Hunter Biden[‘s “Laptop”] Goes to SCOTUS: How Judge Doughty Helped China and Iran Attack the US

Hunter Biden is going to SCOTUS!!!

Or rather, the “Hunter Biden” “laptop” is.

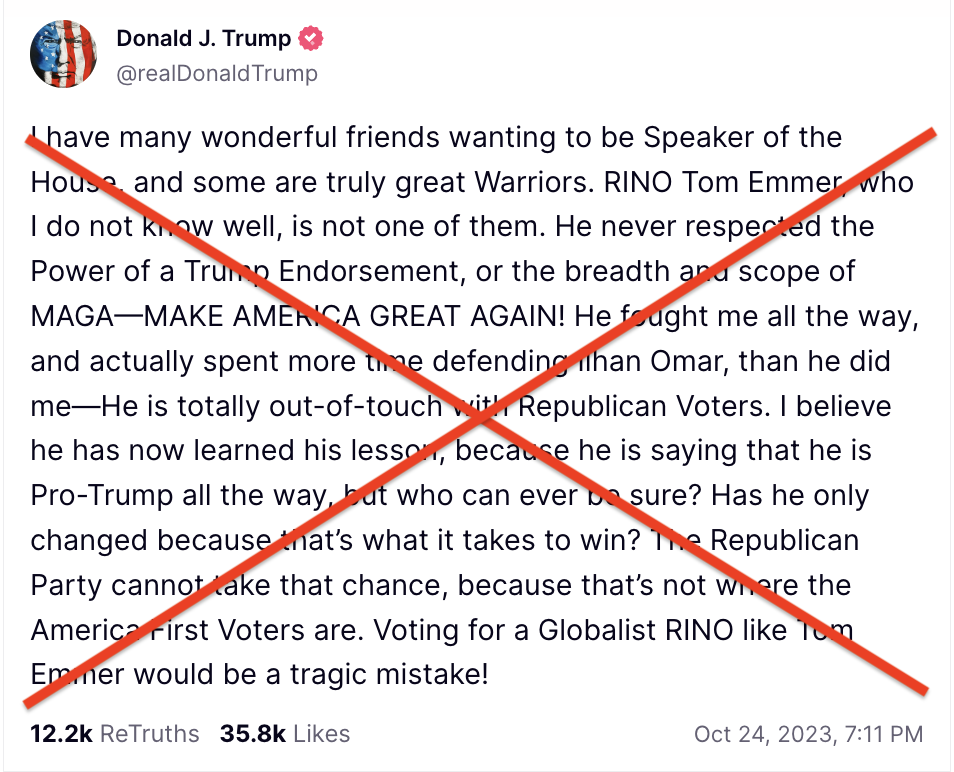

Last Friday, SCOTUS granted a stay and certiori for DOJ’s appeal of the Missouri v. Biden case, a right wing lawsuit claiming that the government has forced social media companies to “censor” right wingers (Terry Doughty opinion; 5th Circuit Opinion). While much of the lawsuit focuses on efforts, including those starting under a guy named Trump, to help social media companies limit COVID-related disinformation (Surgeon General Vivek Murthy is the lead appellant), a key part of the claim that the government has coerced social media companies pertains to the FBI.

The Fifth Circuit opinion upholding parts of Judge Doughty’s opinion admitted that, “we cannot say that the FBI’s messages were plainly threatening in tone or manner” but suggested nevertheless that they “’might be inherently coercive if sent by . . . [a] law enforcement officer’” anyway.

Because the people pushing this suit, including now-Missouri Senator Eric Schmitt and now-Louisiana Governor-elect Jeff Landry, are nuts, the “Hunter Biden” “laptop” has come to embody that coercion. The Fifth Circuit adopted that focus (and several inaccurate claims about it) as well. And, in turn, Sam Alito included that focus, citing the Fifth Circuit, in his snotty dissent.

