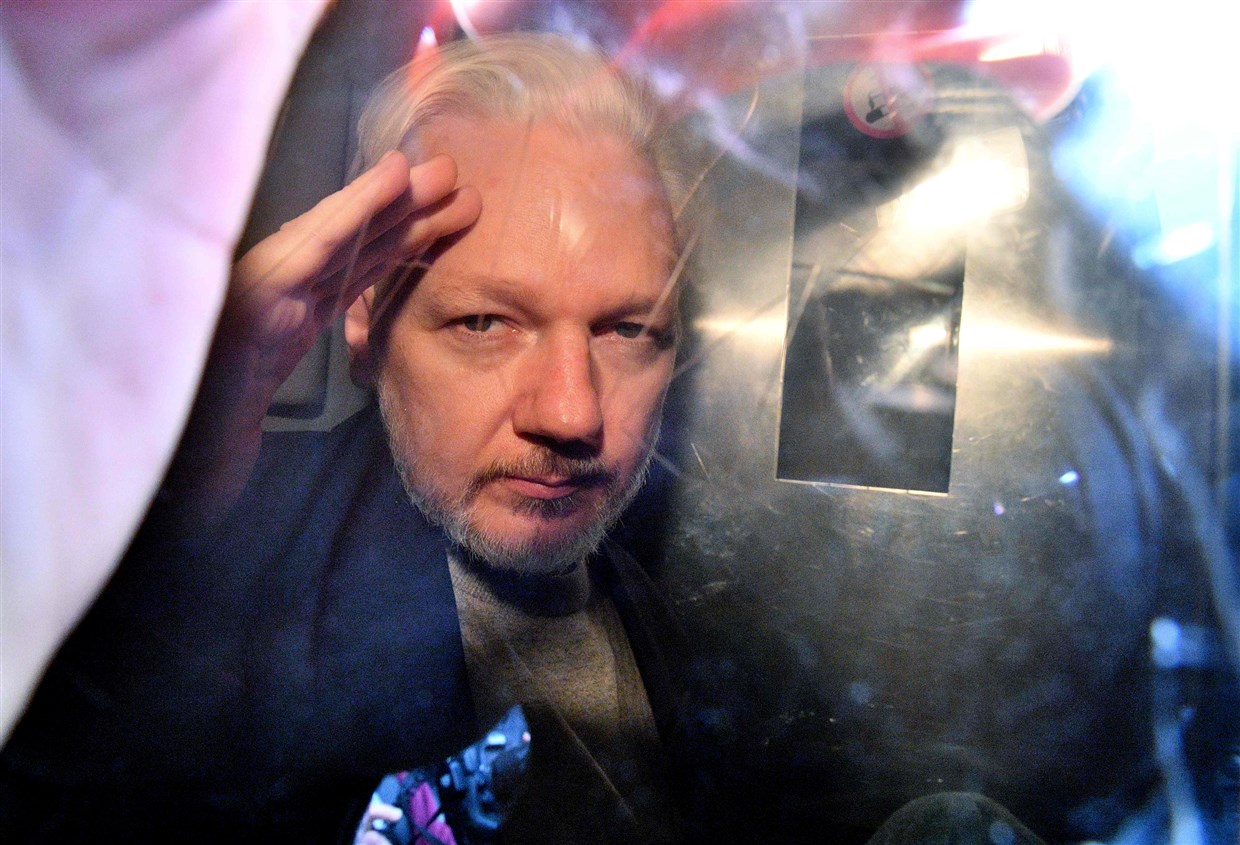

The Minh Quang Pham Precedent to the Julian Assange Extradition

WikiLeaks supporters say that extradition of Julian Assange to the United States threatens journalism. That is true.

They also say that his extradition would be unprecedented. I believe that’s true too, with respect to the Espionage Act.

But it’s not entirely without precedent. I believe the case of Minh Quang Pham, who was extradited to the US in 2015 for activities related to AQAP — the most substantive of which involve providing his graphic design expertise for two releases of AQAP’s magazine, Inspire — provides a precedent that might crystalize some of the legal issues at play.

The Minh Quang Pham case

Minh Quang Pham was born in 1983 in Vietnam. He and his parents emigrated to the UK in 1989 and got asylum. In 1995, he got UK citizenship. He partied a lot, at a young age, until his conversion to Islam in 2004, after which he was drawn to further Islamic study and ultimately to Anwar al-Awlaki’s propaganda. Pham was married in 2010 but then, at the end of that year, traveled to Yemen. After some delays, he connected with AQAP and swore bayat in early 2011. While he claimed not to engage in serious training, testimony from high level AQAP/al-Shabaab operative Ahmed Warsame, who — after a two month interrogation by non-law enforcement personnel on a ship — got witness protection for himself and his family in exchange for cooperation, described seeing Pham holding a gun, forming one basis for his firearms and terrorist training charges (though the government also relied on a photo taken with Pham’s own camera).

