Last week, I wrote this post arguing that Mike Flynn’s 302 (FBI interview report) shows what Flynn was hiding when he lied to the FBI: In addition to his most fundamental lie — that he and Sergei Kislyak had talked about Russia moderating its response to new Obama sanctions, Flynn lied about his coordination with KT McFarland, who was with Trump at Mar-a-Lago.

Since people are still wondering why Flynn lied, I thought I’d write it up to make it even more plain. This post relies on these sources:

As Flynn’s Statement of the Offense lays out, Obama signed the Executive Order imposing new sanctions on December 28, 2016.

On or about December 28, 2016, then-President Barack Obama signed Executive Order 13757, which was to take effect the following day. The executive order announced sanctions against Russia in response to that government’s actions intended to interfere with the 2016 presidential election (“U.S. Sanctions”).

Flynn admitted that Kislyak contacted him the day Obama imposed the sanctions.

On or about December 28, 2016, the Russian Ambassador contacted FLYNN.

Flynn told the FBI that was a text that, because of poor connectivity in Dominican Republic, he didn’t see for a day. (I suspect this is also a lie, but it is possible.)

Shortly after Christmas, 2016, FLYNN took a vacation to the Dominican Republic with his wife. On December 28th, KISLYAK sent FLYNN a text stating, “Can you call me?”

Sometime in the day after Obama imposed the sanctions, Lisa Monaco gave her successor, Tom Bossert, a heads up about how angry the Russians were, making it clear the Obama Administration had formally contacted them.

Obama administration officials were expecting a “bellicose” response to the expulsions and sanctions, according to the email exchange between Ms. McFarland and Mr. Bossert. Lisa Monaco, Mr. Obama’s homeland security adviser, had told Mr. Bossert that “the Russians have already responded with strong threats, promising to retaliate,” according to the emails.

That suggests that the Obama Administration formally alerted the Russians before Kislyak’s text and alerted the Trump Transition not long after. That is, the Flynn-Kislyak contacts occurred after Obama had informed both sides, if not Flynn directly.

In spite of that formal notification, Flynn attributed any delay in responding to Kislyak to Dominican Republic’s poor cell phone reception. He claims (probably assuming the only communications the FBI would ever review would be Kislyak’s communications) that he saw the text on the 29th, took a bit of time, then called the Russian Ambassador.

FLYNN noted cellular reception was poor and he was not checking his phone regularly, and consequently did not see the text until approximately 24 hours later. Upon seeing the text, FLYNN responded that he would call in 15-20 minutes, and he and KISLYAK subsequently spoke.

What Flynn didn’t tell the FBI is that, per his allocution, he spoke with KT McFarland immediately before his call with Kislyak (importantly, this is true whether he really didn’t find out until the 29th or if there was a longer conversation with McFarland).

On or about December 29, 2016, FLYNN called a senior official of the Presidential Transition Team (“PTT official”), who was with other senior ·members of the Presidential Transition Team at the Mar-a-Lago resort in Palm Beach, Florida, to discuss what, if anything, to communicate to the Russian Ambassador about the U.S. Sanctions. On that call, FLYNN and the PTT official discussed the U.S. Sanctions, including the potential impact of those sanctions on the incoming administration’s foreign policy goals. The PTT official and FLYNN also discussed that the members of the Presidential Transition Team at Mar-a-Lago did not want Russia to escalate the situation.

Immediately after his phone call with the PTT official, FLYNN called the Russian Ambassador and requested that Russia not escalate the situation and only respond to the U.S. Sanctions in a reciprocal manner.

The account of the timing of discussions both at Mar-a-Lago and with advisors who were dispersed across the globe in the NYT story is vague. Though NYT makes it clear that one email, at least, described the Flynn call with Kislyak prospectively.

As part of the outreach, Ms. McFarland wrote, Mr. Flynn would be speaking with the Russian ambassador, Mr. Kislyak, hours after Mr. Obama’s sanctions were announced.

One of those emails, importantly, included the following talking points.

