the FBI and NSD as part of the existing FISA oversight process.

There are two kinds of Accuracy Reviews done as part of FISA oversight. First, the FBI requires that lawyers in its field offices review at least one application a year.

FBI requires its Chief Division Counsel (CDC) in each FBI field office to perform each year an accuracy review of at least one FISA application from that field office.

As noted below, these are sent to FBI OGC. NSD’s Office of Intelligence doesn’t get them.

In addition, NSD OI does their own reviews for a subset of offices.

Similarly, NSD’s Office of Intelligence (OI) conducts its own accuracy review each year of at least 1 FISA application originating from each of approximately 25 to 30 different FBI field offices.

Remember there are 56 field offices and roughly 300 US person applications. So in practice, IO could review as few as 8% of the applications in a given year (though it’s probably more than that).

Here’s how DOJ described the OI reviews to FISC in December.

OI’s Oversight Section conducts oversight reviews at approximately 25-30 FBI field offices annually. During those reviews, OI assesses compliance with Court-approved minimization and querying procedures, as well as the Court orders. Pursuant to the 2009 Memorandum, OI also conducts accuracy reviews of a subset of cases as part of these oversight reviews to ensure compliance with the Woods Procedures and to ensure the accuracy of the facts in the applicable FISA application. 5 OI may conduct more than one accuracy review at a particular field office, depending on the number of FISA applications submitted by the office and factors such as whether there are identified cases where errors have previously been reported or where there is potential for use of FISA information in a criminal prosecution. OI has also, as a matter of general practice, conducted accuracy reviews of FISA applications for which the FBI has requested affirmative use of FISA-obtained or -derived information in a proceeding against an aggrieved person. See 50U.S.C. §§ 1806(c), 1825(d).

(U) During these reviews, OI attorneys verify that every factual statement in the categories of review described in footnote 5 is supported by a copy of the most authoritative document that exists or, in enumerated exceptions, by an appropriate alternate document. With regard specifically to human source reporting included in an application, the 2009 Memorandum requires that the accuracy sub-file include the reporting that is referenced in the application and further requires that the FBI must provide the reviewing attorney with redacted documentation from the confidential human source sub-file substantiating all factual assertions regarding the source’s reliability and background. 6

5 (U) OI’s accuracy reviews cover four areas: (1) facts establishing probable cause to believe that the target is a foreign power or an agent of a foreign power; (2) the fact and manner of FBI’s verification that the target uses or is about to use each targeted facility and that property subject to search is or is about to be owned, used, possessed by, or in transit to or from the target; (3) the basis for the asserted U.S. person status of the target(s) and the means of verification; and (4) the factual accuracy of the related criminal matters section, such as types of criminal investigative techniques used (e.g., subpoenas) and dates of pertinent actions in the criminal case. See 2009 Memorandum at 3.

6 (U) If production of redacted documents from the confidential human source sub-file would be unduly burdensome, compromise the identity of the source, or otherwise violate the Attorney General Guidelines for Confidential Human Sources or the FBI’s Confidential Human Source Manual, FBI personnel may request that the attorney use a human source sub-file request form. Upon receipt of that form, the relevant FBI confidential human source coordinator will verify the accuracy of the source’s reliability and background that was used in the application, and transmit the results of that review to the reviewing or attorney.

So in December, DOJ claimed that these reviews served to “ensure compliance with the Woods Procedures and to ensure the accuracy of the facts in the applicable FISA application.” They claimed that “OI attorneys verify that every factual statement in the categories of review described in footnote 5” — pertaining to 1) facts establishing probable cause 2) the target actually uses the targeted facilities 3) the target is a US person and 4) the criminal investigative techniques are accurately described — are “supported by a copy of the most authoritative document that exists or, in enumerated exceptions, by an appropriate alternate document.” In theory, the easiest way to verify bullet point 1 (the case for probable cause) would be for the OI lawyers to check whether the Woods Files were complete.

Before I get into results, a word about the numbers.

Altogether, DOJ IG reviewed 34 FBI CDC and NSD OI reports and those reports covered 42 US person FISA applications.

