On the Shoddy Journalistic Defense of “WikLeaks”

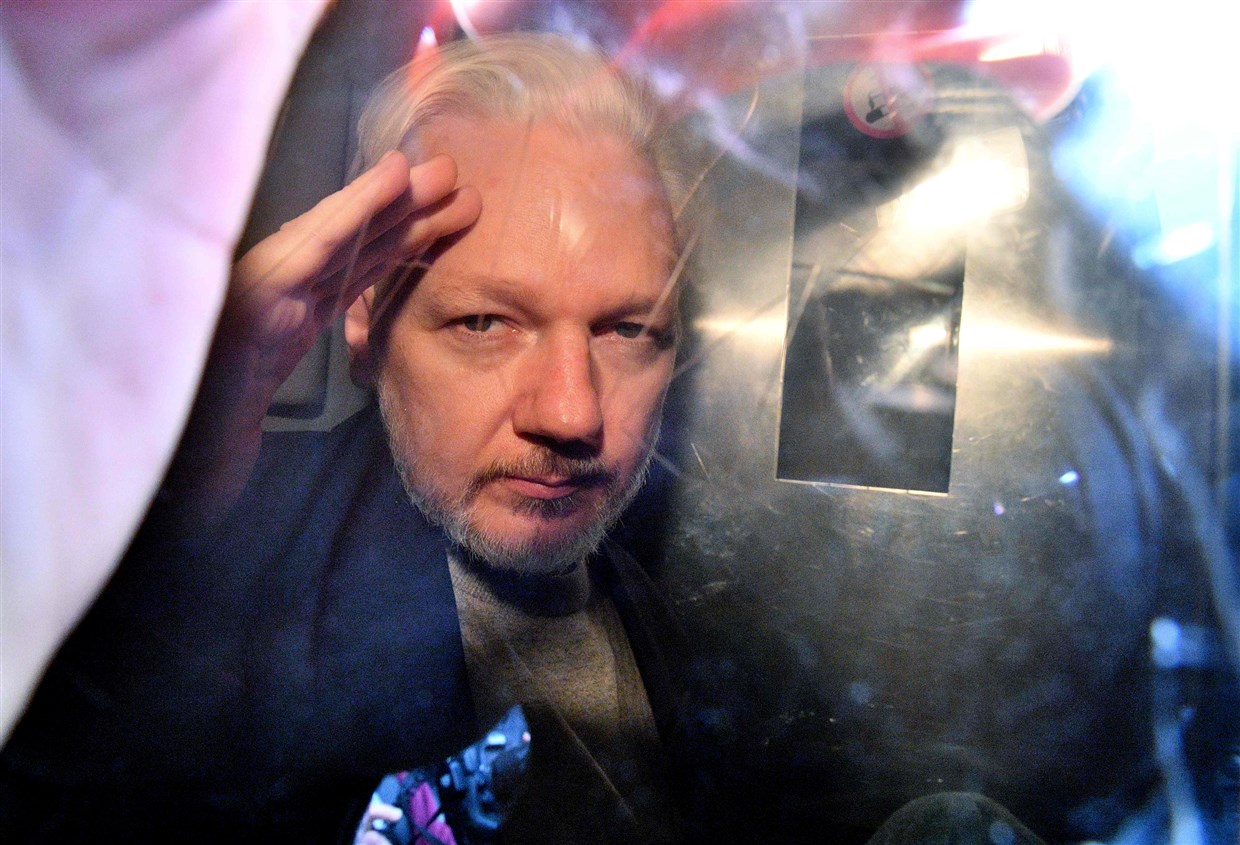

When it was first published, a letter that the NYT, Guardian, Le Monde, Der Spiegel, and El País signed, calling on the US government to drop the Espionage Act charges against Julian Assange, got the date of Assange’s arrest wrong — it was April 11, not April 12, 2019. The outlets have since corrected the error, though without crediting me for alerting them to it.

A correction was made on Nov. 29, 2022: An earlier version of this letter misstated the date of Julian Assange’s 2019 arrest. It was April 11th, not April 12th.

An email was sent by me and then a correction was made. No bill was sent for the free fact checking.

As it currently exists, even after correcting that error, the Guardian version of the letter misspells WikiLeaks: “WikLeaks.”