This case began when two States, Missouri and Louisiana, and various private parties filed suit alleging that popular social media companies had either blocked their use of the companies’ platforms or had downgraded their posts on a host of controversial subjects, including “the COVID–19 lab leak theory, pandemic lockdowns, vaccine side effects, election fraud, and the Hunter Biden laptop story.” Id., at *1. According to the plaintiffs, Federal Government officials “were the ones pulling the strings,” that is, these officials “‘coerced, threatened, and pressured [the] social-media platforms to censor [them].’”

This argument, as currently framed, is about whether Judge Doughty properly enjoined the FBI from certain kinds of contacts with social media companies because of the “Hunter Biden” “laptop.”

The Injunction

The injunction on the FBI, imposed largely because of right wing beliefs about the “Hunter Biden” “laptop,” may also explain why three Republican justices granted cert. The prohibition on certain kind of FBI contacts with social media companies may be among the most urgent injury the US government faces under the injunction. That’s partly because Judge Doughty specifically enjoined Elvis Chan, the Assistant Special Agent in Charge of cybersecurity investigations out of San Francisco, and so a key person involved in preventing and responding to cyberattacks targeting or using the infrastructure of social media companies located in Silicon Valley.

Alito’s dissent claims that DOJ only cared about Joe Biden’s bully pulpit, which is not included in the injunction. But in its appeal, DOJ noted that, as written, the injunction might lead the FBI to hesitate before alerting social media companies to potentially harmful content.

And given the court’s suggestion that any request from a law-enforcement agency is inherently coercive, see id. at 232a233a, the FBI would likewise need to tread carefully in its interactions with social-media companies, potentially eschewing communications that protect national security, public safety, or the security of federal elections. For example, particularly in the early stages of an investigation, law-enforcement officials may be uncertain whether a social-media post involves unprotected criminal activity (such as a true threat). But the injunction leaves them guessing what quantum of certainty they must possess before they can inform social-media companies about the post, potentially leading to disastrous delays.

To be sure, Judge Doughty’s injunction included a bunch of carve outs that, right wingers like Alito claim, ensures their efforts to force Twitter to publish Hunter Biden’s dick pics don’t make the country less safe. The carve outs are:

(1) informing social-media companies of postings involving criminal activity or criminal conspiracies;

(2) contacting and/or notifying social-media companies of national security threats, extortion, or other threats posted on its platform;

(3) contacting and/or notifying social-media companies about criminal efforts to suppress voting, to provide illegal campaign contributions, of cyber-attacks against election infrastructure, or foreign attempts to influence elections;

(4) informing social-media companies of threats that threaten the public safety or security of the United States;

(5) exercising permissible public government speech promoting government policies or views on matters of public concern;

(6) informing social-media companies of postings intending to mislead voters about voting requirements and procedures;

(7) informing or communicating with social-media companies in an effort to detect, prevent, or mitigate malicious cyber activity;

(8) communicating with social-media companies about deleting, removing, suppressing, or reducing posts on social-media platforms that are not protected free speech by the Free Speech Clause in the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. [my emphasis]

The carve outs — to the extent that they apply to the FBI, as most by definition do — actually demonstrate the problem with this ruling (and may explain the stakes of the focus on the “Hunter Biden” “laptop”).

