The normally very rigorous Thomas Brewster has a piece purporting to fact-check Sheryl Sandberg’s claim, made days after the January 6 insurrection, that the insurrection wasn’t organized on Facebook.

“I think these events were largely organized on platforms that don’t have our abilities to stop hate and don’t have our standards and don’t have our transparency,” said Sheryl Sandberg, Facebook chief operating officer, shortly after the Capitol Hill riots on January 6.

The piece has led both bad faith and good faith actors to grasp on the story to claim that Facebook is responsible for the violence.

Brewster purports to measure that by seeing how many mentions appear in the charging documents for the 223 people included on GWU’s list of arrestees.

But a few paragraphs later, Brewster admits he’s not measuring on what platform the riot was organized, but instead which was most popular among rioters.

Whilst the data doesn’t show definitively what app was the most popular amongst rioters, it does strongly indicate Facebook was rioters’ the preferred platform.

Even that is not proven (though it may well prove to be true), but obviously which platform is most used among rioters to boast about the riot is a very different question than on which platform (if any) the insurrection was organized.

Here’s why:

- At least half the existing affidavits are a measure of which riot attendees were most likely to be outed and how

- Expect parallel construction

- There are a lot of dangerous rioters who’ve not yet been charged

- The currently accused in no way represent all the known people who might be considered organizers of the riot or the larger operation

- The existing affidavits are no measure of what platforms actual organizers used to organize

At least half the existing affidavits are a measure of which riot attendees were most likely to be outed and how

The police made just a handful of arrests on January 6, with the biggest component being curfew violators who did not even provably enter the Capitol (and so those non-federal cases should not be included in the analysis of rioters, as Brewster did).

In the four and a half weeks since the riot, the cops have engaged in a kind of triage, arresting those whom they could easily identify and then, over time, prioritizing those who — from video evidence of the insurrection — appeared to have committed more dangerous crimes. That means in the days after the insurrection, arrests largely focused on the people who appeared the most outlandishly stupid in videos, those whose own social networks of family, work acquaintances, and high school friends disapproved of their participation in the riot and so called the FBI with a tip, or those who identified themselves in media interviews (which often led to family, work acquaintances, and high school friends to then alert the FBI).

To understand the affidavits, it’s important to realize that any person who entered the Capitol without a legitimate purpose on January 6 (that includes a number of people who videoed the event but had no media credentials) were committing two crimes, both tied to it being the Capitol. So all the FBI would need to charge someone is to prove that they entered the building.

About half the current arrestees were charged with just these trespassing crimes, yet many of these people were among the first arrested. These people are in no way the organizers of the riot, and many of them are just Trump supporters who were caught up in the crowd. Some even credibly described trying to de-escalate the situation (including one such guy who got arrested because he had the misfortunate to show up in videos of the guy who stole Pelosi’s lectern).

The measure of how these people were arrested is quite often a measure of the fact that they shared their memories of the day or were caught by others who did. And to the extent that this happened on Facebook, it likely happened because Facebook is the platform where people have their broadest social networks, making it more likely that a lot of people who don’t sympathize with the riot would have witnessed social media content talking about it. Facebook is where ardent Trump supporters still share networks with people who vehemently oppose him.

In other words, in this initial arrest push, the people who bragged on Facebook were among the most likely to be arrested precisely because the network includes a broader range of viewpoints. It’s a measure of reach — and the political diversity of that reach — and not a measure of the centrality of the platform to the planning or violence.

Expect parallel construction

As noted, in the weeks since the insurrection, some agents at the FBI have obviously shifted to a reverse approach: rather than arresting those against whom tips came in from aggrieved ex-wives and people who were owed money, the FBI started to identify which rioters were the most dangerous and prioritize figuring out who they were.

