At first, Paul Manafort claimed not to remember any August 2016 conversations with Roger Stone about impending WikiLeaks releases. He further speculated that all the interesting conversations about WikiLeaks releases must have happened in September, after he was off the campaign. And then, even in the same interview, he admitted that was wrong.

That’s in no way the most interesting disclosure in a September 27, 2018 Mueller interview with Trump’s campaign manager in the most recent BuzzFeed FOIA response. But given a detail revealed in the Roger Stone trial — not to mention the abundant evidence that Manafort was shading his testimony within the 302 itself — Manafort’s efforts to disclaim any knowledge of what Roger Stone was up to in August 2016 suggests an affirmative attempt to cover up his knowledge of and possibly involvement in Stone’s activities that month.

The partial view offered by a single 302

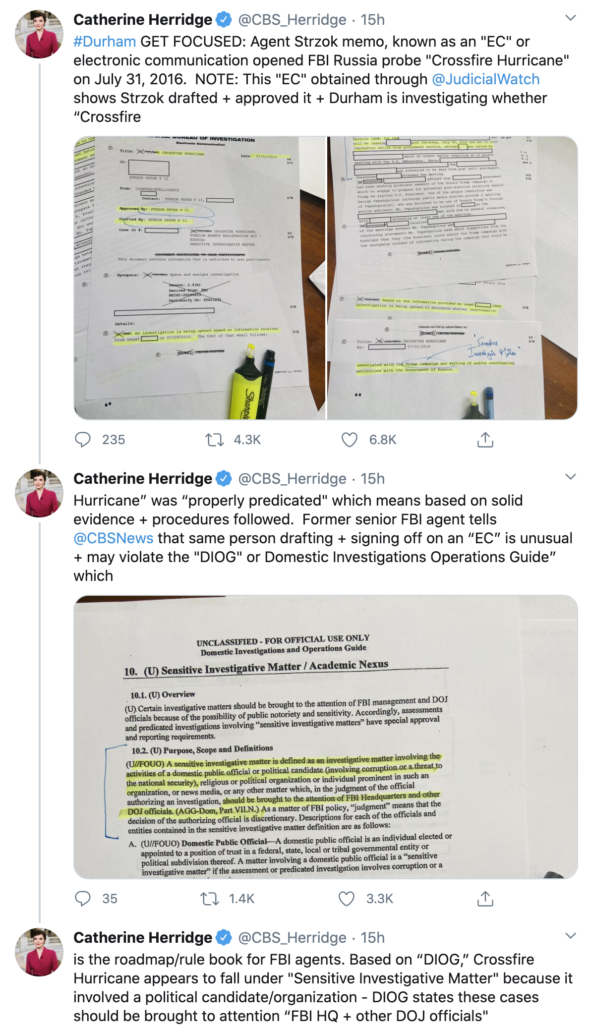

The 302 was released in the most recent BuzzFeed FOIA release, one that makes fewer redactions than prior ones. The 302 is almost entirely unredacted and focuses closely on Roger Stone. This interview was neither the first interview at which Manafort was asked about Stone, nor is it the only interview released that pertains to Stone. His identifiable interviews pertaining to Stone are:

But in the earlier released 302s, the Stone-related content was redacted either due to Stone’s trial, or because an investigation into Stone remained ongoing on March 2, 2020, with the 6th release, but appears to have ended after Barr intervened in Stone’s case. For example, the released version of the September 13 302 redacts Manafort’s description of a pre-June 12 conversation with Stone where he told Manafort that, “a source close to WikiLeaks had the emails from Clinton’s server;” I’ve collected what appears unredacted from that interview in the SSCI Report here.

In other words, this is the one 302, so far, that shows us what DOJ actually asked Manafort about during the period he pretended to be cooperating in fall 2018 but was in fact lying. We can’t assume this interview is the entirety of what DOJ asked Manafort for several reasons. First, what we can see here is iterative. What starts as one brief mention on September 12, expands on September 13 (one of the only interviews where Manafort is believed to tell the truth), appears unredacted in this September 27 interview. But we might expect the October 1 (and any other interviews where he was asked about Stone) to include more information.

