The Gaslighter’s Psychiatrist: My Response to Dan Drezner

I wasn’t going to weigh in on the latest kerfuffle over Maggie Haberman. She wrote a book. It reveals things that would have been useful to know years ago. On several key points (such as what Trump did with the Strzok and Page texts), she seems unaware of related details that undermine her claims to exclusive smarts. The kerfuffle is not that interesting to me.

But Dan Drezner said two things in defense of her that are so fascinating, I couldn’t resist.

His most substantive defense of Maggie, bullet point 1, halfway into his post, is that most other politicians would not have remained standing after her stories.

Haberman is a pretty great reporter! Her stories on Trump were chock-full of tidbits that would have destroyed the standing of most other politicians. That Trump remained standing (sort of) after every one of her bombshell stories is a source of frustration to many, but Haberman is hardly to blame for this.

Drezner, who is a news-savvy political science professor with a column, not a journalist, spends much of the rest of his post lecturing about how journalism works.

For all the lecturing, he doesn’t note the most curious journalistic fact about Maggie’s book tour, at least to me: not that she delayed stories for the book, not necessarily that she’s telling stories she could have told in 2016 or 2018 or 2020 but did not, but that none of the teaser exclusives are being published at the NYT. The Atlantic, CNN, Axios, WaPo’s own Trump-whisperer — they’re the ones getting traffic from Maggie’s tidbits this week, not the NYT. After I started this, Joe Klein — better known as Joke Line!! — did a fawning review of the book in the NYT, but that’s not news or even, given that it was written by Joke Line, marginally reliable (though it may nevertheless be the most unintentionally insightful piece on the book).

When James Risen’s book about George Bush’s war on terror abuses was shunned by the NYT, it was a symptom of far more significant problems at the newspaper, problems that had to do with that outlet’s relationship to the Presidency (or perhaps Vice Presidency). Who knows whether that’s the case here. But it does raise questions about whether something is going on that explains NYT’s choice to let their star Trump-whisperer scoop them in virtually all the competing outlets — or whether they even had a choice in the matter.

Like I said, Drezner is a political science professor, so perhaps it was no surprise he missed what I find to be a more interesting curiosity about Maggie’s book blitz.

But he’s a political science professor, and so I would have welcomed some reflection about why he believes most other politicians, but not Trump, would have been destroyed by Maggie’s tidbits. Do Maggie’s strengths and weaknesses as a journalist offer any insight into Trump’s unique resilience? Is she a symptom of it? Or one of the causes? Those seem like utterly critical questions for political science professors as we try to stave off fascism in the United States.

As an access journalist, Maggie rises and falls with the subjects of her access. And this book — the payoff for years of access — is not just a story about Trump. It’s a story of her access, the transactional relationship it entailed, what Trump does with those he has selected to be witnesses to his power.

In the Atlantic excerpt of her book, Maggie famously described Trump likening her to his psychiatrist. She used that as a cue to close the piece with her wisdom about Trump — written in the first person but often, not always, quoting Trump’s direct speech, heightening both her own status as omniscient narrator but also the degree to which she is a manufactured character in her own book.

Then he turned to the two aides he had sitting in on our interview, gestured toward me with his hand, and said, “I love being with her; she’s like my psychiatrist.”

It was a meaningless line, almost certainly intended to flatter, the kind of thing he has said about the power of release he got from his Twitter feed or other interviews he has given over the years. The reality is that he treats everyone like they are his psychiatrists—reporters, government aides, and members of Congress, friends and pseudo-friends and rally attendees and White House staff and customers. All present a chance for him to vent or test reactions or gauge how his statements are playing or discover how he is feeling. He works things out in real time in front of all of us. Along the way, he reoriented an entire country to react to his moods and emotions.

I spent the four years of his presidency getting asked by people to decipher why he was doing what he was doing, but the truth is, ultimately, almost no one really knows him. Some know him better than others, but he is often simply, purely opaque, permitting people to read meaning and depth into every action, no matter how empty they might be.

We’re all like Maggie, omniscient narrator Maggie explains, all just bit players serving as a sounding board to witness him ramble for 20 minutes, all the while cutting us off so he can find the precise word he wants. But maybe not. In the next paragraph, first person Maggie reminds us that everyone else asks her, the sounding board Trump likens to his shrink, to “decipher” him. And this woman who stages herself as a participant in three interviews in this piece, concludes not that she’s got no insight, but that he’s simply opaque, something that we — including Maggie the character portrayed interviewing Trump — project our interpretations of depth onto.

Maggie sells herself as the false promise that you might get to know Trump through his quoted lies and not through his means or his deeds, not through understanding how those lies and the way they are circulated wielded power.

And that, Drezner observes, didn’t end up sticking to Trump the way it would other politicians. That seems like a really important insight.