One type of more dangerous rioter would be those with institutional ties that lead the FBI to believe there might be something more going on. But these are just arrest affidavits, which the FBI is acutely aware will be publicly scrutinized. As every single one of them say, they don’t reflect the totality that an Agent might know about the person. And in those cases, we should expect the FBI to parallel construct what they know about people and how they came to know it.

Social media is a wonderful way to do that.

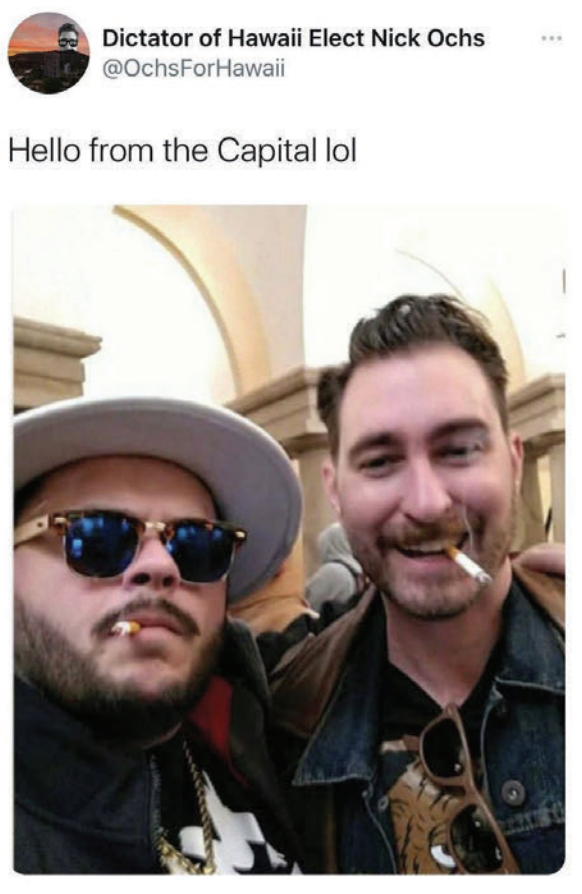

And it does seem that the FBI relied on social media to establish probable cause for such people. Take the Lebanese-born woman who started engaging in the 3% community in November, which the FBI cites to Facebook. Or consider how the FBI pretends they did not know who Nick DeCarlo was until he showed up in Nick Ochs’ Twitter feed. Both rely on social media (in the latter case, one piece of evidence is something researchers found on Telegram and posted on Twitter, and so should be chalked up in the “uses Telegram” column).

But measuring how the FBI parallel constructed other knowledge is not a measure of what social media platforms people primarily use.

There are a lot of potentially dangerous rioters who’ve not yet been charged

As noted, one way the FBI shifted focus after the initial arrests of people identified by their disapproving family members was by identifying people involved in assaults — first of officers (designated by AFO), and then the media (designated by AOM) — and trying to identify them, in part through the use of Wanted posters (BOLO).

To date, the FBI has released 223 BOLOs, of which 40 precede the shift of focus to those involved in assault (and so include people who caught attention for another reason, such as the use of a Confederate or Nazi imagery). The FBI has arrested around 35 people identified in BOLOs, thus leaving around 190 people that the FBI has identified to be of particular interest based off video images, that they have not yet arrested.

For what it’s worth, I suspect that the FBI has identified a goodly number of these people, and may even have sealed complaints against some of them but is holding off on an arrest to gather more evidence. That is, they can arrest them now, but would prefer not to until they shore up their case. In a number of cases where people were identified off of BOLOs, the people turned themselves into the FBI but denied any physical contact was anything but a love tap (here’s one example, but there are others), potentially making it harder to prosecute for the violence.

If and when these people are identified, they may well prove to have used Facebook. But thus far, this group of people has shown better operational security and (unsurprisingly) a greater likelihood to flee or to destroy evidence.

But whatever their Facebook use, when counting the numbers of the 800 people who committed a trespass crime on January 6 by entering the Capitol, of which 200 have been arrested, it’s worth noting that almost another 200 — some of the greatest concern — have not been provably identified by bragging Facebook posts yet.