In addition, there is abundant evidence that DOJ is preferentially releasing files where a witness (including but not limited to Steve Bannon, Sam Clovis, and KT McFarland) lied to protect Trump, while keeping later more truthful (and damning) testimony redacted.

More importantly, the only Manafort references to Stone in the Mueller Report are cited to his grand jury testimony (probably on November 2, 2018, but that is redacted):

- Manafort said Stone told him he was in contact with someone in contact with WikiLeaks. (fn 198)

- Manafort told Trump Stone had predicted the release, in response to which Trump told him to stay in touch with Stone. (fn 204)

- Manafort relayed the message to Stone, likely on July 25, 2016. (fn 205)

- Manafort told Stone he wanted to be kept apprised of developments with WikiLeaks and told Gates to stay in touch with Stone as well. (fn 206)

I suspect Manafort was asked about things in his grand jury appearance that he wasn’t asked about in 302s (which is what happened on other topics Manafort was lying about). That said, just one detail — the date on which Manafort probably relayed Trump’s request that Stone seek out more information on WikiLeaks — appears in the Mueller Report, but not here (though as I’ll show in a follow-up post, the government clearly withheld a great deal of what they knew from the Mueller Report).

Manafort claims Stone didn’t include his life-long friend in his cover-up

Let’s start with the end of the interview. It captures Paul Manafort’s claims not to have coordinated stories with Stone, even while Manafort himself was coordinating stories with everyone else and Stone was coordinating stories too.

Close to the end of the interview, interviewers got Manafort to confirm that he knew, at the time Stone claimed on October 11, 2016 that he had no advance knowledge of the Podesta email release, Stone’s claim was “inconsistent with what he told” Manafort earlier in 2016.

Investigators then proceeded to ask Manafort questions to figure out whether (he would admit whether) Stone had included him in the rat-fucker’s very elaborate cover-up. He did not.

First, they got a general denial.

Manafort and Stone did not have a conversation in which Stone said Manafort should not tell anyone about the timing of the Podesta emails. They did not talk about Stone running away from what Stone told Manafort.

At a time when Manafort was lying wildly about everything else (in significant part to protect Trump), Stone’s lifelong friend claimed that Stone had made less effort to coordinate a cover story with Manafort than he had with Randy Credico, with whom Stone had a far more troubled relationship.

Then investigators asked Manafort (who at this point had been in jail almost four months and whom prosecutors knew had been conducting covert communications from jail) whether he and Stone had spoken about the investigation in the past six months. We know from this affidavit that by May, Stone was frantically calling Andrew Miller and siccing a private investigator on Credico and another witness in an attempt to cover his actions up. But while Manafort admitted that he and Stone had spoken about the investigation, he claimed they had had no conversations about covering up Stone’s advance knowledge of the Podesta dump.

Stone said the Special Counsel’s Office was accusing him of effectively controlling the timing of the leaked Podesta emails. Manafort thought it was some time in May or June that Stone told him the Special Counsel’s office thought he had a role in the Podesta emails. Stone did not expressly remind or tell Manafort what he (Stone) knew about the emails. They did not discuss the fact that Stone did actually have advance knowledge of the Podesta emails.

Again, we’re to believe that at a time Stone was spinning wild cover stories with Jerome Corsi, whom Stone had only known two years, at a time Stone was hiring private investigators to intimidate witnesses to sustain his cover story, Stone wasn’t at the same time including his life-long friend Paul Manafort in his cover-up.

Then, immediately after having claimed he and Stone had no conversation about the Podesta emails, Manafort then described what sounds like an attempt on Stone’s part to minimize what he had done.

Stone said to Manafort that he was not the decision maker or the controller of the information. Stone said he may have had advance knowledge, but he was not the decision maker. Stone was making clear to Manafort that he did not control the emails or make decisions about them. Stone said he received information about the Podesta emails but was a conduit, not someone in a position to get them released.

After providing what was a really damning admission (one that might have some truth to it!), Manafort then disclaimed any useful information by professing to be confused about all of this (something he said about learning in advance about the July 22 dump).