Specifically, in addition to interviewing FBI and NSD officials, we reviewed 34 FBI and NSD accuracy review reports covering the period from October 2014 to September 2019—which originated from the 8 field offices we have visited to date and addressed a total of 42 U.S. Person FISA applications, only one of which was also included among the 29 FISA applications that we reviewed.

These numbers are bit confusing. For starters, the base number of accuracy reports, 34, is less than 40 (what it would be if there were a review for all 8 field offices for each of 5 years, which is supposed to be mandated for each FBI office). DOJ IG did not review one application per year per FBI office. I asked DOJ IG why that was; they said only “there may be many reasons why this is the case,” emphasizing multiple times that this audit is in its earliest phases (I’ve got requests for comment in with both NSD and FBI). Some of those many reasons might be:

- Smaller offices reviewed don’t submit a FISA application every year, so for some offices there was none to review

- OI doesn’t review most FBI offices every year, so for less frequently reviewed offices, there won’t be a review every year (but there should be an FBI one if the office did any FISA applications)

- DOJ IG was only interested in US person FISA applications; some of the ones that FBI and OI reviewed would likely not target US persons

- Only applications for which FISA coverage had ended were reviewed; for the later applications, FISA coverage might be ongoing and therefore excluded from the DOJ IG review

- DOJ IG may not have finished its review of all these Accuracy Reviews reviews yet, so didn’t include them in the MAM

Additionally, the references to this part of review seems to suggest that the NSD reviews the same FISA application that each FBI field office reviews each year, as well as any problematic ones or ones being used in a prosecution, though that’s something I’m trying to get clarity on. Likewise, I’m trying to figure out whether FBI and OI similarly try to pick a “judgmentally selected sample” to ensure both the counterterrorism and counterintelligence functions are reviewed.

One detail makes this process a really bad measure of Woods File compliance (which is different from whether they measure the accuracy of the application effectively). Before any of these reviews happen, the field offices are told which applications will be reviewed, which gives the case agents a chance to pull together the documentary support for the application.

Thus, prior to the FBI CDC or NSD OI review, field offices are given advance notification of which FISA application(s) will be reviewed and are expected to compile documentary evidence to support the relevant FISA.

If the Woods Procedures were being followed, it should never be the case that the FBI needs to compile documentary evidence before the review; the entire point of it is it ensure the documentary evidence is in the file before any application gets submitted. Once you discover that all the FBI and OI reviews get advance notice, you’re not really reviewing Woods Procedures, it seems to me, you’re reviewing paperwork accuracy.

Nevertheless, even with the advance notice, the 93% of the 42 applications DOJ IG reviewed included problems.

[T]hese oversight mechanisms routinely identified deficiencies in documentation supporting FISA applications similar to those that, as described in more detail below, we have observed during our audit to date. Although reports related to 3 of the 42 FISA applications did not identify any deficiencies, the reports covering the remaining 39 applications identified a total of about 390 issues, including unverified, inaccurate, or inadequately supported facts, as well as typographical errors. At this stage in our audit, we have not yet reviewed these oversight reports in detail.

Keep in mind, OI is reviewing for four things — whether there’s paperwork present to support that the application shows 1) facts establishing probable cause 2) the target actually uses the targeted facilities 3) the target is a US person (or, for applications targeting under the lower foreign power standard, that the target is not a US person, but that shouldn’t be relevant here) and 4) the criminal investigative techniques used already are accurately described. The second bullet point is actually at least as important as the probable cause, because if the wrong person is wiretapped, then a completely innocent person ends up compromised. That’s the kind of thing where typographical errors (say, transposing 2 digits in a phone number) have had serious ramifications in the past.

The lack of clarity regarding numbers makes one other point unclear. The memo setting up this process envisions NSD’s involvement in assessing whether problems with FISA applications are material. But in practice, the FBI doesn’t consult with them. And in the set of applications that DOJ IG Reviewed (again, it’s unclear whether OI reviewed all the FBI files, along with a select few more, or not), FBI found more problems than OI did, 250 as compared to 140 (for a total of 390 problems).