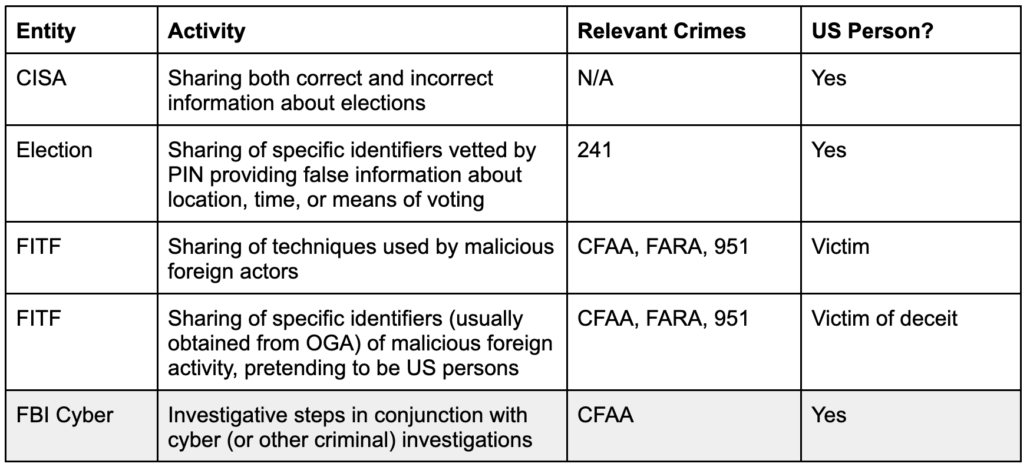

Five kinds of interaction with social media

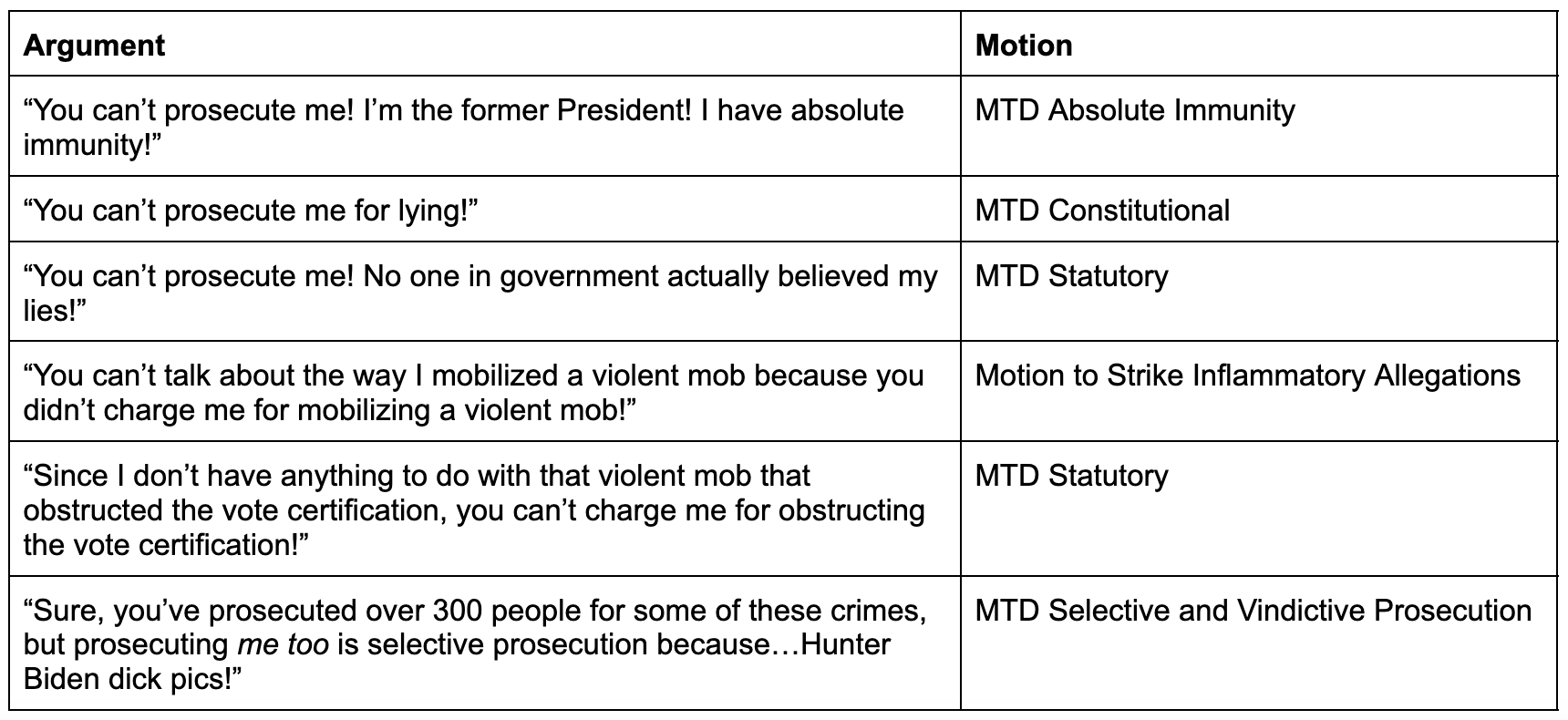

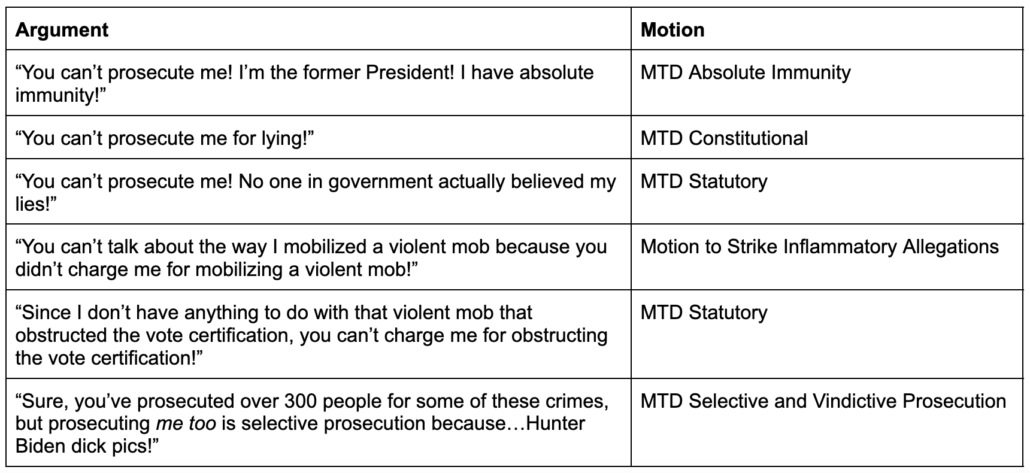

To see why, it’s useful to understand what the plaintiffs actually complained about (which largely tracks Matt Taibbi’s misrepresentations in his Twitter Files propaganda), which are shown in the unshaded rows in the table below.

CISA

First, there’s the Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency. It was set up within DHS specifically to provide an alternative to the FBI, a non-law enforcement agency that could help protect critical infrastructure, including elections, from cyber as well as brick-and-mortar threats. In addition to its efforts to combat disinformation about elections, for example, CISA has also helped some states harden their election systems against hacking attempts, run active shooter drills with election officials, and helped state election officials recover after natural disasters.

As part of its election role, though, CISA aspired to provide authoritative information to election partners (including social media companies) about both intentional and unintentional incorrect information about elections. The example former CISA Director Chris Krebs provided to the January 6 Committee was an Iranian campaign, active in the days after the Hunter Biden story, to pose as members of the Proud Boys and intimidate people of color not to vote. But in the same way that CISA would help protect pipelines against international or domestic attackers, CISA would track and provide official debunking to incorrect information from both international and domestic sources. Republicans especially hate CISA because Krebs affirmed that the 2020 election had been conducted securely (after which Trump summarily fired him by Tweet). But they also object to the “switchboarding” role that CISA has served, getting reports on incorrect information (which of course could include domestic actors) from election officials, along with corrections, and sharing them with social media companies.

At first, the Fifth Circuit reversed Doughty’s injunction on CISA, but then arbitrarily added them back in, a flaky move that may have contributed to SCOTUS’ decision to review the Fifth Circuit’s actions.