Manafort was confused as to the various people and hacks. Manafort asked Stone to go through the narrative of Assange, Guccifer, the DNC hack, and Seth Rich so that Manafort could understand it.

Stone knew Manafort knew that Stone’s public statements were false, but Stone “confused” Manafort.

Seth Rich was, fundamentally, a cover story that Stone helped perpetuate among right wing propagandists to disclaim his early knowledge that Russia was responsible for the email hacks. Manafort’s claim of confusion might reflect that investigators indicated they knew he was lying. But it effectively is an admission that Stone tried to get Manafort to repeat the cover story Stone had adopted, in parallel with WikiLeaks.

Then Manafort made two more claims that were probably false:

Stone did not advise Manafort to punch back or discredit the Special Counsel’s Office. Stone did not raise any desire to respond to the Special Counsel’s Office investigation by planting media stories.

Manafort was not aware of any attempts on Stone’s part to contact Manafort after Manafort was incarcerated.

Again, we’re to believe that Stone was working with everyone else he knew to push back on Mueller, but did not with Manafort (even while Manafort was having the same kinds of communications with Sean Hannity and others).

Most of the rest of the interview consists of Manafort trying to suggest that Stone had worked with Bannon on the Podesta emails (a claim he made earlier, as I’ll return to), effectively pawning off any coordination Stone did with the campaign to a time after Manafort left it.

Stone did not tell Manafort whether he passed the Podesta email information to anyone else on the campaign or associates with the campaign. Manafort speculated Stone may have passed information to Bannon, since Stone and Bannon had a relationship.

[snip]

Manafort thought Stone gave messaging ideas to Bannon, but did not think Stone was a source of information for Bannon.

Not only does this comment pawn any guilt onto Bannon, but it protects Trump from involvement he had in July and August.

Manafort’s evolving denials of any involvement in Stone’s activities

So that’s how the interview ends, with a Manafort effort to pawn off any guilt onto Bannon even while protecting Trump and others close to him, even after admitting that he and Stone had some conversation where Stone talked him through Assange, Guccifer, DNC, and Seth Rich.

Much earlier in the interview, Manafort confirmed some damning things that other witnesses had only hinted at. Here’s a summary of most of them (I’ll show how Manafort disproved his own claims about the Podesta emails next). Below I’ll show how for each damning admission, Manafort disclaimed substantive three-way coordination between him, Stone, and Trump, some of which he had already admitted to in his September 13 interview.

- Late May to early June: He had a conversation with Stone before Julian Assange said on June 12, 2016 WikiLeaks was publishing Hillary’s emails. In late May or early June, Stone said someone had good information that WikiLeaks had access to the emails on Clinton’s servers, which Manafort took to be a self-serving comment.

- After June 12: After Assange’s June 12 presser, Trump could and did start incorporating Hillary’s emails into his speeches, based on the premise that “if WikiLeaks had them, it was possible a foreign adversary did too.” Manafort said that Stone did not know what the emails were at that time.

- Between June 12 and the release of the DNC emails — a black hole: “Manafort wasn’t really interested until something was released” … “Manafort used Caputo to keep track of Stone, but by around June 15, 2016, Caputo left the campaign” … “Stone ‘went dark’ on WikiLeaks in late June.”

- Before July 21: Manafort and Stone had breakfast at the RNC where Stone clearly told Manafort stuff that anticipated the DNC email release, but about which Manafort made lame excuses.

- After the July 22 dump: Manafort gives credit to Stone for the release, and Trump tells Manafort that Stone should “stay on top of [the WikiLeaks dump].”

- August: While Manafort admits he raised the emails at a Monday Meeting, he claims all the interesting conversations about the emails must have happened after he left.

For each of these fairly damning revelations, Manafort offered logically inconsistent claims that he was out of the loop of any communications Stone had with Trump, as follows.

1 Manafort claims he didn’t tell Trump but would have known if Stone did

Manafort said Stone brought this up because of something Trump had said, but Manafort didn’t share the information with Trump and asked Stone not to tell Trump himself because he wanted to avoid a “fire drill” to go chase the emails down. Manafort considered the possibility Stone told Trump in spite of Manafort’s request he not do so, but claimed he would have known had Stone had done so.