For Julian Assange, publisher of WikLeaks, the publication of “Cablegate” and several other related leaks had the most severe consequences. On [April 11th] 2019, Assange was arrested in London on a US arrest warrant, and has now been held for three and a half years in a high-security British prison usually used for terrorists and members of organised crime groups. He faces extradition to the US and a sentence of up to 175 years in an American maximum-security prison. [my emphasis]

The slovenly standards with which five major newspapers released this letter suggest the other inaccuracies in the letter may be the result of sloppiness or — in some cases — outright ignorance about the case on which they claim to comment.

Take the claim Assange could serve his sentence in “an American maximum-security prison.” The assurances on which British judges relied before approving the extradition included a commitment that the US would agree to transfer Assange to serve any sentence, were he convicted, in Australia.

Ground 5: The USA has now provided the United Kingdom with a package of assurances which are responsive to the judge’s specific findings in this case. In particular, the US has provided assurances that Mr Assange will not be subject to SAMs or imprisoned at ADX (unless he were to do something subsequent to the offering of these assurances that meets the tests for the imposition of SAMs or designation to ADX). The USA has also provided an assurance that they will consent to Mr Assange being transferred to Australia to serve any custodial sentence imposed on him if he is convicted.

While the assurances that Assange wouldn’t be subject to Special Administrative Measures (basically contact limits that amount to isolation) aren’t worth the paper they were written on — partly because Assange did so much at the Ecuadorian Embassy that, if done in a US jail, would get him subject to SAMs, and partly because the process of designation under SAMs is so arbitrary — reneging on the agreement to transfer Assange to Australia would create a significant diplomatic row. A sentence in an American maximum-security prison is explicitly excluded from the terms of the extradition before Attorney General Garland, unless Assange ultimately chose to stay in the US over Australia (or Australia refused to take him).

The claim that he could be sentenced to 175 years, when the reality is that sentencing guidelines and concurrent sentences would almost certainly result in a fraction of that, is misleading, albeit absolutely within the norm for shoddy journalism about the US legal system. It’s also needlessly misleading, since any sentence he would face would be plenty draconian by European standards. Repeating a favorite Assange line, one that is legally true but practically misleading, does little to recommend the letter.

In the next paragraph, these five media outlets seem to suggest that the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act conspiracy alleged in “the indictment” is limited to Assange’s effort to crack a password.

This group of editors and publishers, all of whom had worked with Assange, felt the need to publicly criticise his conduct in 2011 when unredacted copies of the cables were released, and some of us are concerned about the allegations in the indictment that he attempted to aid in computer intrusion of a classified database. But we come together now to express our grave concerns about the continued prosecution of Julian Assange for obtaining and publishing classified materials.

It is — in the 2017 to 2019 charging documents. But not the one on which Assange is being extradited.

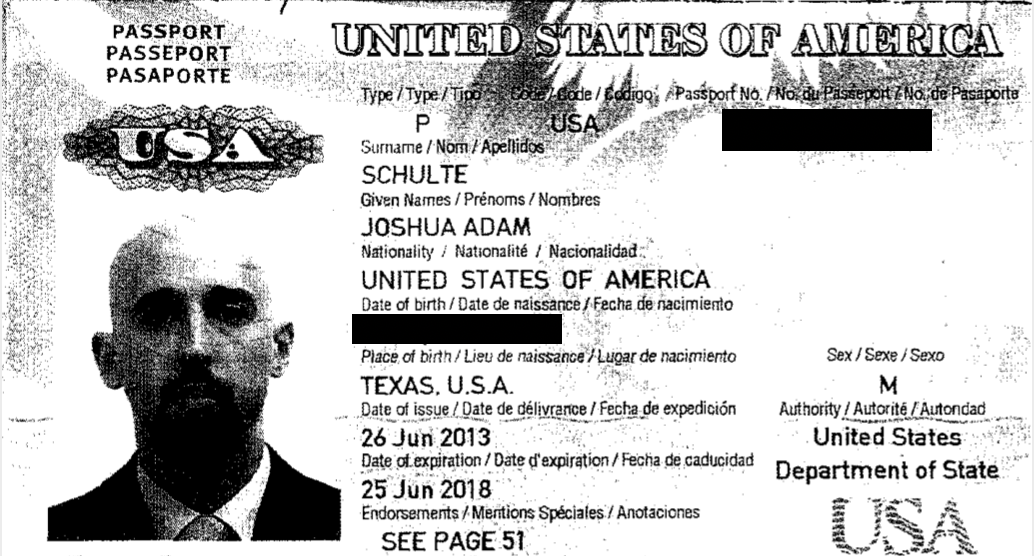

The hacking conspiracy, as currently charged, is a 5-year conspiracy that alleges far more than — and starts before — the password cracking seemingly described in the paragraph. It includes Assange’s use of Siggi’s credentials to access a police database to monitor any investigation into himself, a request to hack a former WikiLeaks associate, the recruitment of Anonymous hackers to target US-based companies (arguably also an attempt to aid in the computer intrusion of classified databases, albeit not US government ones), and the exploitation of WikiLeaks’ role in helping Edward Snowden flee to recruit more hacks including, explicitly, a sysadmin hack of the CIA’s classified databases like the one for which Joshua Schulte has now been convicted. (The existing indictment ends at 2015, before the start of Schulte’s actions, though I would be unsurprised to see a superseding indictment incorporating that hack, leak, and exposure of sensitive identities.)