The 2009 joint FBI-NSD policy memorandum states that “OI determines, in consultation with the FBI, whether a misstatement or omission of fact identified during an accuracy review is material.” The 34 reports that we reviewed indicate that none of the approximately 390 identified issues were deemed to be material. However, we were told by NSD OI personnel that the FBI had not asked NSD OI to weigh in on materiality determinations nor had NSD OI formally received FBI CDC accuracy review results, which accounted for about 250 of the total issues in the reports we reviewed.

[snip]

FBI CDC and NSD OI accuracy review reports had not been used in a comprehensive, strategic fashion by FBI Headquarters to assess the performance of individuals involved in and accountable for FISA applications, to identify trends in results of the reviews, or to contribute to an evaluation of the efficacy of quality assurance mechanisms intended to ensure that FISA applications were “scrupulously accurate.” That is, the accuracy reviews were not being used by the FBI as a tool to help assess the FBI’s compliance with its Woods Procedures.

This is one of the complaints and recommendations in the MAM: it complains that the FBI reviews are basically going into a file somewhere, without a lessons learned process. It recommends that change. It also recommends that OSD get FBI’s reports, so they can integrate them into their own “trends reports” that they do based on their own reviews.

DOJ IG describes its finding that these results aren’t being used in better fashion.

(4) FBI and NSD officials we interviewed indicated to us that there were no efforts by the FBI to use existing FBI and NSD oversight mechanisms to perform comprehensive, strategic assessments of the efficacy of the Woods Procedures or FISA accuracy, to include identifying the need for enhancements to training and improvements in the process, or increased accountability measures.

At least given their description, however, I think they’ve found something else. They’ve confirmed that — contrary to DOJ’s description to FISC that,

OI also conducts accuracy reviews of a subset of cases as part of these oversight reviews to ensure compliance with the Woods Procedures and to ensure the accuracy of the facts in the applicable FISA application.

OI is actually only doing the latter part, measuring the accuracy of the facts in an applicable FISA application. To check the accuracy of the Woods Files, they should with no notice obtain a subset of them, as DOJ IG just did, and see whether the claims in the report are documented in the Woods File, and only after that do their onsite reviews (with notice, to see if there was documentation somewhere that had not been included in the file). That might actually be a better way of identifying where there might be other kinds of problems with the application.

With regards to the lessons learned problem, there seems like an obvious solution to this: Congress mandates that DOJ complete semiannual reviews of 702 practices (which includes reviews of NSA and CIA practices, as well as those of FBI), and they include precisely this kind of trend analysis. Even in spite of their heavy redaction in public form, I’ve even been able to identify problems with 702 and related authorities in the same time frame as NSA was doing so. There’s no reason that semiannual reports couldn’t be expanded (or replicated) to include probable cause targeting. At the very least it’d be a way to force OI and FBI to have this lessons learned discussion. Republican members of Congress have claimed that more oversight should be shifted to Congress (not a very good idea given that no one in Congress seemed to be conducting the close read that I had been), and this is an easy way to play a more active role.

DOJ IG has not reviewed the most important things yet

The MAM is explicit that it has not reviewed the import of the errors it found.

[W]e have not made judgments about whether the errors or concerns we identified were material. Also, we do not speculate as to whether the potential errors would have influenced the decision to file the application or the FISC’s decision to approve the FISA application. In addition, our review was limited to assessing the FBI’s execution of its Woods Procedures, which are not focused on affirming the completeness of the information in FISA applications.

Nor has it reviewed FBI’s own decisions regarding the 290 errors they found in their own reviews to determine if the FBI’s judgment that they were not material was valid. If it compared its results for the one application that FBI and/or OI also reviewed, it doesn’t say so explicitly (which would seem a really important measure about the integrity of the standard reviews).

And while it’s significant that there are so many errors, regardless of the review, it still doesn’t address what the Carter Page case said was the far more important issue: what got left out. Of the 8 to 18 Woods Files errors in the Carter Page investigation, for example, just one got to the core of the problem with the application, that Page was making denials, denials that — before later applications were submitted — the FBI had reason to know were correct (another of the Woods File errors might have raised questions about Steele, but did not go to the heart of the problems with his reporting). The other problems had to do with paperwork, not veracity. And none of the Woods File problems related to CIA’s contact approval of Page for some but not all of his willful sharing of non-public information with known Russian intelligence officers.