Manafort asked Stone not to convey it to Trump, and Stone agreed. Manafort thought Stone would keep his word, but he was not convinced he would. Manafort did not have any indication whether or not Stone told Trump regardless of Manafort’s request. Manafort did not have a contemporaneous memory that Stone had told Trump about the emails, because he did not recall a conversation with Trump about it back then, which he would have expected if Trump knew.

In his September 13 interview, Manafort had already admitted that he believed Stone would have told Trump anyway because he ”wanted the credit for knowing in advance.”

2 Manafort admits he did talk to Trump after June 12 and suggests indirectly that he served as go-between the two

Even though Manafort had claimed not to have (and not wanted to have) discussed Stone’s predictions prior to Assange’s June 12 presser, Manafort did admit to discussing the emails after Assange’s presser. Manafort explained the difference between before and after Assange’s presser (and the reason why he was willing to discuss it with Trump) this way:

Manafort said there was no real fire drill after June 12, 2016 because the information was already out there. The fire drill would have been if Stone had been the only one saying it and Trump wanted more.

But Manafort then says some things about the conversations with Trump. The easiest way to make them cohere chronologically is if Trump did ask Manafort to find out more. I’ve rearranged Manafort’s claims, numbering the order in which he presented them.

- Manafort thought he spoke to Trump and said Stone had it right, and that Trump was happy and looked forward to what WikiLeaks had. Trump asked Manafort if Stone knew what was in the emails. [2]

- Manafort and Stone spoke after the June 12, 2016 article and Manafort said he [Manafort] was looking forward to what came out and also asked Stone whether he knew what Assange had. [1]

- Manafort believed Stone told him he was working to find out what the emails included. [4]

- Manafort told [Trump] no [Stone didn’t know what was in the emails] [3]

This may be a minor point, but Manafort’s description is inconsistent with there not being a conversation with Trump before June 12. That’s true because of the way he told Trump “Stone had it right,” reflecting prior knowledge, but also the way he reorders what happened to claim that he didn’t do what he said he had been afraid of having to do before June 12, run a fire drill.

This is the first time of two times that Manafort, in response to a question about whether he talked to someone whose name was redacted about WikiLeaks, he responded that that was “Miller’s” job (both Stephen and Jason were involved in WikiLeaks response and it’s unclear if an earlier redaction makes it clear which one he was talking about). That may be an effort to cover up Jared Kushner’s involvement (at trial, the government introduced evidence that Stone reached out to Kushner, and in the plea breach discussions the government accused Manafort of protecting someone who is almost certainly Kushner).

3 Manafort claims he wasn’t interested, Stone didn’t say anything, and doesn’t address discussions with Trump

Since Manafort claims not to have spoken to Stone about emails in the period when Guccifer 2.0 was releasing material but WikiLeaks was not, he doesn’t address whether he told Trump at all.

Stone “went dark” on WikiLeaks in late June. Manafort initially thought Stone’s advance knowledge was more of a guess.

As the SSCI Report makes clear, however, Manafort had at least six phone conversations that month, including these four:

- June 4

- June 12

- June 20

- June 23

4 Manafort tells a bullshit story about a breakfast he had that Morgan Pehme caught on tape

Early on in the interview, Manafort disclaimed June interest in emails by saying, “Manafort did not get really interested until something was released, which happened between the two conventions.” In the same paragraph, he is recorded as saying, “at that point [before something was released], Manafort could not rely on Assange.” The comment doesn’t make sense in any case, given that Guccifer 2.0 was releasing emails (which Manafort disclaims by saying they didn’t speak about emails). But in trying to discuss a breakfast captured on video, he virtually concedes Stone gave him detailed information before the DNC dump.

Manafort described a breakfast meeting he and Stone had that (he admits in the interview) had been partly caught on tape by the team making Get Me Roger Stone.

