The first day of the Julian Assange extradition hearing was a predictable circus.

Assange’s lawyers tried two legal tactics.

First, they tried to get parts of the second superseding indictment excluded from the proceedings. They claimed they hadn’t had time to review it with Assange. While I’m sympathetic to the difficulties imposed by Assange’s imprisonment amid COVID measures, WikiLeaks supporters have at the same time been (correctly) complaining that the documents on which the new allegations are based have been public for some time.

In any case, it didn’t work. Judge Vanessa Baraister said that she had offered Assange the opportunity to raise this complaint in the last hearing.

Judge Baraister similarly rejected a bid to delay the hearing until January (not incidentally the period when, if a Trump pardon for Assange would be forthcoming, it would take place), on largely the same basis.

Next, Professor Mark Feldstein — a journalism professor at University of Maryland — tried to present his testimony. Technical problems forced Baraister to delay proceedings until tomorrow.

That has left the public with copies of Feldstein’s prepared testimony and a supplement before he has the opportunity to present it and lawyers for the US to grill him in response. That may be unfortunate, because Feldstein’s original testimony has some key errors and omissions, and in his supplement he professes a lack of familiarity with the public record in this case.

Let me be clear: I wholeheartedly agree with large swaths of Professor Feldstein’s testimony. Donald Trump has waged unprecedented attacks on members of the news media, both verbally and through policy. I agree, too, that the First Amendment is not limited to journalists, and that political advocacy like Assange’s has a storied place in the history of journalism. I agree that some of the stories based off Chelsea Manning’s leaks were blockbusters (Feldstein predictably starts by listing Collateral Murder, which is not charged, and his effort to include all the files that were charged strays much further from the ones that have been most important.) His history of classified leaks is useful, though in some places he seems to misunderstand what was new and what wasn’t revealed until the release of declassified documents. His statement speaks at length about the dire problem with overclassification (though in one case, he cites a John McCain accusation about Obama’s motive for leaking as fact, a claim that hasn’t held up to subsequent events; he later cites McCain as a classification villain). I even agree with some, though not all, of his analysis of how the charges against WikiLeaks threaten normal journalistic activities like soliciting, receiving, and publishing documents, and protecting confidential sources. (Feldstein never goes so far as to defend helping a source hack something.) His testimony is valuable for the background on journalism it offers.

But Feldstein’s account of how the Assange prosecution arose out of Donald Trump’s election — which occurred with Assange’s help!!! — not only invents claims he doesn’t support, but makes several telling errors in citation.

Donald Trump’s election changed the calculus. The month after his inauguration, the president met with FBI director James Comey and brought up the issue of plugging leaks. Comey suggested “putting a head on a pike as a message” and Trump recommended “putting reporters in jail.”83 Three days later, he instructed his attorney general to investigate “criminal leaks” of “fake” news reports that had embarrassed the White House.84 According to press accounts, the new administration soon “unleashed an aggressive campaign” against Assange. CIA director Mike Pompeo publicly attacked WikiLeaks as a “hostile intelligence service” that uses the First Amendment to “shield” himself from “justice.” In private, he briefed members of Congress on a bold counterintelligence operation the agency was conducting that included the possible use of informants, penetrating overseas computers, and even trying to directly “disrupt” WiliLeaks, a move that made some lawmakers uncomfortable.85 A week later, Attorney General Jeff Sessions said at a news conference that journalists “cannot place lives at risk with impunity,” that prosecuting Assange was a “priority” for the new administration, and that if “a case can be made, we will seek to put some people in jail.” 86 The new leaders at the Justice Department dismissed their predecessors’ interpretation that Assange was legally indistinguishable from a journalist and reportedly began “pressuring” their prosecutors to outline an array of potential criminal charges against him, including espionage. Once again, career professionals were said to be “skeptical” because of the First Amendment issues involved and a “vigorous debate” ensued. 87 Two prosecutors involved in the case, James Trump and Daniel Grooms, reportedly argued against charging Assange.88 But in April of 2019, Assange was arrested in London—even though “the Justice Department did not have significant evidence or facts beyond what the Obama-era officials had when they reviewed the case.”89

83 Abramson, “Comey’s wish for a leaker’s ‘head on a pike.’”

84 “Remarks by President Trump in Press Conference,” WH.gov (Feb. 16, 2017); Charlie Savage and Eric Lichtblau, “Trump Directs Justice Department to Investigate ‘Criminal Leaks,’” New York Times (Feb. 16, 2017); Barnes, et al, “How the Trump Administration Stepped up Pursuit of WikiLeaks’ Assange.”