Which brings me to the other thing Drezner set me off with.

The best explanation of Maggie’s work he offers — and it’s a frightfully good explanation — is the way he starts his post:

When I was curating the Toddler-in-Chief thread on Twitter and adapting it into The Toddler in Chief, I leaned pretty hard on Maggie Haberman’s reporting for the New York Times. I literally said, “Maggie Haberman’s reportage… is all over that thread.”

Drezner was talking about his interminable chronicle of Trump’s tantrums. Each tweet screen capped an example of Trump’s closest aides bitching to someone — and yes, that someone was often Maggie — about how they had to coddle Trump, how they built the entire Administration to cater to Trump’s every mood or emotion. In each tweet, Drezner the political science professor would categorize this report as yet more proof that Trump was not “growing into the presidency.” I took the observation as shorthand for false expectations of normality after Trump’s election, a hope that it wouldn’t be so bad after Trump came to understand the gravity of the office. Drezner contines to cling to that observation, even after Trump’s failed coup attempt.

I found the series funny and occasionally baited Drezner on it. It was a worthy observation about false reassurances certain pundits made about Trump. But it ended up being an inadequate rubric for understanding the damage Trump could do as we all laughed at his ineptitude.

In retrospect there were probably better ways to try to convey the danger posed by Trump than to serially mock him on Twitter, reinforcing the editorial decisions that treated his tantrums but not his actions as the news, even while exacerbating the polarization between those who identified with Trump’s tantrums and those who with their fancy PhDs knew better.

And Drezner’s first impulse, when defending Maggie’s journalism, was to point to the sheer number of times she obtained a hilarious quote that served as another artifact in a never-ending string of news stories that treated Trump’s tantrums as the news, rather than the actions Trump pulled off by training people to accommodate his tantrums.

Those stories, individually and as a corpus, revealed Trump to be a skilled bully. But those stories of Trump’s bullying commanded our attention, just like his reality TV show did, and reassured him that continued bullying would continue to dominate press coverage.

That press coverage, I’m convinced, not only was complicit in the bullying, but also served as a distraction from things that really mattered or levers that we might have used to neutralize the bullying.

It was power by reality TV. And Maggie Haberman was and remains a key producer of that power.

Update: Drezner did a really thoughtful response here. I totally agree with this point:

The part unique to Trump is his abject lack of shame. Some scandals that bring politicians down involve illegality, but most involve the revelation of actions or statements that are either embarrassing or completely at odds with their public positions. Most politicians are human beings who embarrass easily, and so are vulnerable to scandal. They will withdraw from the stage to avoid further unwanted attention. Trump’s entire career, by way of contrast, gloried in scandal. During the 2016 campaign he contradicted himself constantly, said and did repugnant things, and did not care a whit. As Ezra Klein noted way back in 2015, that was Trump’s political superpower: “This is Donald Trump’s secret, his strategy, his power…. He just doesn’t fucking care. He will never, ever give an inch. Better to be a monster than a wuss. You cannot embarrass Donald Trump.”

This would not have mattered if two other trends that I discussed at length in The Ideas Industry had not also kicked in: the rise in political polarization and the erosion of trust in institutions. These two trends created a permission structure in which ordinary Republicans could dismiss damning Maggie Haberman stories in the New York Times as fake news. Even if Haberman (and every other reporter) had published absolutely everything she knew in real time, it would not have affected this dynamic.

His discussion of how great stories reporting on scandal barely blip in the coverage, however, goes right to my biggest gripe with Maggie. Drezner denies that Maggie’s reporting serves to distract from real crimes.

The part unique to Trump is his abject lack of shame. Some scandals that bring politicians down involve illegality, but most involve the revelation of actions or statements that are either embarrassing or completely at odds with their public positions. Most politicians are human beings who embarrass easily, and so are vulnerable to scandal. They will withdraw from the stage to avoid further unwanted attention. Trump’s entire career, by way of contrast, gloried in scandal. During the 2016 campaign he contradicted himself constantly, said and did repugnant things, and did not care a whit. As Ezra Klein noted way back in 2015, that was Trump’s political superpower: “This is Donald Trump’s secret, his strategy, his power…. He just doesn’t fucking care. He will never, ever give an inch. Better to be a monster than a wuss. You cannot embarrass Donald Trump.”

This would not have mattered if two other trends that I discussed at length in The Ideas Industry had not also kicked in: the rise in political polarization and the erosion of trust in institutions. These two trends created a permission structure in which ordinary Republicans could dismiss damning Maggie Haberman stories in the New York Times as fake news. Even if Haberman (and every other reporter) had published absolutely everything she knew in real time, it would not have affected this dynamic.

But Maggie’s access and the way Trump’s associates exploit her — gleefully — makes it really easy to play her to kill a story. Her limited hangouts then become the breaking news, rather than the real details disclosed by an investigation.