Manafort discussed a breakfast he had with Stone during the RNC, which was visible briefly in the “Get Me Roger Stone” documentary. They discussed convention speeches at that breakfast. Stone also complained about Ted Cruz. They discussed the DNC, because Manafort planned to go and give some speeches during it. WikiLeaks would have come up in that breakfast in reference to what they would be doing and how the campaign would use it. Manafort did not recall whether Stone said he knew when the WikiLeaks information was going to come out. They discussed Clinton’s server, WikiLeaks, and the DNC hack. They focused more on the DNC hack because it had current political value at the time. Manafort summarized the breakfast as a discussion about the DNC hack, when WikiLeaks planned to release the material, Manafort trying to understand the attack lines that would be used during the DNC and in the month of August, and the thematic strategy for the campaign.

Stone “went dark” on WikiLeaks in late June. Manafort initially thought Stone’s advance knowledge was more of a guess. It was not until the information about Debbie Wasserman-Schultz came out that Manafort realized the real value of the information. Stone did not tell Manafort the Wasserman-Schultz information was coming out in advance, but he was pleased when it did. That was the first time Manafort thought Stone’s connection to WikiLeaks was real.

According to emails released at trial, during the spring of 2018 (and well before) Randy Credico and Stone kept coming back to whether or not Morgan Pehme, one of the directors of Get Me Roger Stone, had “folded” or was lying. The film team had outtakes that showed more of what transpired at events they had filmed. So even Credico and Stone seemed worried about what having a film team travel around filming Trump’s rat-fucker might have seen while he was trying to steal the election.

Manafort (who, remember, would go on to disclaim having talked about cover stories with Stone) seems to have been aware of the risk, too.

This explanation from Manafort about this breakfast reveals one reason why. In the same breath as saying that Stone had gone dark in the period between Julian Assange’s June 12 interview and the actual release of the emails, Manafort got caught on film talking about it as an active thing. I have suggested that Stone met someone at the RNC who told him the emails were about to drop at a meeting that Andrew Miller would have scheduled. So it’s possible that this meeting happened in the wake of the one where Stone learned the drop was imminent. Manafort provides explanations that aren’t plausible given his other testimony, and comes close to admitting that the conversation reflected foreknowledge of the July 22 dump, which (as Manafort had already noted) came after the RNC ended.

5 Manafort disclaims any participation in the discussions between Stone and Trump

Manafort’s apparent message about what happened immediately after the DNC dump — which showed up in Stone’s trial as Trump ordering Manafort and Gates to get Stone to find out more — is that both he and Trump compartmentalized any discussions that happened about what came next.

The timeline he describes looks like this (though again, Manafort jumbled it a bit in the telling):

- Before the weekend (and so either when the emails dropped or before): Manafort told Stone he was impressed and would be using it “the upcoming weekend in Philadelphia” and asked for more information, in response to which Stone did not specify.

- After the July 22 dump: Manafort talked to Trump first (he would have had to have already spoken with Stone, though).

- At the end of July 22: a possible different conversation with Trump and Reince Priebus.

- Later in the weekend, probably July 23: Manafort “raised with” Trump that Stone had predicted it and Trump responded “that Stone should stay on top of it.”

- July 24: Priebus and Manafort had talking points on the dump.

Then, as part of two paragraphs describing Manafort having a conversation that included the same things as the conversation he had before the weekend with Stone but is portrayed as after July 24, Manafort claims all of this was compartmentalized.

Manafort did not tell Stone specifically that Trump had asked that he stay on top of it. He would have just told him to stay on top of it. Manafort did not way to get into a cycle with Stone where Stone used him as an errand boy to get to Trump.

Manafort did not have any indication Trump heard from Stone directly, but he thought he would have. Trump would not have told Manafort if he was talking to Stone. Trump compartmentalized; it was just the way he was.

Manafort told Stone it was good stuff and to keep him posted, and Stone offered no indication he knew any more specifics.

Effectively, Manafort suggests both that Trump kept things with Stone compartmentalized — it was just the way he was! — which may conflict with his first explanation, that he’d be told of any discussions (in his September 13 testimony, he said he assumed they did speak before the DNC dump). In any case, Manafort also claims to be compartmentalizing himself, withholding from Stone the fact that Trump ordered Manafort to reach out.