Obama is doing three things politically:

- discrediting Trump’s victory by saying it was due to Russian interference

- lure trump into trap of saying something today that casts doubt on report on Russia’s culpability and then next week release report that catches Russia red handed

- box trump in diplomatically with Russia. If there is a tit-for-tat escalation trump will have difficulty improving relations with Russia which has just thrown USA election to him. [my emphasis]

Per the NYT, that email appears to have been forwarded to — among others — Flynn.

Mr. Bossert forwarded Ms. McFarland’s Dec. 29 email exchange about the sanctions to six other Trump advisers, including Mr. Flynn; Reince Priebus, who had been named as chief of staff; Stephen K. Bannon, the senior strategist; and Sean Spicer, who would become the press secretary.

One thing makes it more likely that Flynn received McFarland’s email (or at least equivalent talking points via phone), and received it before he returned the call to Kislyak. When the Agents moved to the stage of the interview where — per Peter Strzok’s later description — “if Flynn said he did not remember something they knew he said, they would use the exact words Flynn used,” they quoted that “tit-for-tat” language.

The interviewing agents asked FLYNN if he recalled any conversation with KISLYAK in which the expulsions were discussed, where FLYNN might have encouraged KISLYAK not to escalate the situation, to keep the Russian response reciprocal, or not to engage in a “tit-for-tat.” FLYNN responded, “Not really. I don’t remember. It wasn’t, “Don’t do anything.” [my emphasis]

So whether Flynn saw this language in an email first, it seems clear he spoke to McFarland — who was coordinating all this from Mar-a-Lago, where Trump was — before he spoke with Kislyak. And that’s important, because Flynn claimed he had no idea that the US had expelled a bunch of Russian diplomats “until it was in the media.”

The U.S. Government’s response was a total surprise to FLYNN. FLYNN did not know about the Persona-Non-Grata (PNG) action until it was in the media. KISLYAK and FLYNN were starting off on a good footing and FLYNN was looking forward to the relationship. With regard to the scope of the Russians who were expelled, FLYNN said he did not understand it. FLYNN stated he could understand one PNG, but not thirty-five.

It’s possible that Flynn didn’t learn about the expulsions until Obama’s press releases on the 29th, if he didn’t check with McFarland before that. Except he also claimed the FBI that he didn’t have access to TV news in DR.

FLYNN noted he was not aware of the then-upcoming actions as he did not have access to television news in the Dominican Republic and his government BlackBerry was not working.

In context in his 302, though, that seems to be offered as a substantiating detail to support his claim that he didn’t know about the expulsions before he spoke with Kislyak — or, indeed, the even crazier claim that Kislyak didn’t raise it on that call, regardless of what Flynn knew going into the call.

The interviewing agents asked FLYNN is he recalled any conversation with KISLYAK surrounding the expulsion of Russian diplomats or closing of Russian properties in response to Russian hacking activities surrounding the election. FLYNN stated that he did not. FLYNN reiterated his conversation was about [Astana peace conference] described earlier.

Consider how ridiculous this lie is: Flynn wanted the FBI to believe that, having asked Flynn to contact him after Russia was informed of Obama’s sanctions, Kislyak didn’t even mention the sanctions to him.

That’s obvious nonsense. But it was a necessary to hide two things. First, that he had spoken with Kislyak about sanctions — which is what the focus has been on until now.

But claiming that he hadn’t heard about the expulsions before he called Kislyak also served to hide an equally critical detail: Flynn had not only heard of the sanctions (if he hadn’t already heard) from his deputy, KT McFarland, who was at Mar-a-Lago with Trump, but she and he and a number of other people had coordinated what he would say to Kislyak before the call. And they did do based off the belief that Obama’s actions against Russia were all a political set-up and not a sound response to Russia’s involvement in the election.

Flynn not only coordinated his messaging with McFarland, but he used language she offered, writing from Mar-a-Lago: “tit-for-tat.”