Election Command Post

Then there’s the intervention that might be the most controversial, but which in this litigation got replaced by the right wing obsession with the “Hunter Biden” “laptop.” In the days immediately preceding the 2020 election, FBI agents passed on social media identifiers that misstated the time, place, or means of voting. Per the testimony of Agent Chan, these had been vetted by Public Integrity lawyers at Bill Barr’s DOJ and deemed to be “criminal in nature.” This is the primary instance where the FBI shared information about US persons that might be taken down. It’s also a use case that Matt Taibbi wildly misrepresented, both as to the genesis of the data and the potential existence of ongoing criminal investigations into the activity. And it’s one instance where, under Doughty’s carve out #6, you could see the FBI hesitating before sharing: because while the identifiers in question did mislead about “voting requirements and procedures,” the FBI would’t be able to establish intent without more work (including more intrusive legal process on the accounts). So there’d be no way for the FBI to flag these accounts until it had done more work to determine intent, after which the damage would have been done. This should be where discussions at SCOTUS focus. But they’re not. Instead, Alito is talking about the “Hunter Biden” “laptop.”

FITF: Strategic and Tactical

Finally, there is the FBI’s Foreign Influence Task Force, now led by Laura Dehmlow (the other FBI official specifically enjoined; in 2020 she was the Unit Chief of the Chinese group at FITF). FITF aims to combat malign foreign influence operations, defined as efforts by foreign actors, hiding their foreign identity, to target those inside the US. While such efforts can target elections, they can also be part of traditional espionage and hacking efforts or attempts by authoritarian governments to crack down on US-based dissidents.

FITF interacts (or did, before the injunction) with social media companies in two ways. They hold general meetings — often attended by Chan and Dehmlow — to discuss general tips and techniques about foreign actors, what they called “strategic” information sharing. And they hold one-on-one meetings with social media platforms to discuss specific activity on their platforms — what the FBI calls “tactical.” The leading source of such tactical information, per Dehmlow’s testimony to the House Judiciary Committee, is “another government agency,” often classified information downgraded to share with partners, though Chan described that FBI agents involved in specific counterintelligence or criminal investigations might also share information.

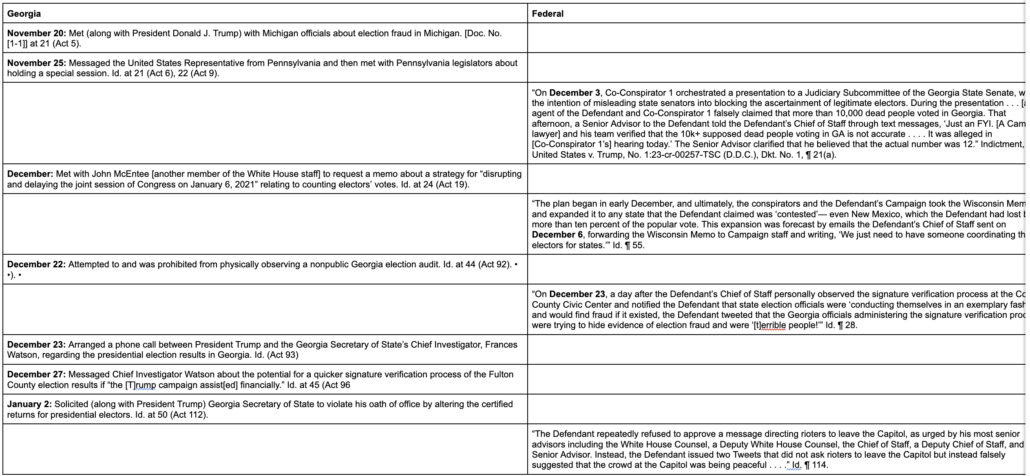

We know that the plaintiffs in this lawsuit misrepresented this sharing. In addition to general descriptions of this information sharing from depositions, we have rather specific evidence about the subject of these FITF briefings in 2020. LinkedIn emails that Doughty claims to rely on, for example, show that the August 2020 agenda for the FITF meeting covered the Internet Research Agency — the Internet trolls that Republicans like to claim were the only way Russia has interfered in elections — but also described a Russian software and influence campaign targeting Ukraine. It shows a specific briefing on APT31, which Mandiant describes as, “a China-nexus cyber espionage actor focused on obtaining information that can provide the Chinese government and state-owned enterprises with political, economic, and military advantages.” That briefing also covered Iran, Venezuela, and North Korea.