I’ll come back to this.

6 Manafort admits certain things happened in August but claims he had no role

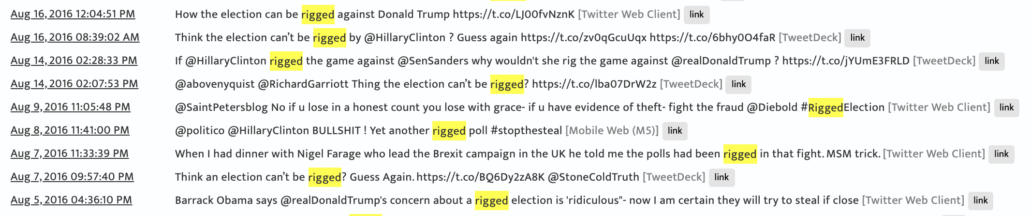

The government had two very specific questions for Manafort about August. First, did he speak to Stone about his August 8 speech in which he said there’d be more from WikiLeaks releases (remember, there were a whole series of such claims, but the government apparently only asked about the August 8 one). Manafort claimed he did not.

Manafort and Stone did not discuss Stone’s August 8, 2016 in which he said more was coming from WikiLeaks. Manafort recalled from the press coverage that Stone was confident more was coming in the fall. Stone never told Manafort he was dealing with Assange directly. Manafort assumed Stone had a contact of some sort. Stone’s August 8, 2016 comment was not out of character for Stone.

In other words, Manafort admits knowing about Stone’s comment (either this specific one or generally), but sourced it to the press, not Stone (or Trump). And though he admits that such boasts were normal for Stone, he seems to concede he nevertheless noticed them — in the press.

Investigators also asked Manafort, twice, about how the WikiLeaks releases came up at the Monday Morning meetings involving the family (they obviously had a specific one that occurred in the wake of the DNC release in mind). Over the course of an extended discussion, Manafort does admit it came up but suggests — in spite of the fact that Trump was “fixated on the topic” — that the discussion of Stone’s advance knowledge amounted to little more than, “that sounds like Roger.”

[After a claim that Manafort would later disprove that he had no conversations with Stone about WikiLeaks] Manafort was not certain when the next Monday morning meeting was, but it was either July 31 or August 7, but thought it was probably August 7, 2016. Manafort was sure WikiLeaks was raised and the discussion was about how useful the information was and when they could expect the next dump. Manafort thought it was probably a topic of many conversations. Trump was fixated on it.

[3 paragraphs in which Manafort concedes that someone at RNC was in the loop and claims that any substantive discussions happened after he left and then claims, probably for a second time, that “Miller” (which could be either Jason or Stephen) was in charge of those issues, so Kushner wouldn’t have been)]

The Monday morning family meeting has a two-fold agenda. One they discussed relevant “gossip” for the campaign. [Manafort tells anecdote about Michael Cohen catching Lewandowski leaking.] The meeting also covered scheduling. Manafort would lay out Trump’s travel schedule and they discussed how to integrate the family into events. Manafort said that when WikiLeaks was in the news, it would have been covered in the gossip section of the meeting. He remembered a discussion in which people said the Wasserman-Schultz stuff was helpful because it allowed Trump to say Clinton rigged the election against Bernie Sanders.

Manafort was sure he mentioned in a Monday meeting that Stone predicted the WikiLeaks dump. The reaction was something along the lines of “that sounds like Roger” and wondering about what else was coming. Stone had been putting it out there, but Manafort did not know if the family knew Stone had predicted it in advance.

Family meetings were attended by Manafort, Gates, Trump, Jr., Eric Trump, Hope Hicks, and sometimes Jared Kushner and Ivanka Trump.

So Manafort admits being aware that Stone was wandering around claiming to know more was coming and that more was coming came up at a family meeting. These events happened on July 31, at the latest, per his testimony. But then he goes on to claim that he doesn’t remember any conversations in August with Stone about it.