The currently accused in no way represent all the known people who might be considered organizers of the riot or the larger operation

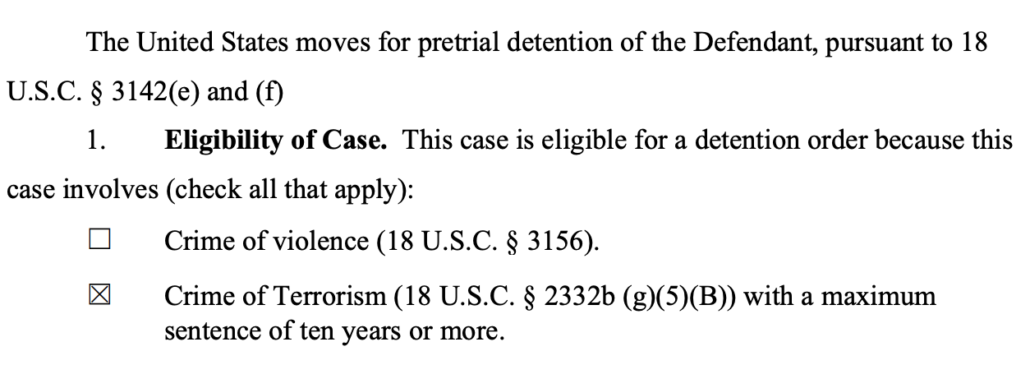

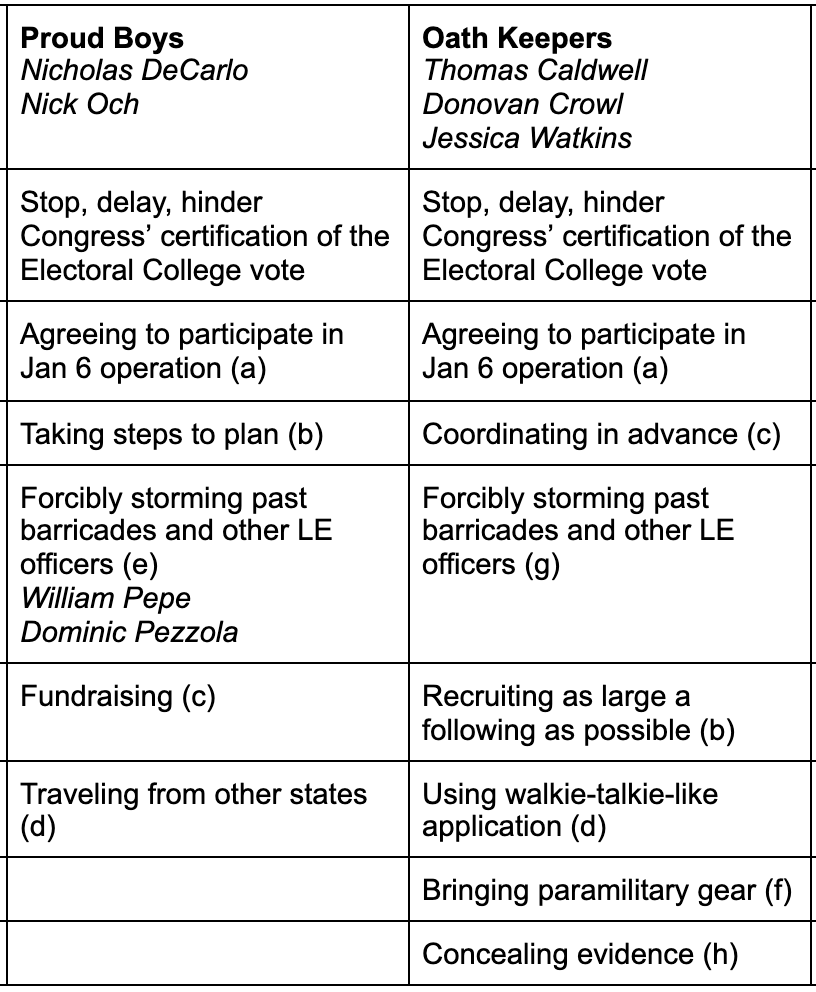

Thus far, the government has filed the bare outlines of conspiracy charges against both the Oath Keepers (who spoke of a plan they had trained for) and the Proud Boys (who moved in obviously coordinated fashion communicating via radio on January 6). But those conspiracy charges currently include just three and two people, respectively (with a sub-conspiracy charged against two more Proud Boys).

According to claims quoted in charging documents, there were anywhere from 30 to 65 Oath Keepers involved in the riot (including a busload from North Carolina). There are at least three other key Proud Boys that have not been arrested for the riot (Enrique Tarrio, of course, was arrested days earlier for a different racist attack), and about half of those that have were charged with just the trespassing crimes.

In general, these people are not currently identified in BOLO posters.

In other words, this is a set of people — perhaps another 40 on top of the 190 outstanding BOLO figures — that the FBI likely considers key suspects.

And that’s just the organizers of the riot. That doesn’t include James Sullivan, who appears to have been in communication — via text — with Rudy Giuliani. It doesn’t include people like Ali Alexander and Rudy and possibly Roger Stone who would tie the riot to the larger effort to delay the vote (which is the object of both the Oath Keeper and Proud Boys conspiracy). We know from Stone’s prosecution, at least, that he was de-platformed long ago and learned to use encrypted apps by August 2016.

In any case, before you can make claims about what platforms were used to organize the insurrection, you first need to identify the universe of people believed to have organized it. Right now, perhaps as few as 20 of the 200 people who’ve been arrested should be considered leaders of it, and there are probably at least another 40 who might be considered organizers of the riot itself who have not been arrested yet.

The existing affidavits are no measure of what platforms actual organizers used to organize