On my arrival, Amin had a Kalashnikov with him and a pouch of ammunition. I am not certain if he had purchased the gun himself but he did say he had been trained by Abu Anais TAIS on how to use it, I can say from my knowledge of firearms that this weapon was capable of automatic and single fire.

Warsame’s role as informant not only raised questions about the proportionality of US treatment (he was a leader of al-Shabaab, and yet may get witness protection), but also whether his 2-month floating interrogation met European human rights standards for interrogation.

Pham reportedly sucked at anything military, and by all descriptions, the bulk of what Pham did in Yemen involved helping Samir Khan produce Inspire. After some time and a falling out with Khan — and after telling Anwar al-Awlaki he would accept a mission to bomb Heathrow — he returned to the UK. He was interrogated in Bahrain and at the airport on return, and again on arrival back home, then lived in London for six months before his arrest. At first, then-Home Secretary Theresa May tried to strip him of his UK citizenship in a secret proceeding so he could be deported (and possibly drone killed like other UK immigrants), but since — as a refugee — he no longer had Vietnamese citizenship, her first attempt failed.

The moment it became clear the British effort to strip him of citizenship would fail, the US indicted Pham in SDNY on Material Support (covering the graphic design work), training with a foreign terrorist organization, and carrying a firearm. Even before he ultimately did get stripped of his citizenship, he was flown to the US, in February 2015. The FBI questioned him, with no lawyer, during four days of interviews that were not recorded (in spite of a recently instituted FBI requirement that all custodial interviews be recorded). On day four, he admitted that Anwar al-Awlaki had ordered him to conduct an attack on Heathrow (which made the 302), but claimed he had made it clear he only did so as an excuse to be able to leave and return to the UK (a claim that didn’t make the 302; here’s Pham’s own statement which claims he didn’t want to carry out an attack). While Pham willingly pled guilty to the training and arms charges, at sentencing, the government and defense disputed whether Pham really planned to conduct a terrorist attack in the UK, or whether he had — as he claimed — renounced AQAP and resumed normal life with his wife. He failed to convince the judge and got a 40 year sentence.

The question of whether Pham really did plan to attack Heathrow may all be aired publicly given that — after Pham tried to get a recent SCOTUS case on weapon possession enhancements applied to his case — the government has stated that it wants to try Pham on the original charges along with one for the terrorist attack they claim Pham planned based on subsequently collected evidence.

The parallels between the Assange and Pham cases

Let me be clear: I’m not saying that Assange is a terrorist (though if the US government tries him, they will write at length describing about the damage he did, and it’ll amount to more than Pham did). I’m arguing, however, that the US has already gotten extradition of someone who, at the time of his extradition, claimed to have injured the US primarily through his media skills (and claimed to have subsequently recanted his commitment to AQAP).

Consider the similarities:

- Both legal accusations involve suspect informants (Ahmad Warsame in Pham’s case, and Siggi and Sabu in Assange’s)

- Both Pham and Assange were charged for speech — publishing Inspire and publishing the names of US and Coalition informants — that is more explicitly prohibited in the UK than the US

- Both got charged with a substantive crime — terrorism training and possession of a gun in the case of Pham, and hacking in the case of Assange — in addition to speech-based crimes, charges that would (and did, in Pham’s case) greatly enhance any sentence on the speech-related charges

- Pham got sentenced and Assange faces a sentence and imprisonment in SuperMax in the US that is far more draconian than a sentence for the same crimes would be in the UK, which is probably a big part of the shared Anglo-American interest in extraditing them from the UK

- Whatever you think about the irregularity and undue secrecy of the Assange extradition, Pham’s extradition was far worse, particularly considering the way Theresa May was treating his UK citizenship

Unlike the Pham charges — all premised on Pham’s willing ties to a Foreign Terrorist Organization, AQAP — the US government has not included allegations that it believes Julian Assange conspired with Russia, though prosecutors involved in his case trying unsuccessfully to coerce Jeremy Hammond’s testimony reportedly told Hammond they believe him to be a Russian spy, and multiple other reports describe that the government changed its understanding of WikiLeaks as it investigated the 2016 election interference (and, probably, the Vault 7 release). Even if it’s true and even if they plan to air the basis for their belief, that’s a claimed intelligence tie, not a terrorism one.

This distinction is important. Holder v. Humanitarian Law clearly criminalizes First Amendment protected activity if done in service of a designated Foreign Terrorist Organization, so Pham’s graphic design by itself made him fair game for charges under US precedent.

The government may be moving to make a similar exception for foreign intelligence assets. As the Congressional Research Service notes, if the government believes Assange to be a Foreign Agent of Russia, it may mean the Attorney General (Jeff Sessions for the original charge, and Bill Barr for all the indictments) deemed guidelines prohibiting the arrest of members of the media not to apply.