After Flynn pled guilty, McFarland spent some time cleaning up what she had told the FBI the previous summer (at a time when everyone seemed to believe their emails recording all this would never be reviewed by the FBI). According to WaPo’s coverage, McFarland,

walked back her previous denial that sanctions were discussed, saying a general statement Flynn had made to her that things were going to be okay could have been a reference to sanctions, these people said.

Flynn’s statement of the offense actually reflects two conversations that McFarland may have initially lied about — one on December 29, when Flynn reported back on his call with Kislyak, and another after his December 31 call with Kislyak, when Flynn reported back to “senior members of the Presidential Transition Team.”

Shortly after his phone call with the Russian Ambassador, FLYNN spoke with the PTT official to report on the substance of his call with the Russian Ambassador, including their discussion of the U.S. Sanctions.

On or about December 30, 2016, Russian President Vladimir Putin released a statement indicating that Russia would not take retaliatory measures in response to the U.S. Sanctions at that time.

On or about December 31, 2016, the Russian Ambassador called FLYNN and informed him that Russia had chosen not to retaliate in response to FL YNN’s request.

After his phone call with the Russian Ambassador, FLYNN spoke with senior members of the Presidential Transition Team about FL YNN’s conversations with the Russian Ambassador regarding the U.S. Sanctions and Russia’s decision not to escalate the situation.

It appears that Flynn tried to hide the entire existence of the call on December 31 (unless that’s why he claimed he had to keep calling back to Kislyak because of connectivity issues).

The interviewing agents asked FLYNN if he recalled any conversation with KISLYAK in which KISLYAK told him the Government of Russia had taken into account the incoming administration’s position about the expulsions, or where KISLYAK said the Government of Russia had responded, or chosen to modulate their response, in any way to the U.S.’s actions as a result of a request by the incoming administration. FLYNN stated it was possible that he talked to KISLYAK on the issue, but if he did, he did not remember doing so. FLYNN stated he was attempting to start a good relationship with KISLYAK and move forward. FLYNN remembered making four to five calls that day about this issue, but that the Dominican Republic was a difficult place to make a call as he kept having connectivity issues. FLYNN reflected and stated that he did not think he would have had a conversation with KISLYAK about the matter.

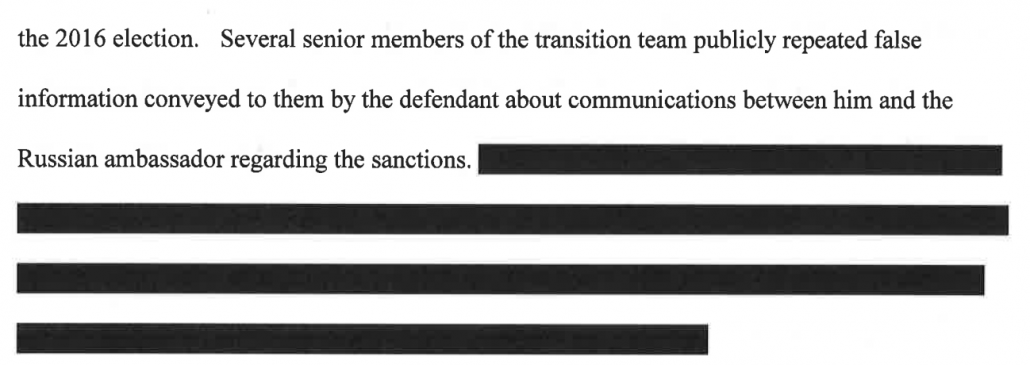

The point, however, is multiple people in the Transition lied about this back-and-forth involving people at Mar-a-Lago with Trump.