85 CIA, “Director Pompeo Delivers Remarks at CSIS” (April 13, 2017): www.cia.gov/news-information/speechestestimony/2017-speeches-testimony/pompeo-delivers-remarks-at-csis.html.

86 “Sessions Delivers Remarks,” Justice.gov. [sic]

87 Matt Zapotosky and Ellen Nakashima, “Justice Department debating charges against WikiLeaks members,” Washington Post (April 20, 2017); Adam Goldman, “Justice Department Weighs Charges Against Julian Assange,” New York Times (April 20, 2017).

88 Devlin Barrett, Matt Zapotosky and Rachel Weiner, “Some federal prosecutors disagreed with decision to charge Assange under Espionage Act,” Washington Post (May 24, 2019). 89 Barrett, et al, “Prosecutors Disagreed.”

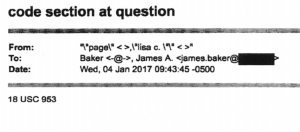

The first citation (83) is to a 2018 story on Jim Comey’s memos memorializing conversations about leaks damaging to Trump, not WikiLeaks. The second (84) refers to an effort to go after those who damaged Trump. The next three sentences are attributed to Mike Pompeo’s designation of WikiLeaks as a non-state hostile actor in April 2017 (85), in the wake of the Vault 7 leaks, but two of those sentences (bolded) are not actually sourced to Pompeo’s comments, but instead to news accounts not specified in the relevant footnote. The next sentence combines what Jeff Sessions said on April 20, 2017 and what he said on August 4, 2017; perhaps Feldstein aims to cover that up by not including a date or a citation in the remarks in question (see footnote 86; Sessions’ April 20 comments don’t appear to be on the DOJ website), but suggesting Sessions’ August comments were about Assange is a move that WikiLeaks has made elsewhere. Importantly, Feldstein does not footnote one of the most widely cited reports of that April 20 speech, a CNN report that describes what changed, already in 2017, since DOJ had earlier decided not to prosecute Assange.

The US view of WikiLeaks and Assange began to change after investigators found what they believe was proof that WikiLeaks played an active role in helping Edward Snowden, a former NSA analyst, disclose a massive cache of classified documents.

[snip]

US intelligence agencies have also determined that Russian intelligence used WikiLeaks to publish emails aimed at undermining the campaign of Hillary Clinton, as part of a broader operation to meddle in the US 2016 presidential election. Hackers working for Russian intelligence agencies stole thousands of emails from the Democratic National Committee and officials in the Clinton campaign and used intermediaries to pass along the documents to WikiLeaks, according to a public assessment by US intelligence agencies.

That is, if Feldstein had reviewed the press coverage more broadly, he would have a ready explanation for why DOJ began to rethink its earlier decision not to charge Assange.

Assange’s own filing may attempt to cover for Feldstein’s citation inaccuracy, claiming that Feldstein cited that April WaPo story rather than ““Sessions Delivers Remarks,” Justice.gov”.

Then came the political statement of Attorney General Sessions on 20 April 2017 that the arrest of Julian Assange was now a priority and that ‘if a case can be made, we will seek to put some people in jail’ [Feldstein quoting Washington Post article of Ellen Nakashima, tab 18, p.19].

But even that April 20, 2017 WaPo article he claims to rely on doesn’t help him. In fact, it disputes Feldstein’s account of Trump’s animus towards WikiLeaks.

Trump has had a fluid relationship with WikiLeaks, depending largely on how the group’s actions benefited or harmed him. On the campaign trail, when WikiLeaks released Podesta’s hacked emails, Trump told a crowd in Pennsylvania, “I love WikiLeaks!” But when it came to the release of the CIA tools, he did not seem so pleased.

“In one case, you’re talking about highly classified information,” Trump said at a news conference earlier this year. “In the other case, you’re talking about John Podesta saying bad things about the boss.”

The actual words cited in part to the WaPo in Feldstein’s testimony (naming Ellen Nakashima, not Matt Zapotosky) don’t appear in the April story but in the NYT story cited. The rest relies on a [Devlin Barret and] Zapotosky story fairly obviously sourced to prosecutor James Trump, whom Zapotosky covered in the Jeffrey Sterling case and other EDVA cases but who — the story admits — wasn’t on the team anymore even when Assange was originally charged (presumably meaning December 2017 on just a CFAA charge that would accord with AUSA Trump’s concerns about an Espionage charge), and who would therefore have no visibility into what went into the May 2018 superseding indictment of Assange, much less the one on the table now.