Are these media outlets upset that DOJ has charged Assange for a conspiracy in which at least six others have been prosecuted, including in the UK? Are they saying that’s what their own journalists do, recruit teenaged fraudsters who in turn recruit hackers for them? Or are these outlets simply unaware of the 2020 indictment, as many Assange boosters are?

Whichever it is, it exhibits little awareness of the import that Judge Vanessa Baraitser accorded the hacking conspiracy to distinguish Assange’s actions from actual journalism.

At the same time as these communications, it is alleged, he was encouraging others to hack into computers to obtain information. This activity does not form part of the “Manning” allegations but it took place at exactly the same time and supports the case that Mr. Assange was engaged in a wider scheme, to work with computer hackers and whistle blowers to obtain information for Wikileaks. Ms. Manning was aware of his work with these hacking groups as Mr. Assange messaged her several times about it. For example, it is alleged that, on 5 March 2010 Mr. Assange told Ms. Manning that he had received stolen banking documents from a source (Teenager); on 10 March 2010, Mr. Assange told Ms. Manning that he had given an “intel source” a “list of things we wanted and the source had provided four months of recordings of all phones in the Parliament of the government of NATO country-1; and, on 17 March 2010, Mr. Assange told Ms. Manning that he used the unauthorised access given to him by a source, to access a government website of NATO country-1 used to track police vehicles. His agreement with Ms. Manning, to decipher the alphanumeric code she gave him, took place on 8 March 2010, in the midst of his efforts to obtain, and to recruit others to obtain, information through computer hacking

[snip]

In relation to Ms. Manning, it is alleged that Mr. Assange was engaged in these same activities. During their contact over many months, he encouraged her to obtain information when she had told him she had no more to give him, he identified for her particular information he would like to have from the government database for her to provide to him, and, in the most obvious example of his using his computer hacking skills to further his objective, he tried to decipher an alphanumeric code she sent to him. If the allegations are proved, then his agreement with Ms. Manning and his agreements with these groups of computer hackers took him outside any role of investigative journalism. He was acting to further the overall objective of WikiLeaks to obtain protected information, by hacking if necessary. Notwithstanding the vital role played by the press in a democratic society, journalists have the same duty as everyone else to obey the ordinary criminal law. In this case Mr. Assange’s alleged acts were unlawful and he does not become immune from criminal liability merely because he claims he was acting as a journalist.

Whether editors and publishers at the five media outlets know that Assange was superseded in 2020 or not or just used vague language that could be read, given the actual allegations in the indictment, to suggest that some of them think Assange shouldn’t be prosecuted for conspiring to hack private companies, the language they included about the CFAA charge has led other outlets, picking up on this misleading language (along with the original error about the arrest date), to write at length about an indictment, with a more limited CFAA charge, that is not before Attorney General Merrick Garland. So maybe the NYT, Guardian, Le Monde, Der Spiegel, and El País know about the true extent of the CFAA charge, but by their vagueness, these five leading newspapers have contributed to overtly false claims by others about it.

Finally, the letter repeats WikiLeaks’ narrative about the changing DOJ views on Assange, presenting it as a binary between the “Obama-Biden” and Donald Trump Administrations.

The Obama-Biden administration, in office during the WikiLeaks publication in 2010, refrained from indicting Assange, explaining that they would have had to indict journalists from major news outlets too. Their position placed a premium on press freedom, despite its uncomfortable consequences. Under Donald Trump however, the position changed. The DoJ relied on an old law, the Espionage Act of 1917 (designed to prosecute potential spies during world war one), which has never been used to prosecute a publisher or broadcaster.

This is a story WikiLeaks likes to tell even while incessantly publicizing a a story that debunks it. It is based on a public quote — made in November 2013 by former DOJ spox, Matt Miller, who left DOJ in 2011, about why DOJ wouldn’t charge Assange. But a Yahoo story last year included former Counterintelligence head Bill Evanina’s description of how the US approach to WikiLeaks began to change in 2013, after Miller left DOJ but still during the Obama Administration, based on WikiLeaks’ role in helping Snowden flee.