To be sure, both of the groups identified in conspiracies (and Three Percenters) made use of Facebook. As Brewster cited, accused Oath Keeper conspirator Thomas Caldwell posted updates to Facebook during the siege, and the co-conspirators did use Facebook to communicate both publicly and privately before the event. Among those referencing the Proud Boys in affidavits, Andrew Ryan Bennett uploaded video to Facebook, Gabriel Garcia uploaded video to Facebook, and Daniel Goodwin used Instagram and Twitter. As noted above, Nick Ochs had a campaign Twitter account.

But some of the more substantive public communications from both groups, including important communications from before the riot, was posted on Parler. And both groups used other means — Zello for the Oath Keepers and radios for the Proud Boys — to communicate operationally during the day.

With the Proud Boys, in particular, Facebook and Twitter have long tried to exclude them from the platform, both because their speech violated platform guidelines but also because after expulsion the group tried to bypass that expulsion.

Importantly, aside from some quotations from Jessica Watkins’ Zello account and those Facebook messages, the FBI hasn’t shown what it has of operational communications between these groups, and it’s unlikely to do so, either, until trial. The FBI is not going to share how much it knows (if anything) about the operational contacts of these groups until it has to. Which makes any conclusions drawn from what it is willing to show of questionable validity.

Don’t get me wrong: I’m happy to argue that Sheryl Sandberg is one of a number of Facebook executives who should be ousted. I agree that Facebook has fostered right wing violence, not least with the settings of its algorithms (which is the opposite of what Glenn Greenwald wants the Facebook problem to be). Because it has such wide breadth, it is a platform where people not already radicalized might get swept up in disinformation.

But I know of little valid evidence yet about Facebook’s role in organizing the insurrection, nor is there likely to be conclusive evidence for some time yet.

Update: Changed language to describe Tarrio’s alleged vandalism of a traditionally black church to make it clear he is not accused of assaulting another person.