DOJ IG says it will conduct further analysis of the problems it has thus far found.

In connection with our ongoing audit, the OIG will conduct further analysis of the deficiencies identified in our work to date and of FBI FISA renewals. In addition, we are expanding the audit’s objective to also include FISA application accuracy efforts performed within NSD. Consistent with the OIG’s usual practices, we will keep the Department and the FBI appropriately apprised of the scope of our audit, and we will prepare a formal report at the conclusion of our work.

But it’s not yet clear that this will include picking a subset of the files already reviewed to do the kind of deep dive that was done with Carter Page.

Further, at this point, DOJ IG seems not to be seeing one of the more obvious conclusions. As explained above, it recommends that the FBI and NSD use their accuracy reviews better to better do lessons learned.

We recommend that the FBI institute a requirement that it, in coordination with NSD, systematically and regularly examine the results of past and future accuracy reviews to identify patterns or trends in identified errors so that the FBI can enhance training to improve agents’ performance in completing the Woods Procedures, or improve policies to help ensure the accuracy of FISA applications.

But it specifically speaks in terms of improving performance with the Woods Procedures.

If the Woods Procedures are meant to be a tool, it would be necessary to conduct no-notice reviews of the files. Otherwise, you’re not reviewing the Woods Procedures. That would need to be a recommendation.

But it seems to be possible if not likely that fixing the problems IDed back before 2000 with a paperwork requirement that doesn’t go to the core of the issue hasn’t worked (and, as described, has never been used as a key measure for the existing OI reviews), then it seems other solutions are necessary — including that criminal defendants get some kind of review. Though even that would be inadequate to the task, given that before DOJ makes the decision to permit FISA materials to be used in a prosecution, they review whether the files would sustain a judge’s review first.

The goal here is not to placate FISC, nor is it to check some boxes as part of the application process. It’s to ensure that absent the threat of review by a defense attorney, the benefits (which already have serious limits) of adversarial review are achieved via other means. And there’s good reason to believe that absent more significant changes in the oversight process, the Woods Procedures are never going to achieve that result.