In short, a key paragraph in Feldstein’s testimony, which is cited repeatedly in both Assange’s briefs on the case (one, two), is a scholarly shit-show.

And that’s before you consider the chronology of it, omitting as it does the Vault 7 leak which all the Assange-specific comments were responding to, which started on March 7, 2017.

That’s not the only problem with Feldstein’s citations. Feldstein also footnotes a claim that Assistant Attorney General for DOJ’s National Security Division John Demers, “declared that ‘Julian Assange is no journalist’ and thus not protected under the free press clause of the US Constitution’s First Amendment” with a citation to news reports on the indictment, rather than the remarks as prepared rolling out the indictment. While the story from Charlie Savage that Feldstein cites responsibly quotes Demers in context, the full statement makes it clear that it’s not only not a comment directly about the First Amendment, but that Demers never mentions the First Amendment.

The Department takes seriously the role of journalists in our democracy and we thank you for it. It is not and has never been the Department’s policy to target them for their reporting.

Julian Assange is no journalist. This made plain by the totality of his conduct as alleged in the indictment—i.e., his conspiring with and assisting a security clearance holder to acquire classified information, and his publishing the names of human sources.

Indeed, no responsible actor—journalist or otherwise—would purposely publish the names of individuals he or she knew to be confidential human sources in war zones, exposing them to the gravest of dangers.

This continues WikiLeaks’ longstanding effort to suggest the government has made First Amendment claims about Assange that obscure what they have actually said. (AUSA Gordon Kromberg does appear to have addressed the First Amendment in ways WikiLeaks has claimed that others have, but his affidavit is not yet public.)

While Kromberg’s testimony is not yet public, in one of the government’s filings made public today, the government hints at what Kromberg may have said at more length, noting that Feldstein only cites part of — but not the entirety — of a news report on Assange.

The principal evidence upon which the defence relies to demonstrate the existence of a such a decision is a newspaper article dated 25 November 2013 [Sari Horowitz, “Julian Assange is unlikely to face US Charges over publishing classified documents”, Washington Post]; Cited by Professor Feldstein at §9 page 18. 39.

Professor Feldstein omits important sections of the report upon which he relies to demonstrate a “decision” not to prosecute:

“The officials stressed that a formal decision has not been made, and a grand jury investigating WikiLeaks remains impaneled, but they said there is little possibility of bringing a case against Assange, unless he is implicated in criminal activity other than releasing online top-secret military and diplomatic documents.

And:

“WikiLeaks spokesman Kristinn Hrafnsson said last week that the anti-secrecy organization is skeptical “short of an open, official, formal confirmation that the U.S. government is not going to prosecute WikiLeaks.” Justice Department officials said it is unclear whether there will be a formal announcement should the grand jury investigation be formally closed”.

So, in response to Kromberg, Feldstein dug himself a very much deeper hole.

In a supplemental filing, Assange expert witness Mark Feldstein claimed and exhibited that he’s not familiar with the public record (though he cleaned up some of his prior citation errors). In it, he claimed the only way to know the truth about the Assange prosecution would be from leaks of grand jury or White House documents. “[T]he reporting I cited by the New York Times and Washington Post is to date the only public source of information about the behind-the-scenes maneuvering to prosecute Assange,” he claimed in a filing submitted on July 5, 2020.

The government insists that the Trump administration’s prosecution of Assange is not politically motivated. It dismisses my contrary conclusion—and that of other expert witnesses—by saying that we “primarily rely on a select number of news articles…and the hearsay within them.”

Indeed, my declaration relied on news accounts that the Obama administration decided not to prosecute Assange because of concerns that doing so would violate the First Amendment. 2 In particular, I cited comments that Matthew Miller, the former spokesman for the Obama Justice Department, made in an interview with the Washington Post: “The problem the department has always had in investigating Julian Assange is there is no way to prosecute him for publishing information without the same theory being applied to journalists. And if you’re not going to prosecute journalists for publishing classified information, which the department is not, then there is no way to prosecute Assange.” The Post reported that prosecutors called this the “New York Times problem”—that if they indicted Assange for publishing the documents leaked by Chelsea Manning, then they would also have to also indict the New York Times for doing the same.3

I also noted that the Trump administration decide to reject this interpretation and cited a New York Times report that its new appointees running the Justice Department began “pressuring” prosecutors to indict Assange, although two career prosecutors argued against doing so on First Amendment grounds. I also cited the article’s finding that “the Justice Department did not have significant evidence or facts beyond what the Obama-era officials had when they reviewed the case”4 and concluded that the decision to indict Assange was not an evidentiary decision but a political one.5

As the government knows, internal prosecutorial deliberations are not a matter of public record. White House and Justice Department documents that would shed further light on the political dimensions of the case—emails, internal memos, grand jury transcripts, and other records—are kept secret by the government. Thus, the reporting I cited by the New York Times and Washington Post is to date the only public source of information about the behind-the-scenes maneuvering to prosecute Assange.