While the September 2020 briefing reviewed a fake right wing news site run by IRA (the FBI had just targeted a similar left wing fake news site as well), it discussed three things pertaining to Iran: some influence campaign (as noted, in October CISA would share details of a very sophisticated campaign in 2020 hijacking Proud Boy identities to discourage voters of color), a recent indictment of hackers with ties to IRGC who had targeted (among other things) an American satellite company, and a toolset of some Iranian hackers.

The agenda for the October meeting was not as detailed as the August and. September ones, but a follow-up shows that one item pertained to a Global (meaning something other than Chinese or Russian) campaign targeting Trump, Republicans, and Biden.

This is the kind of information sharing that Judge Doughty’s injunction threatens to end: efforts (among other things) to prevent Iranian and Chinese hacking of US technology companies.

While the subjects of FITF briefing might include Americans — such as the freelancers paid by the IRA’s fake news site or the Trump associates, like Roger Stone and Hannity, who engaged with fake IRA Twitter accounts — they are targeted at selectors that the FBI has “high confidence” are foreigners pretending to be American.

Criminal Process

Thanks to Matt Taibbi’s propaganda, right wingers have completely ignored the role of criminal process in all this, even though Agent Chan repeatedly described in his deposition that, “The majority of my role is dealing with cyber investigations.” There is clear overlap between the things right wingers complain about and known criminal investigations. As I have noted, for example, right in the middle of the 2020 pre-election period, DOJ rolled out a GRU indictment which included the 2017 hack-and-leak operation targeting Emmanuel Macron, in which key members of the far right, including Jack Posobiec, were involved.

Chan described several times that his team not only investigated part of the 2016 hack, but still had an active investigation into those actors. That’s important not only because he would have firsthand knowledge of the kinds of attribution social media companies (and Google and Microsoft) had in 2016, but for another reason: On October 19, 2020, DOJ indicted a bunch of GRU hackers, including one charged in the 2016 hack-and-leak campaign, for a variety of additional hacks, including the hack-and-leak targeting Emmanuel Macron. The Macron campaign, specifically, included both Google and Twitter components. So in the very same weeks when — right wingers complain — Elvis Chan was in close contact with Twitter about the ongoing election, he or his subordinates were likely working with prosecutors in Pittsburgh on an indictment implicating both Google and Twitter.

Emmanuel Macron is not mentioned in the Chan deposition.

The investigation into Douglass Mackey, for intentional disinformation targeting Blacks and Latinos regarding the means of voting, would have been active in this period as well. Those disinformation efforts were substantially orchestrated in Twitter DM threads.

While Agent Chan likely had no involvement in the Mackey case, he has investigated GRU for years, so likely would have been aware of the investigative steps leading up to the 2020 indictment. The press release for that indictment specifically commended the cooperation of Google, Facebook, and Twitter in the investigation.

In other words, not only did FBI provide notice of disinformation from US persons pertaining to content vetted by DOJ attorneys as potential crimes, but some of the contacts FBI had with Twitter in the period would involve far right wing involvement with actual crimes.

Rudy Giuliani and Steve Bannon and FITF

The right wing has focused on FITF rather than other aspects of their complaint because, at an FITF briefing with Twitter shortly after the NYPost story on the “Hunter Biden” “laptop,” someone at Twitter asked about it and an FBI person present said, “the laptop is real,” and then, in a briefing with Facebook, someone asked about it and Dehmlow responded “no comment.” Based on that exchange (and three erroneous details), Judge Doughty finds great fault with the FBI.