The Michael Atkinson conspiracy theory

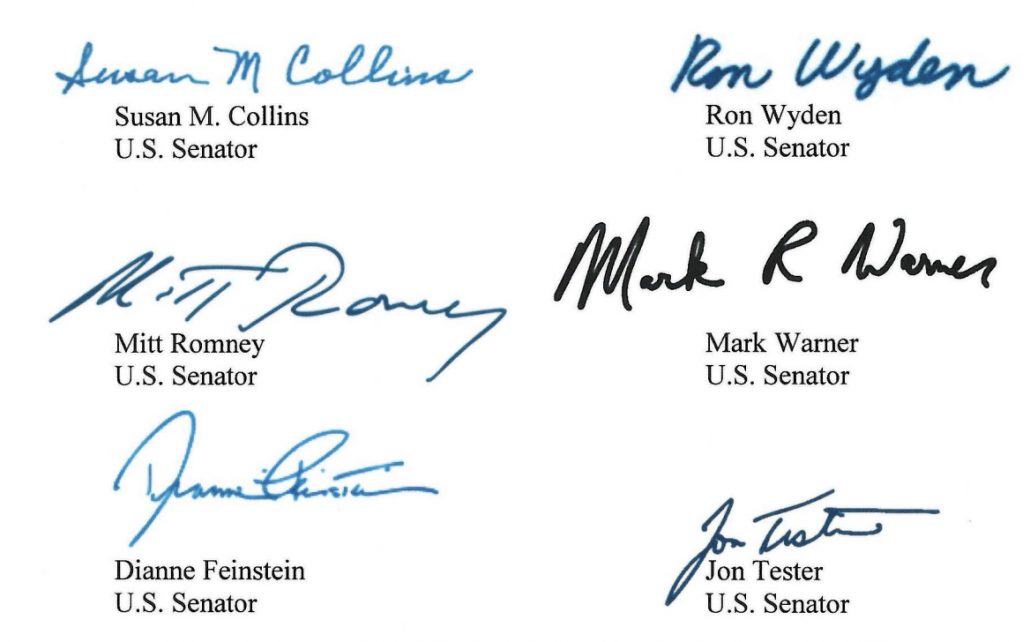

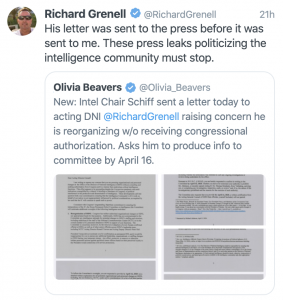

As I was already writing this, it became clear that the frothy right was using this report, released on Tuesday, to provide a non-corrupt excuse for Trump’s firing of Intelligence Community Inspector General Michael Atkinson late on Friday night.