Like so much other questionable conduct by the Trump administration, revelations about the unorthodox nature of this prosecution came to light only because of the vigilance of a free and vigorous press.

1 Gordon D. Kromberg, “Declaration in Support of Assange Extradition,” US v. Assange (Jan. 17, 2020), ¶18-19, pp. 8- 9.

You have got to be fucking kidding me!!

I invite Professor Feldstein to assign his undergraduate journalism students with the task of trying to discover any Trump, White House, and National Security views about WikiLeaks and Julian Assange that might explain why DOJ decided not to prosecute in 2013 but did prosecute in 2017, 2019, and 2020.

His first year undergraduate students might note the proximity between the April 2017 Assange-related announcements (the Jeff Sessions of which he obscures with his dodgy citation) and the release of the Vault 7 files in March 2017, which burned the CIA hacking ability to the ground.

They also might point to Trump’s tweets celebrating WikiLeaks to suggest that while Trump might hate the traditional press, he spent most of the 2016 campaign celebrating WikiLeaks.

Feldstein’s second year undergraduate students might look to the obvious places — like the Mueller Report — for some views about how Trump ordered campaign staff to go chase down WikiLeaks’ releases. Not only do the descriptions completely undermine Feldstein’s claim that Trump treats WikiLeaks like he does traditional media outlets, but it shows that the Department of Justice conducted an extensive investigation implicating WikiLeaks after the 2013 Matthew Miller quote he relies on. Indeed, exceptional sophomores might note that a redaction error in the Mueller Report makes it clear that a Mueller prosecutorial decision about foreign donations pertains to WikiLeaks, a detail released in 2019 that James Trump would not have been privy to.

Junior year journalism students might refer to the Stone trial testimony to see what it said about Trump’s relationship with WikiLeaks. Really astute journalism students would note that Randy Credico testified that Donald Trump’s rat-fucker Roger Stone actually reached out to Randy Credico in an effort to broker a pardon for Assange.

Q. Had you put Mr. Stone directly in touch with Ms. Kunstler after the election?

A. Yes, I did.

Q. And why had you done that?

A. Well, sometime after the election, he wanted me to contact Mrs. Kunstler. He called me up and said that he had spoken to Judge Napolitano about getting Julian Assange a pardon and needed to talk to Mrs. Kunstler about it. So I said, Okay. And I sat on it. And I told her–I told her–she didn’t act on it. And then, eventually, she did, and they had a conversation.

The same astute budding journalists might look at the trial record and discover how long those pardon discussions lasted — continuing well past the time Mike Pompeo and Jeff Sessions were discussing prosecuting journalists and/or Assange.

Senior journalism students might even tie that testimony to a question Robert Mueller asked — but didn’t really get an answer about — regarding whether Trump had considered an Assange pardon.

Donald Trump refused to answer a question under oath about whether he considered pardoning Julian Assange during the transition period between when WikiLeaks releases helped get him elected and his inauguration, something that makes it pretty clear the President treats WikiLeaks and Assange, which helped him get elected, differently than he does journalists who did not.

Professor Feldstein says he’d need a leak to discover that.

There’s a slew more that graduate students might discover but that Feldstein professed to be helpless to discover himself, such as the warrant that makes it clear Stone reached out to WikiLeaks lawyer Margaret Kunstler — to discuss an Assange pardon, WikiLeaks supporter Randy Credico testified to under oath — seven days after Trump got elected.

Or the other Stone warrant making it clear that after several of the media reports Feldstein relies on, Mueller’s team was just beginning to obtain warrants implicating Assange, in part for election-related crimes that have nothing to do with the Espionage Act. Or yet another that suggests DOJ was investigating WikiLeaks, in part, for conspiracy and Foreign Agent charges in August 2018.

Diligent journalism students — budding journalists not intimidated by redaction marks — might even look to the multiple SSCI Reports that address the government’s evolving understanding of WikiLeaks, particularly those that show how the many conflicting views in 2016 came to change to believe that WikiLeaks had been coopted by Russia.

Despite Moscow’s history of leaking politically damaging information, and the increasingly significant publication of illicitly obtained information by coopted third parties, such as WikiLeaks, which historically had published information harmful to the United States. previous use of weaponized information alone was not sufficient for the administration to take immediate action on the DNC breach. The administration was not fully engaged until some key intelligence insights were provided by the IC, which shifted how the administration viewed the issue.

