In this post I pointed out that basic economics as taught in Econ 101 relies on math and physics from the 19th Century, and complained that economists are not taking advantage of advances in both math and physics. Several commenters pointed out that there are economists working with current math tools in various ways, and of course that’s true; it just is’t taught in introductory classes. One of the new approaches is Agent-Based Modeling, which has the potential to offer new theories of the economy that focus on observed behavior rather than ideology colored with moral judgments and guesses. Here’s an introduction.

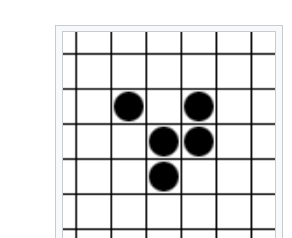

Computers introduced new areas of mathematics by making it possible to do things that take too long if done by hand. This site introduces one of these, a cellular automaton called The Game of Life. There is a simulation at the link, which is fun, and shows how powerful the idea can be. The Game of Life operates on a two-dimensional grid like a sheet of graph paper. The squares, called cells, are either empty or occupied. There is a set of rules. At each iteration, the rules are applied to every cell, and the results are entered into the grid all at once. Each cell has 8 neighbors. An occupied cell is deemed to be live, and an empty cell is dead. Here are the rules, which can be found at the link with graphics:

1) Any live cell with fewer than two live neighbors dies, as if caused by under-population.

2) Any live cell with more than three live neighbors dies, as if by overcrowding.

3) Any live cell with two or three live neighbors lives on to the next generation.

4) Any dead cell with exactly three live neighbors becomes a live cell.

Start at time 0. The machine calculates the status of each cell for the first iteration. All results are entered at once. That’s called a tick, as in a clock tick. Then the process is repeated. The iterations continue until you lose interest, or because the simulation has an artificial cut-off. Even with these simple rules, you get surprisingly complicated outcomes. Try a few experiments with the simulator (click the clear button) at the link and you’ll see.

The Game of Life is two-dimensional, but there is no reason there can’t be any number of dimensions, including one. The Game of Life operates on a limited grid of squares, but that doesn’t have to be so either. It’s possible to imagine that the Game of Life operates on the outside of an open-ended cylinder, or some other surface. Most important, the rules of the Game of Life are simple. Each rule relates solely to status of the 8 neighbors of the cell to be calculated. Again, there is no limit to the rule sets that could be used, to the number of dimensions, to the shapes of the cells, or to the cells which are considered in calculating the status of each cell. And that makes this idea useful for other purposes.

Take the simple-minded version of economics described by Katrine Marçal in Who Cooked Adam Smith’s Dinner: unchanging individuals driven solely by self-interest. That can be modeled with simple rules. First, populate a huge grid with some black squares representing individuals. We endow each of them with different quantities of three objects and we assign each cell a valuation for each object, with some variety in both. We move the individuals one square after each turn. If two black squares come into contact, they engage in the exchange of objects if and only if the exchange benefits both by increasing the total value of objects each would have after the exchange. After such an exchange, the black cells are moved some distance apart. If there is no contact, they move one cell in the same direction as the previous iteration. As a side note, we use a different definition of contact than being in one of the eight neighboring cells: each cell moves one square at each tick and thus it’s possible for two live cells to occupy the same grid square.

Let’s crank this up mentally and watch it for a while. It seems intuitively obvious that eventually each cell will have some collection of objects that would maximize their total value for each cell’s valuation criteria. Also, it’s boring. So we run it again in our head, with different movements assigned to each unit. Again, we reach a stasis perhaps with different quantities of each object in each cell. Also, boring. We could make it last longer by adding more objects.

Alternatively, we could put them to work making more objects, assigning different productivity levels to the cells. After each iteration, each cell has a bit more of one or more of the objects depending on their productivity. We run the cellular automaton again in our heads, and we see that this time it isn’t obvious that it will reach equilibrium. That’s because we put no limits on the amount of each object that the cell values more highly. That’s not right: as a general rule humans do not have a use for an unlimited amount of anything, and desire less of some things than others, and for most things there is some level of decreasing marginal utility for stuff. So we learn that we need parameters for human desire. Also we learn that we didn’t account for consumption of the objects, or wearing out, or fair wear and tear, so we need a number that will reduce the amount of each object, perhaps every few ticks, or on some other schedule.

Suppose we combine two cells into one unit with a change in priorities to model the formation of a household. That changes things too. Not only does it affect production, it changes consumption and the nature of the equilibrium. If we let the two-cell critters add a couple of more we get even more complications.

Next we introduce the firm. One way would be to use a third dimension, so that our cells could be in one one level for their individual and household behaviors and in another for their participation in a firm, so that the production part moves to the firm. Firms would have their own production rules and their own distribution rules for gains. That introduces something more like money to mediate exchanges, and changes the rules of exchange. There would have to be model banks and model hedge funds and other aggregations of capital that would deal in meta-products like cash and stocks and bonds.

We could use other levels in the third dimension, or maybe a fourth dimension to represent participation in social groups such as governments, universities, political interest groups, Churches, bowling leagues and so on. These levels would add something more to the accumulations of the individual cells, measured in units of satisfaction, or pleasure, or other forces that motivate people. This could include negative forces like racism, hostility, and agression.

So far, the game is determinate, and does not model reality, which is contingent. To fix that, we allow the various levels to change the valuation of the objects of accumulation. To speed up the calculation, the code would use look-up tables for all the variables to determine the changes between ticks. So the various levels or dimensions could change the look-up tables in sensible ways, and occasionally in ways that aren’t so sensible. For example, the individual would change the value of some object not needed in a paired state, or needed because of “children”. The government state could change the value of the “tax”. The firm could change the valuation of the product. Or it could add a new product and set up a value. And so on. The Fed model can change interest rates. The government level could change its acquisition patterns.

This sketch suggests that we could create a very complicated model, with thousands of rules and calculations. But with efficient use of look-up tables, simple calculations and highly parallel operations, it’s just the kind of problem computers are good at.

To make this idea usable, there are open platforms for creation of models like this. Here’s one called Repast, and another called Swarm. And here’s a link to an exercise in modeling that raises interesting issues using Thomas Piketty’s r > g idea. Here’s a difficult article entitled Cellular Automata based Artificial Financial Market by Jingyuan Ding of Shanghai University China. The writer created a cellular automaton to model the capital markets.

Any tool can and will be misused. For example, economists could use existing theories of human behavior in constructing models. That would be a terrible mistake. The closer we get to empirically derived rules, the closer we get to a set of ideas about the economy that do not depend on assumptions like the efficient market hypothesis or that humans are solely rational utility-maximizers. A good test is whether the model produces booms and busts, common features in reality.

One good thing is that platforms like Repast and Swarm are used by modelers from other scientific fields like biology and political science. That might enable economists to learn from people outside their specialty. We can always hope.