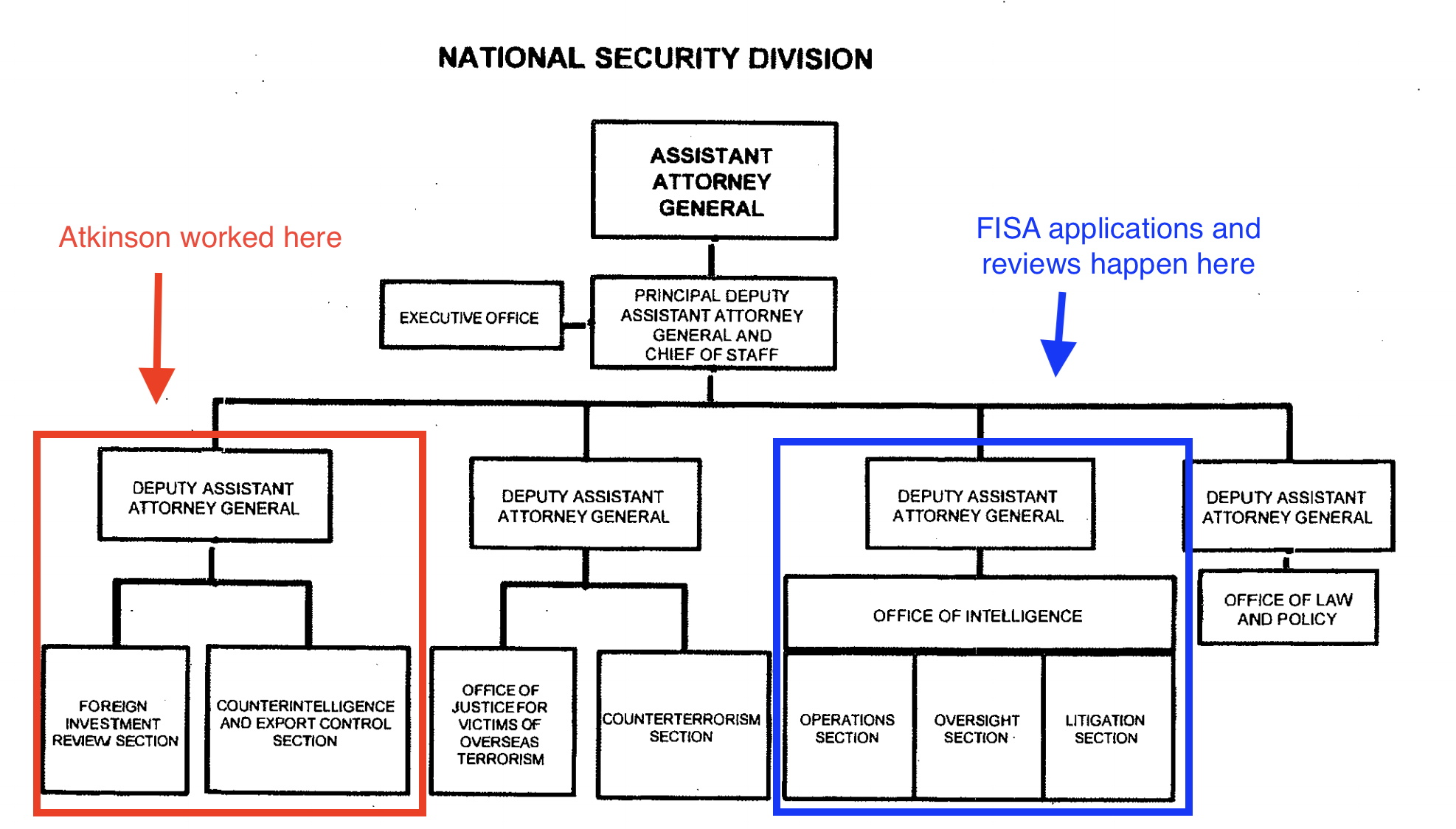

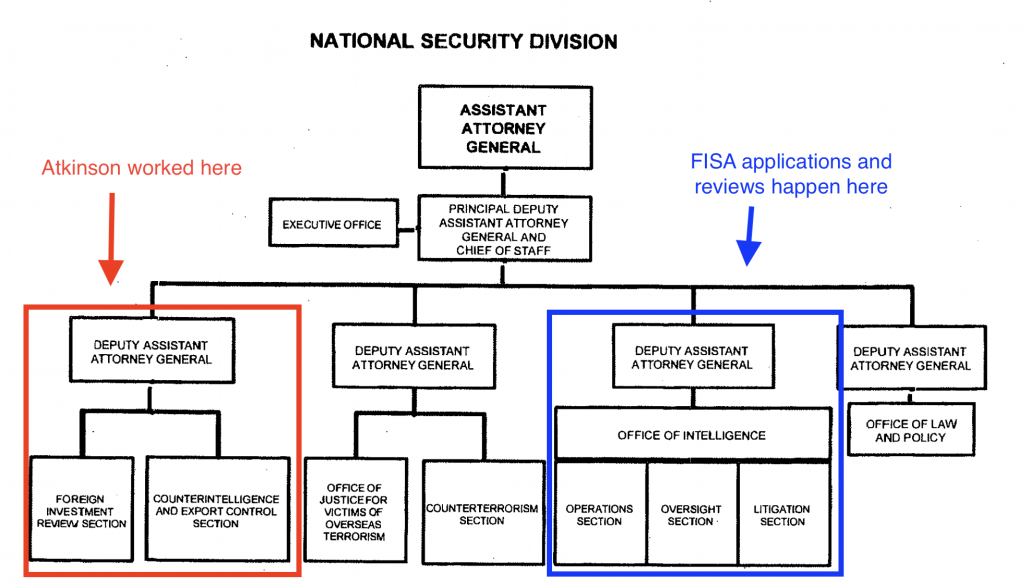

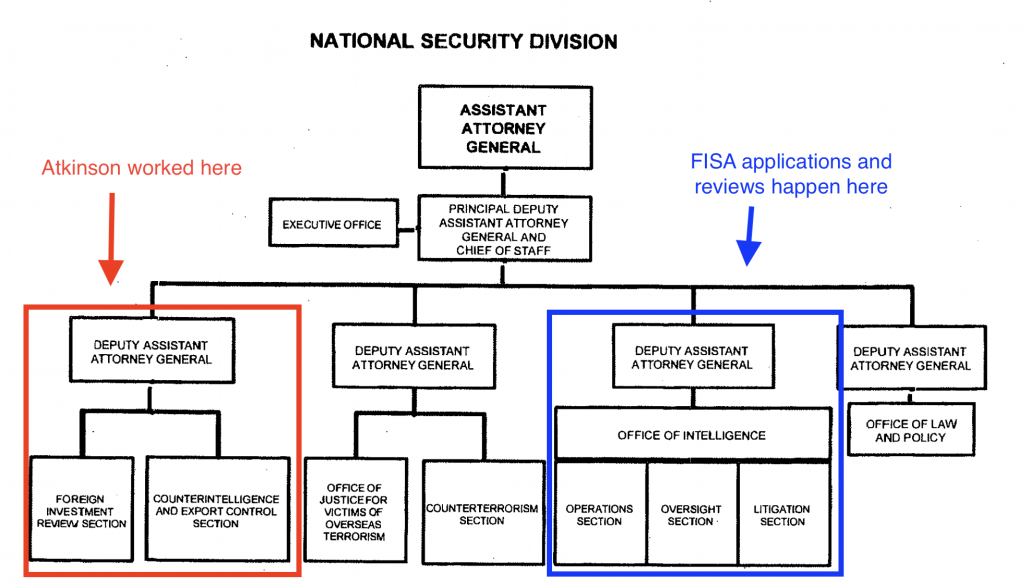

The basis for such a claim is not entirely clear to me. Frothers in my Twitter timeline at first seemed to confuse Atkinson with DOJ’s IG, Michael Horowitz, or believed that the ICIG had a central role in FISA. Then they seized on the fact that, for the two years before he became ICIG, Atkinson was at National Security Division, which both oversees some cases likely to have a FISA component and oversees the submission of applications and then conducts the oversight reviews.

Atkinson’s confirmation materials provide some exactitude for what he did at DOJ when:

September 2002 to March 2006: Trial Attorney for DOJ’s Fraud Section

March 2006 to March 2016: AUSA in DC USAO working on Fraud (including in oversight positions)

March 2016 to June 2016: Acting DAAG, National Asset Protection at NSD

July 2016 to May 2018: Senior Counsel to AAG for NSD

There would be little imaginable reason for a fraud prosecutor, as Atkinson was for the majority of his DOJ career, to use FISA (two of the highest profile cases he worked on were the prosecution of Democratic Congressmen William Jefferson and Jesse Jackson Jr), though he said he worked on some espionage, sanctions, and FARA cases. As Acting DAAG, he worked in a different part of NSD than the unit that handles FISA applications and oversight.

As he described it in his confirmation materials, he would have been a consumer of FISA information, but not the person doing the reviews.

As Senior Counsel to the AAG (serving under John Carlin, Mary McCord, Dana Boente, and John Demers), he might have visibility into review processes on FISAs, though at that level, managers assumed the Woods Procedure worked as required (meaning, Atkinson would not have known of these problems).

In his confirmation materials, however, Atkinson suggested he spent far more time as Senior Counsel overseeing the response to unauthorized disclosures, which likely still included Snowden when he started in 2016, added Shadow Brokers that year, and would have focused closely on Vault 7 in 2017 and 2018.