Manafort did not recall any specific conversations in August 2016 with Stone about WikiLeaks.

As he did later in the interview, Manafort (who admitted ongoing ties with the campaign in his September 13 interview) suggested the good stuff happened after he left.

Manafort thought the campaign would have started to more aggressively look for more information from WikiLeaks in late August, and by that time, he was gone.

Poof! On September 27, 2018, at a time when Trump’s former campaign manager was pretending to cooperate, probably in an effort to learn what prosecutors knew and buy a pardon, Paul Manafort claimed that he did not have any memorable conversation with Roger Stone about WikiLeaks in the entire month of August.

Manafort disproves his own claims about August

Manafort then goes on to admit to at least one and probably two conversations that he remembered specifically that pertained to WikiLeaks.

Manafort was sure he had at least two conversations with Stone prior to the October 7, 2016 leak of John Podesta’s emails.

In the one conversation between Stone and Manafort, Stone told Manafort “you got fucked.” Stone’s comment related to the fact that Manafort had been fired. The conversation was either the day Manafort left the campaign or the day after.

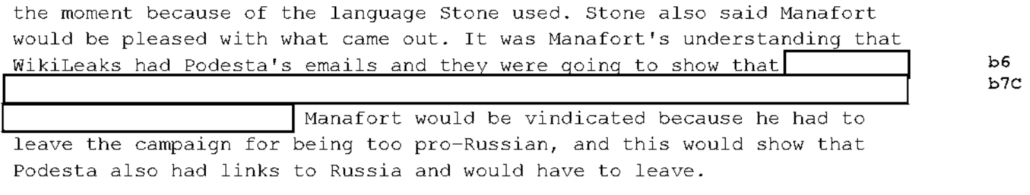

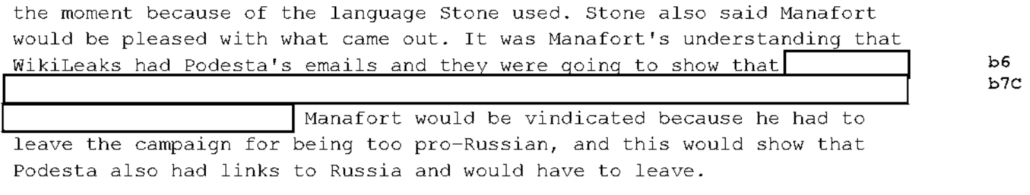

In the other conversation, Stone told Manafort that there would be a WikiLeaks drop of emails with Podesta, and that Podesta would be “in the barrel” and Manafort would be vindicated. Manafort had a clear memory of the moment because of the language Stone used. Stone also said Manafort would be pleased with what came out. It was Manafort’s understanding that WikiLeaks had Podesta’s emails and they were going to show that [redacted] Manafort would be vindicated because he had to leave the campaign for being too pro-Russian, and this would show that Podesta also had links to Russia and would have to leave.

Manafort’s best recollection was the “barrel” conversation was before he got on the boat the week of August 28, 2016.

The first of these conversations, of course, may not have to do with Podesta. Except that — coming as it did the day on or the day after he left — it means it’s the around same day, August 15, 2016 that Stone tweeted about Hillary’s campaign manager for the first time ever.

@JohnPodesta makes @PaulManafort look like St. Thomas Aquinas Where is the @NewYorkTimes?

When Manafort got forced out of the campaign, Stone responded publicly in terms of John Podesta, whose emails he already knew WikiLeaks would be dropping.

The second conversation, which in this interview Manafort remembers clearly took place before he got on a yacht the week of August 28 (in the September 13 interview he placed it later), Stone said the same thing he said in his famous Tweet. It’ll soon be Podesta’s time in the barrel. Manafort claims to remember that “time in the barrel” language, but not Stone’s tweet. Manafort’s testimony seems to refute Stone’s cover stories about the tweet (here, Stone specifically describes it in term of just John Podesta). More importantly, Manafort’s testimony included details, a specific description of what Stone knew the Podesta emails to be released more than two months later would include, that would allow us to determine whether — as abundant evident suggests — Stone got advanced notice if not copies of materials relating to Joule Holdings in August 2016.