Here, in public view, is indication that not just DOJ but the entire Intelligence Community came to shift their view of WikiLeaks and Assange as they investigated how Russia had attacked US democracy in 2016. But Mark Feldstein testified in his supplemental testimony that he could only discover that if someone leaked it to him.

Finally, Feldstein’s students might seek to understand the workings of a grand jury from the same place journalists always have, from those called to testify before them. Had they done so, they would at a minimum discover the Jeremy Hammond description of how he refused to testify for what would be the last superseding indictment against Assange, in which he described prosecutors twice claiming (without evidence) that Assange is “a Russian spy.”

“What could the United States government do that could get you to change your mind and obey the law here? Cause you know” — he basically says — “I know you think you’re doing the honorable thing here, you’re very smart, but Julian Assange, he’s not worth it for you, he’s not worth your sacrifice, you know he’s a Russian spy, you know.”

[snip]

He implied that all options are on the table, they could press for — he didn’t say it directly, but he said they could press for criminal contempt. … Then he implies that you could still look like you disobeyed but we could keep it a secret — “nobody has to know I just want to know about Julian Assange … I don’t know why you’re defending this guy, he’s a Russian spy. He fucking helped Trump win the election.”

The claims of a prosecutor as he’s trying to coerce testimony don’t affirm the veracity of the claim. Hammond’s claims in no way prove that Assange is a Russian spy or even that DOJ believes he is. But it does indicate what DOJ’s then-current claims were, in March 2020, before the most recent superseding indictment against Assange. They would indicate that the prosecutors asking for the extradition of Julian Assange claim to believe he is a Russian spy.

There is an embarrassment of public documents describing how the US government’s view of Assange changed between 2013 and 2020, as well as plenty that show DOJ was obtaining new legal process well after DOJ decided not to prosecute Assange. That doesn’t mean their view is correct or that it in any way mitigates the risk to journalism. But it does mean their view is discoverable by anyone who wants to check the public record.

And yet journalism Professor Mark Feldstein professes to be helpless to explain why DOJ charged Assange in 2017 and 2019 and 2020 but not in 2013, not unless someone leaks to him what DOJ and Trump and the rest of the US government were really thinking. And so instead, he offered a paragraph that falls apart completely if you simply read his source material, to say nothing of the public record.

Feldstein gives himself a bit of an excuse by claiming that his scholarly statement doesn’t address what happened after 2011 (a focus that may come from WikiLeaks’ lawyers — recall that someone close to Assange scolded me for reporting accurately on what WikiLeaks had done in 2016 and afterwards).

It should be noted that this report addresses only WikiLeaks disclosures in 2010-2011, the time period when Assange is accused of violating the Espionage Act; it does not discuss the website’s previous or subsequent document releases.

But you can’t claim to provide expert testimony about what DOJ was doing in 2017 without considering what WikiLeaks had done in the interim, and how that might change investigative tactics and conclusions (and did, in fact, lead DOJ to reconsider the evidence they had).

The record shows that — far from treating Assange with the disdain Trump harbored towards traditional journalists — Trump’s close associates entertained numerous discussions about pardons, and Trump himself refused to deny that under oath to Mueller. It further shows that the targeting of Wikileaks immediately followed the Vault 7 leaks burned the CIA’s hacking capacity to the ground (a prosecution that Trump himself almost blew up hours before the FBI confiscated Schulte’s passports). Finally, there is an abundance of evidence discoverable in the public record by any diligent journalism student that the understanding of WikiLeaks significantly evolved after the decisions not to charge Assange in 2013, in part because a national security investigation sought to figure out how badly Russians had tampered in our election, and in part because Trump got all kinds of help in the election from foreigners (including Assange).

Mark Feldstein claims in his expert testimony that what is happening to Julian Assange is just part of Trump’s larger assault on the press.

Seen in this light, the administration’s prosecution of Julian Assange is part and parcel of its campaign against the news media as a whole. Indeed, Assange’s criminal indictment under the US Espionage Act is arguably its most important action yet against the press, with potentially the most far-reaching consequences.

But he makes that claim while also admitting zero familiarity about the public record concerning Assange which shows the opposite.

The Julian Assange prosecution presents serious risks to journalism. But none of those excuse shoddy journalism — a failure to even consult the public, official record — in support of his case. That’s what Assange’s first witness is planning to do.

Update: Cleaned up the post and fixed a date.