The news media policy also provides that it does not apply when there are reasonable grounds to believe that a person is a foreign power, agent of a foreign power, or is aiding, abetting, or conspiring in illegal activities with a foreign power or its agent. The U.S. Intelligence Community’s assessment that Russian state-controlled actors coordinated with Wikileaks in 2016 may have implicated this exclusion and other portions of the news media policy, although that conduct occurred years after the events for which Assange was indicted. The fact that Ecuador conferred diplomatic status on Assange, and that this diplomatic status was in place at the time DOJ filed its criminal complaint, may also have been relevant. Finally, even if the Attorney General concluded that the news media policy applied to Assange, the Attorney General may have decided that intervening events since the end of the Obama Administration shifted the balance of interests to favor prosecution. Whether the Attorney General or DOJ will publicly describe the impact of the news media policy is unclear.

There’s a filing from the prosecutor in the case, Gordon Kromberg, that seems to address the First Amendment in more aggressive terms than Mike Pompeo’s previous statement on the topic.But it may rely, as the terrorism precedent does, on a national security exception (one even more dangerous given the absence of any State Department FTO list, but that hardly makes a difference for a foreigner like Pham).

Ultimately, though, the Assange extradition, like the Pham prosecution, is an instance where the UK is willing to let the US serve as its willing life imprisoner to take immigrants to the UK off its hands. Assange’s extradition builds off past practice, and Pham’s case is a directly relevant precedent.

The human rights case for Julian Assange comes at an awkward time

While human rights lawyers fought hard, at times under a strict gag, on Pham’s immigration case, Assange’s extradition has focused more public attention to UK’s willingness to serve up people to America’s draconian judicial system.

Last Thursday, Paul Arnell wrote a thoughtful piece about the challenge Assange will face to beat this extradition request, concluding that Assange’s extradition might (or might have, in different times) demonstrate that UK extradition law has traded subverted cooperation to a defendant’s protection too far.

We need to reappraise the balance between the conflicting functions of UK extradition law.

Among the UK’s most powerful weapons are its adherence to the rule of law, democracy and human rights. Assange’s extradition arguably challenges those fundamental principles. His case could well add to the evidence that the co-operative versus protective pendulum has swung too far.

He describes how legal challenges probably won’t work, but an appeal to human rights might.

British extradition law presumptively favours rendition. Extradition treaties are concluded to address transnational criminality. They provide that transfer will occur unless certain requirements are met. The co-operative purpose of extradition more often than not trumps the protection of the requested person.

The protective purpose of extradition is served by grounds that bar a request if they are satisfied. Those particularly applicable in Assange’s case are double criminality, human rights and oppression.

There are several offenses within the Official Secrets Acts 1911/1989 and the Computer Misuse Act 1990 that seemingly correspond to those in the US request. However, human rights arguments offer Assange hope.

Three are relevant: to be free from inhuman and degrading punishment, fair trial rights and freedom of expression. Previous decisions have held that life-terms in supermaximum-security prisons do not contravene the “punishment” provision, while the right to freedom of expression as a bar to extradition is untested.

Assange’s best prospect is possibly the oppression bar. Under it, a request can be refused on grounds of mental or physical health and the passage of time. To be satisfied, however, grievous ill health or an extraordinary delay are required.

It’s a good point, and maybe should have been raised after some of the terrorism extraditions, like Pham’s. But it may be outdated.

As I noted, Arnell’s column, titled, “Assange’s extradition would undermine the rule of law,” came out on Thursday. Throughout the same week that he made those very thoughtful points, of course, the UK publicly disavowed the rule of law generally and international law specifically in Boris Johnson’s latest effort to find a way to implement Brexit with no limits on how the UK deals with Northern Ireland.

The highlight – something so extraordinary and constitutionally spectacular that its implications are still sinking in – was a cabinet minister telling the House of Commons that the government of the United Kingdom was deliberately intending to break the law.

This was not a slip of the tongue.

Nor was it a rattle of a sabre, some insincere appeal to some political or media constituency.

No: law-breaking was now a considered government policy.

[snip]

[T]he government published a Bill which explicitly provides for a power for ministers to make regulations that would breach international and domestic law.

[snip]

Draft legislation also does not appear from nowhere, and a published Bill is itself the result of a detailed and lengthy internal process, before it is ever presented to Parliament.

This proposal has been a long time in the making.

We all only got to know about it this week.

[snip]

No other country will take the United Kingdom seriously in any international agreements again.

No other country will care if the United Kingdom ever avers that international laws are breached.

One of the new disclosures in a bunch of Roger Stone warrants released earlier this year is that, in one of the first Dms between the persona Guccifer 2.0, the WikiLeaks Twitter account explained, “we’ve been busy celebrating Brexit.” That same Brexit makes any bid for a human rights argument agains extradition outdated.