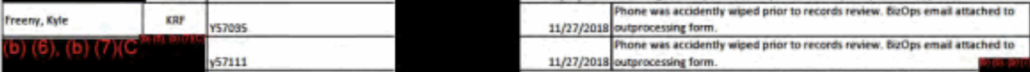

Except DOJ redacted that detail, which might reveal after 4 years, whether John Podesta’s suspicions that Roger Stone got his emails in advance were correct.

DOJ did so, based on the b6, b7C exemptions, to protect John Podesta’s privacy.

Investigators don’t ask how Stone proposed “to save Trump’s ass”

So Manafort, at first, obscured at least one really damning conversation in August, when Stone told him stuff that Stone would later spend years trying to cover up.

But there is almost certainly another.

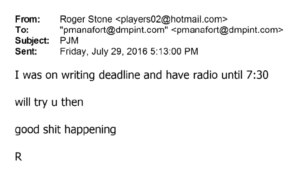

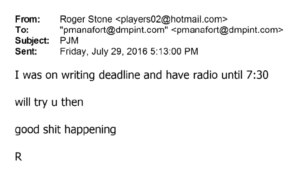

Admittedly, Manafort was asked about calls in August, not calls after the DNC drop. So this email boasting of “good shit happening” would not be included.

Nor would the 68 minute phone call they had the next morning, the longest call they had that year.

Records reflect one-minute calls (suggesting no connection) between Stone and Manafort on July 28 and 29.1545 On July 29, Stone messaged Manafort about finding a time for the two of them to communicate, writing that there was “good shit happening.”1546 The back-a~d-forth between Stone and Manafort ultimately culminated in a 68-minute call on July 30, the longest call between the two of which the Committee is aware.1547

But Manafort did respond to an email offering “an idea to save Trump’s ass” by calling Stone. And that was in August.

Stone spoke by phone with Gates that night, and then called Manafort the next morning, but appeared unable to connect. 1559 Shortly after placing that call, Stone emailed Manafort with the subject line “I have an idea” and with the message text “to save Trump’s ass.”1560 Later that morning, Manafort called Stone back, and Stone tried to reach Gates again that afternoon. 1561

At trial, the prosecution included both exchanges among its examples of times Roger Stone contacted people from the Trump campaign about WikiLeaks.

Stone’s lawyers got FBI Agent Michelle Taylor to admit she had no idea what happened after even the first email.

Q. Tab 8, Exhibit 24, this is from Roger Stone to Paul Manafort, correct?

A. Yes.

Q. And the date of that?

A. This is an email dated July 29th, 2016.

Q. Do you know when the Republican National Convention occurred in 2016?

A. I do. I may have the dates a little off, but it was before this, July 19th to 21st maybe.

Q. All right, and do you know what, if anything, happened as a result of this email?

A. Do I know what happened as a result of this email?

Q. Yes.

A. No.

In closing, Jonathan Kravis asserted that the context proved this was about WikiLeaks.

On August 3rd, 2016, Stone writes to Manafort: “I have an idea to save Trump’s ass. Call me please.” What is Stone’s idea to save Trump’s ass? It’s to use the information about WikiLeaks releases that he just got from Jerome Corsi. How do know that’s what he had in mind; because that’s exactly what he did. As you just saw, just days after Stone sends this email to Paul Manafort, “I have an idea to save Trump’s ass,” he goes out on TV, on conference calls and starts plotting this information that he’s getting from Corsi: WikiLeaks has more stuff coming out, it’s really bad for Hillary Clinton.

Certainly, the government seems to have confidence that both those calls did pertain to WikiLeaks.

But they didn’t ask that question in a process they had reason to believe would be reported back to Donald Trump.

Paul Manafort’s answers in this interview appear to be a cover story, admitting some damning stuff, all while claiming there weren’t communications — particularly in August — we know there were. Which says Stone and Manafort (and, with the closure of these investigations, Bill Barr) are covering up something even more damning that the specific details of upcoming email dirt on John Podesta they’re withholding to protect John Podesta.