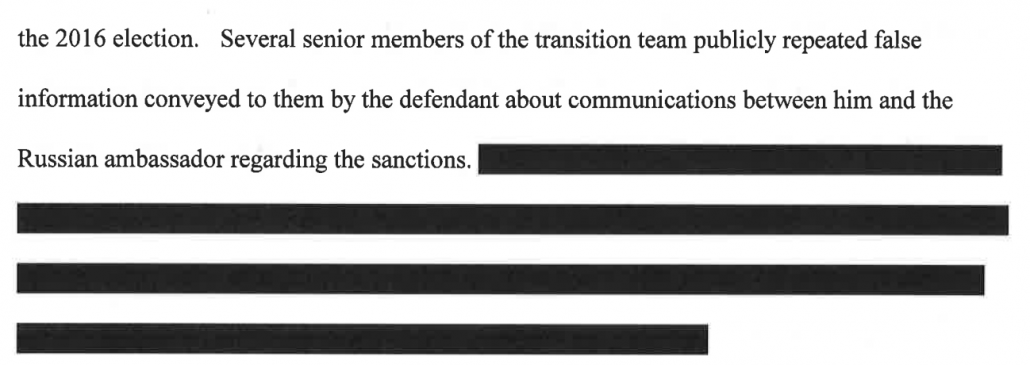

Their correction of those stories is probably one thing described in this redaction in Flynn’s sentencing addendum.

The fact that Flynn’s lies attempted to hide coordination with Mar-a-Lago and the Transition team generally is significant for several reasons.

First, it appears that at least KT McFarland and probably Sean Spicer were in on at least part of Flynn’s cover story. If that’s right, it would require more coordination than we’ve seen reported based on emails. It’s still unclear how much those who lied about Flynn’s conversations early in January 2017 — including Spicer but especially Mike Pence, who has not been named as receiving the emails among the Transition team — knew about Flynn’s conversations.

A perhaps more important detail, legally, is one that Ty Cobb — at the time, still working for Trump — tried to deny: at least one person in the Trump camp had assured the Obama Administration that they would not undercut Obama’s efforts to retaliate against Russia.

The Trump transition team ignored a pointed request from the Obama administration to avoid sending conflicting signals to foreign officials before the inauguration and to include State Department personnel when contacting them. Besides the Russian ambassador, Mr. Flynn, at the request of the president’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, contacted several other foreign officials to urge them to delay or block a United Nations resolution condemning Israel over its building of settlements.

Mr. Cobb said the Trump team had never agreed to avoid such interactions. But one former White House official has disputed that, telling Mr. Mueller’s investigators that Trump transition officials had agreed to honor the Obama administration’s request.

This puts a totally different spin on Susan Rice’s role in unmasking intercepts involving Trump transition officials exhorting the Russian Ambassador to blow off Obama’s sanctions and working with Mohammed bin Zayed al-Nahyan to keep a face-to-face meeting in NY secret (and probably also other intercepts assuring Bibi Netanyahu the Trump Transition would do all they could to undercut an Obama effort to punish Israeli settlements).

Rice would have unmasked those conversations having some reason to believe that the people involved in those discussions (Flynn and Kushner) were blowing off a Trump Transition commitment not to undercut Obama policy.

Such actions, then, would appear to go beyond a mere Logan Act violation. That is, Flynn and Kushner would have appeared to be pursuing their own foreign policy agenda, not just undercutting Obama’s policy, but also undercutting Trump’s (contested) agreement not to undercut Obama’s policies at least through the transition. And they would be doing so, by appearances, in pursuit of their own personal profit.

And those seeming instances of free-lancing would have accompanied Flynn’s request (in the days before it would be exposed that his Transition calls had been intercepted) to Rice to delay arming the Kurds, at a time when he was still legally hiding this relationship with Turkey.

Ultimately, we’re almost certainly going to learn all this was done with Trump’s explicit approval.

But because Flynn made such an effort to hide that his efforts to placate the Russians (and help the Turks and carry out undisclosed conversations with the Emirates and Israel) were done on the specific direction of Trump and Kushner, it would have looked like he was undermining both the Trump Administration and the interests of the United States.

It turns out he was only doing the latter.

As I disclosed in July, I provided information to the FBI on issues related to the Mueller investigation, so I’m going to include disclosure statements on Mueller investigation posts from here on out. I will include the disclosure whether or not the stuff I shared with the FBI pertains to the subject of the post.