The FBI’s failure to alert social-media companies that the Hunter Biden laptop story was real, and not mere Russian disinformation, is particularly troubling. The FBI had the laptop in their possession since December 2019 and had warned social-media companies to look out for a “hack and dump” operation by the Russians prior to the 2020 election. Even after Facebook specifically asked whether the Hunter Biden laptop story was Russian disinformation, Dehmlow of the FBI refused to comment, resulting in the social-media companies’suppression of the story. As a result, millions of U.S. citizens did not hear the story prior to the November 3, 2020 election. Additionally, the FBI was included in Industry meetings and bilateral meetings, received and forwarded alleged misinformation to social-media companies, and actually mislead [sic] social-media companies in regard to the Hunter Biden laptop story. The Court finds this evidence demonstrative of significant encouragement by the FBI Defendants.

On top of the three errors Doughty makes (which I’ll get to), there are several problems here. First, confirming that the FBI knew the laptop was real, as the FBI did, was a privacy violation! Hunter Biden is the one who has complaint for the disclosure of an ongoing criminal investigation (which is, according to Agent Chan, why Dehmlow responded no comment to the Facebook question), not the right wing.

More importantly, based on what is publicly known, Hunter Biden would normally not be included FITF briefing. He’s a US citizen. While several of his international relationships (with Burisma, with Romania, and with CEFC) were being investigated as potential FARA violations in 2020 and after, with the important exception of a slight delay in Burisma’s announcement of his appointment in 2014, Hunter’s ties to such entities were not covert. Nor is there any allegation he disseminated false information about those entities online, especially on Facebook and Twitter. CEFC might have been the subject of FITF focus, but more for its covert role in recruiting James Woolsey.

One person who might be included in FITF briefings in summer 2020, though, is Guo Wengui. Unlike Hunter Biden, he’s not a US citizen; he is (or was, before his indictment in March) present in the US as an asylum seeker. And as public reports from July 2020 described, the source of funding for his propaganda efforts was under FBI investigation, precisely the kind of covert relationship of interest to FITF. That reporting suggested that Guo might secretly be funded by the Chinese state to track Chinese dissidents, something Dehmlow has explicitly included within FITF’s mandate. In a filing in the current investigation against Guo, SDNY has pointed to evidence obtained in a more recent search of Guo’s property pertaining to a 2018 meeting between the UAE and China. In other words, in 2020, the FBI was actively investigating whether China and/or the Emirates funded propaganda put out by Guo, with Steve Bannon’s involvement, precisely the kind of secret foreign backing of influence campaigns that FITF focuses on. So while Hunter Biden shouldn’t have come up as a subject of FITF briefing, Bannon’s partnership with Guo might have.