My experience in helping to coordinate the responses to unauthorized disclosures while serving as the Senior Counsel to the Assistant Attorney General, U.S. Department of Justice, National Security Division (NSD), should assist me in serving effectively as the IC IG. As part of this position, I have assisted in coordinating the Department’s efforts to investigate and prosecute unauthorized disclosures across the IC enterprise. This experience has reinforced for me the important role that fair, impartial, and effective whistleblower protection processes play in maximizing the IC’s effectiveness and minimizing the risks of unauthorized disclosures and harm to our national security. As part of this experience, I have also been a consumer and user of intelligence from multiple intelligence sources, and I have seen first-hand the benefits to our country when there is a unity of effort by the Intelligence Community to address national security needs.

For Vault 7, at least, the investigation into Joshua Schulte — who was always the prime suspect — used criminal process from the very start (though it’s possible that the increased surveillance of Julian Assange involved FISA). And while there are less spectacular cases of unauthorized disclosure that might involve some nexus with a foreign country, raising FISA issues, many of these leaks cases were criminal cases, seemingly not reliant on FISA. Which would mean some of the most sensitive cases Atkinson worked on didn’t involve FISA.

Though the frothy right may think Atkinson had a central role because the title of the person at FBI field offices who must conduct a review is “Chief [Division] Counsel,” and they confused both the agency and the location.

In any case, there’s one more piece missing from this: while I happen to think DOJ IG has not focused closely enough on what NSD should be doing in its oversight role, thus far, DOJ IG has not investigated it. And so there’s actually no allegation of wrong-doing from anyone at NSD in either of these two reports, not even the NSD people who actually work on FISA. On the contrary, DOJ IG simply describes OI doing reviews where they identified problems and wrote them up. Yes, OI likely should have been more involved in determining whether the errors FBI found were material. Given that Boasberg has mandated materiality reviews of the 29 files reviewed by DOJ IG, now would be a good time to implement that practice.

Still, compliance or not with Woods Files remains a distraction from a deeper review of whether these files included all pertinent information. And if FISA is going to remain viable, that’s the examination that needs to happen.