That began to change in 2013, when Edward Snowden, a National Security Agency contractor, fled to Hong Kong with a massive trove of classified materials, some of which revealed that the U.S. government was illegally spying on Americans. WikiLeaks helped arrange Snowden’s escape to Russia from Hong Kong. A WikiLeaks editor also accompanied Snowden to Russia, staying with him during his 39-day enforced stay at a Moscow airport and living with him for three months after Russia granted Snowden asylum.

In the wake of the Snowden revelations, the Obama administration allowed the intelligence community to prioritize collection on WikiLeaks, according to Evanina, now the CEO of the Evanina Group.

Years earlier, CNN reported the same thing: that the US understanding of WikiLeaks began to change based on its role in helping Snowden to flee.

It should be unsurprising that the government’s approach to WikiLeaks changed after the outlet helped a former intelligence officer travel safely out of Hong Kong, because at least one media outlet made similar judgments about how that distinguishes WikiLeaks from journalism. Bart Gellman’s book described how lawyers for WaPo believed the journalists should not publish Snowden’s key to help him authenticate himself with foreign governments — basically, something else that would have helped him flee. Once Gellman understood what Snowden wanted, he realized it would make WaPo, “a knowing instrument of his flight from American law.” By his description, the lawyers implied Gellman and Laura Poitras might risk aid and abetting charges unless they refused a “direct attempt to enlist [them] in assisting him with his plans to approach foreign governments.” Like the US government, the WaPo judged in 2013 that helping Snowden obtain protection from other, potentially hostile, governments would legally go beyond journalism.

This is one reason clearly conveying the scope of the CFAA allegations is central to any credible commentary on the Assange case: because Assange’s exploitation of the Snowden assistance is an overt act charged in it. But five media outlets skip both the import of that act and its inclusion in the charges against Assange in a bid to influence the Biden Administration.

This WikiLeaks narrative also obscures one more step in the evolution of the understanding of Assange during the Obama administration, one that is more problematic for this letter, given that it would hope to persuade Attorney General Merrick Garland. Per the Yahoo article that WikiLeaks never tires of publicizing, the US government’s understanding of WikiLeaks changed still more when the outlet partnered with Russian intelligence on its 2016 hack-and-leak campaign.

Assange’s communication with the suspected operatives settled the matter for some U.S. officials. The events of 2016 “really crystallized” U.S. intelligence officials’ belief that the WikiLeaks founder “was acting in collusion with people who were using him to hurt the interests of the United States,” said [National Intelligence General Counsel Bob] Litt.

That’s important because, while the parts pertaining to WikiLeaks are almost entirely redacted, the SSCI Report on responses to the 2016 hack-and-leak makes it clear how central a role then-Homeland Security Advisor and current Deputy Attorney General Lisa Monaco played in the process. You’re writing a letter about which Garland would undoubtedly consult with Monaco. She knows that the gradual reassessment of WikiLeaks was no lightswitch that flipped with the inauguration of Donald Trump. Treating it as one provides one more basis on which DOJ could dismiss this letter. What changed wasn’t the administration: it was a series of WikiLeaks actions that increasingly overcame the “New York Times problem,” leading to expanded collection on Assange himself, leading to a different understanding of his actions.

Here’s why I find the sloppiness of this letter so frustrating.

I absolutely agree that, as charged, the Espionage Act charges against Assange are a dangerous precedent. That’s an argument that should be made soberly and credibly, particularly if made by leaders of the journalistic establishment.

I agree with the letter’s point that, “Obtaining and disclosing sensitive information when necessary in the public interest is a core part of the daily work of journalists,” (though these same publishers decided that disclosing the names of US and coalition sources was not in the public interest, and Assange’s privacy breach in doing so was the other basis by which Baraitser distinguished what Assange does from journalism).

But so is fact-checking. So is speaking accurately and with nuance.

If you’re going to write a letter that will be persuasive to the Attorney General, it would be useful to address the indictment and extradition request as it actually exists, not as it existed in 2019 or 2020 or 2021.

And if you’re going to speak with the moral authority of five leading newspapers defending the institution of journalism, you would do well to model the principles of journalism you claim to be defending.

As noted, these outlets corrected the date error after I inquired about the process by which this letter was drafted. I have gotten no on-the-record comments about the drafting of this letter in response.