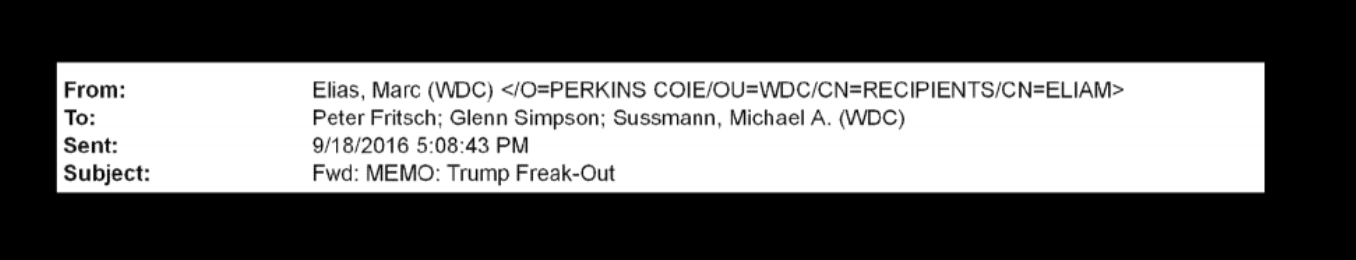

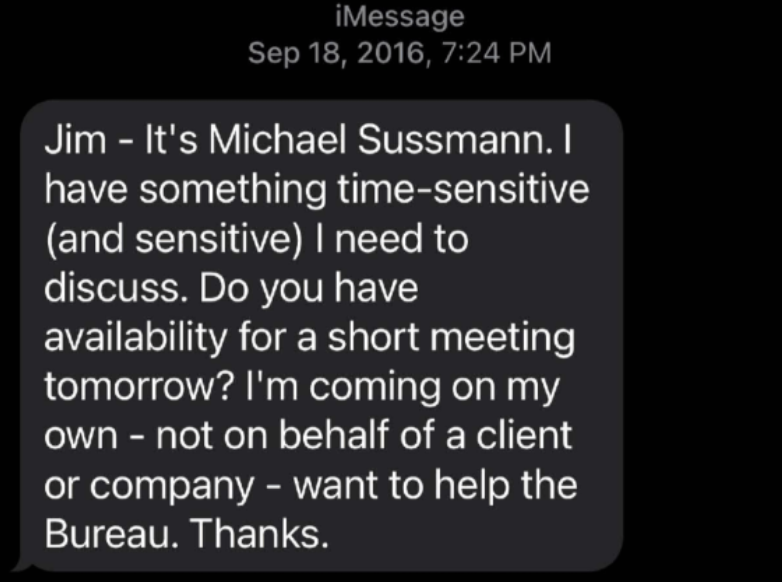

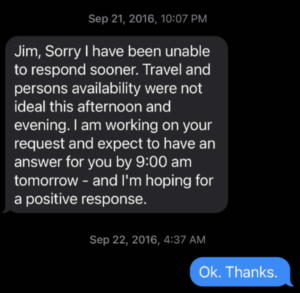

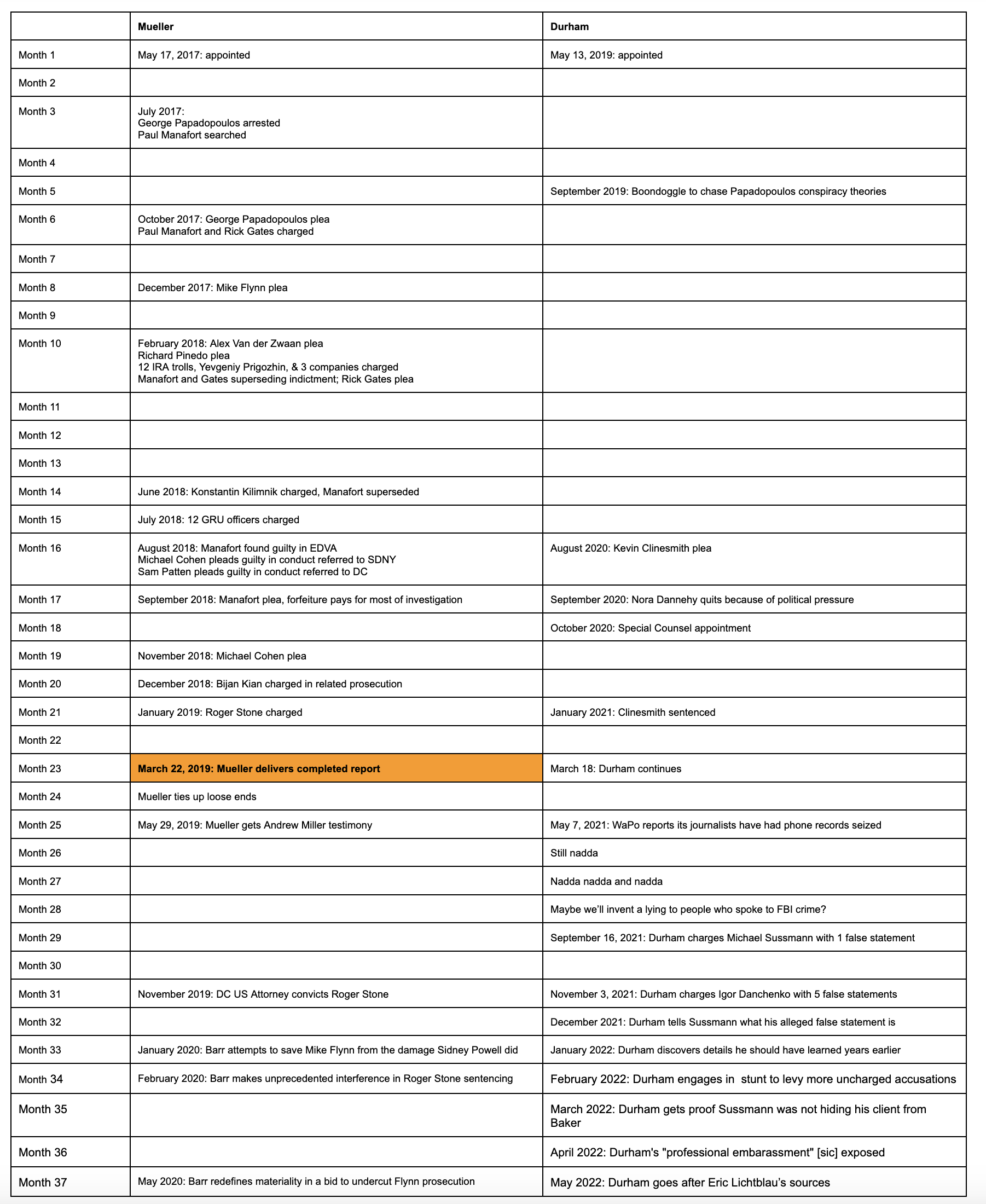

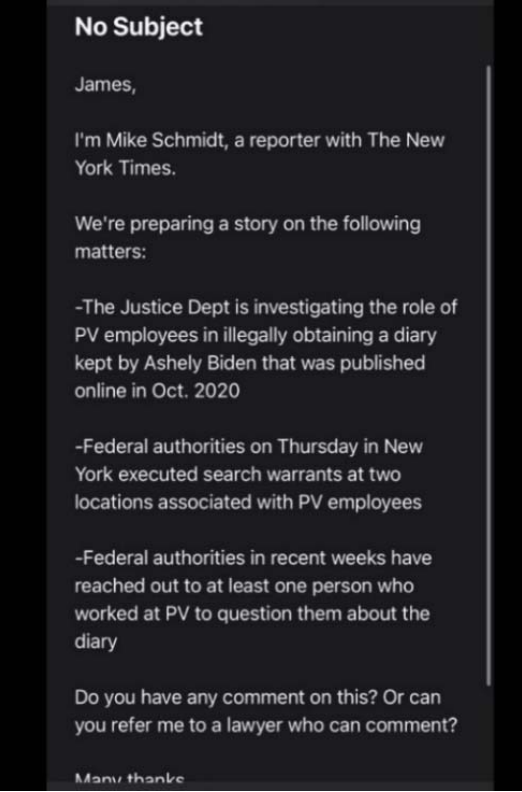

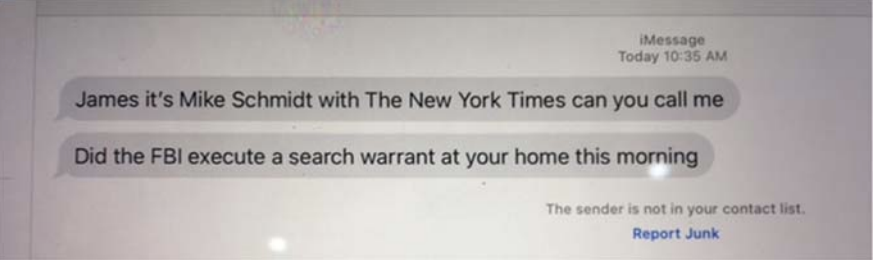

Both on specific parts of the Russian investigation — such as Paul Manafort’s sharing of campaign strategy in the same meeting where he talked about $19 million in financial benefits to him — and more generally — such as Maggie and Mike Schmidt’s demonstrably false claim that Trump was only investigated for obstruction — stories involving Maggie helped Trump and his associates cover up his criminal exposure.