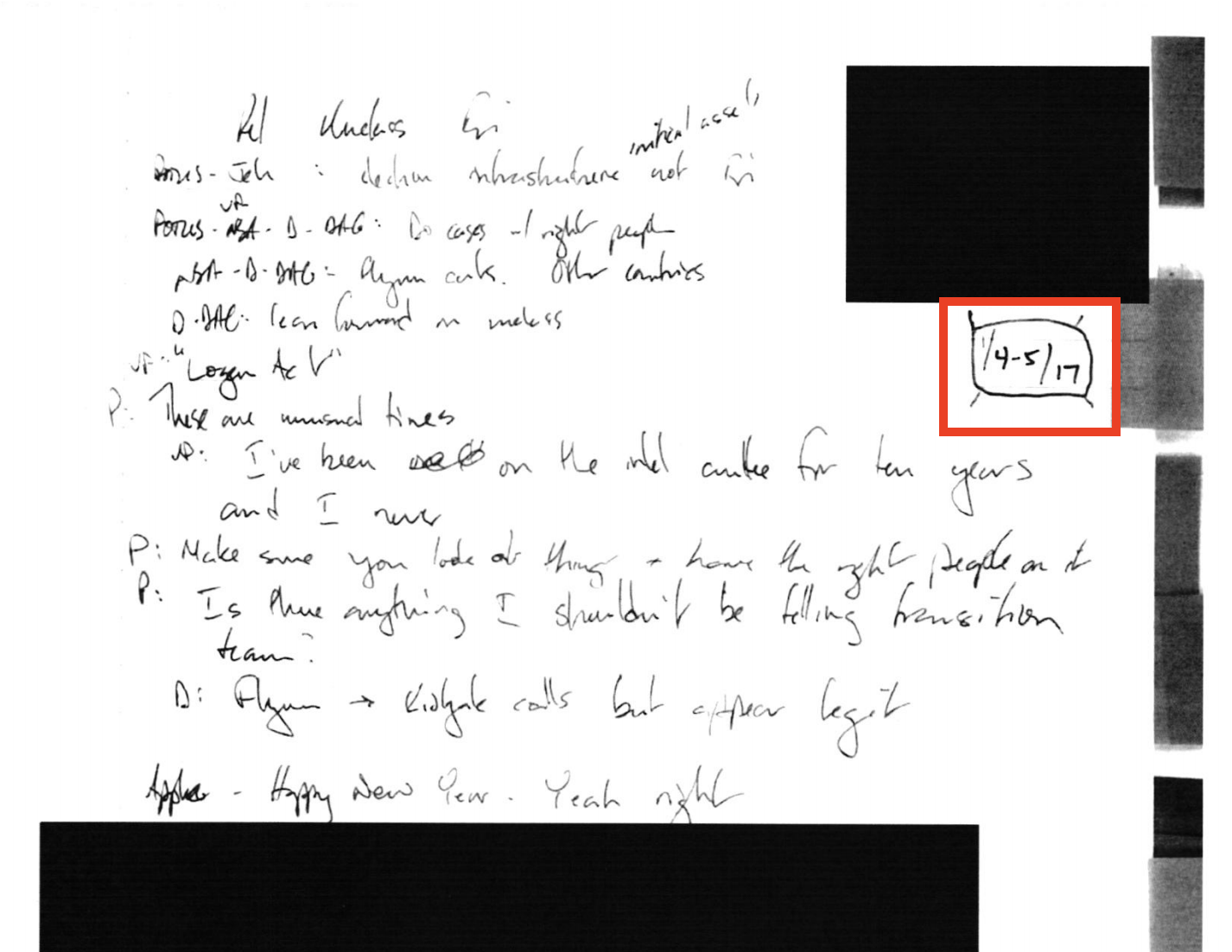

We don’t know whether that happened. But one person whose propaganda campaign definitely was a subject of FITF briefing is Andrii Derkach. Between the August and September face-to-face meetings, on September 10, 2020, a Unit Chief (presumably the Russian Unit Chief) at FITF sent a link to LinkedIn noting Treasury’s sanctioning of Derkach, explaining, “just want to let you know about someone we have discussed in previous briefings.” Obviously, the link was public, as was a WaPo story that same day tying Derkach to Rudy’s efforts to push criminal investigations related to Joe Biden. But the FBI sent the link, referencing back to prior discussions, to flag it for LinkedIn.

In other words, the far right is complaining that the FBI didn’t offer up details about an ongoing criminal investigation into Hunter Biden, but they’ve never complained that the FBI didn’t offer up details about a national security investigation into Steve Bannon’s propaganda partner (one who, subsequent reporting has confirmed, played a key role in altering and disseminating Hunter Biden dick pics). Nor have they complained that FBI didn’t offer up details about the counterintelligence investigation into the alleged Russian agent conducting an influence operation targeting Rudy at this meeting. Rudy and Bannon were named in the NYPost story in question, yet the right wing isn’t wailing that the FBI didn’t describe ongoing FBI investigations, investigations directly relevant to the mission of FITF, in the briefing after its release.

Doughty’s Three Errors

Which brings us, finally, to three errors that Doughty makes — at least one of which is already before SCOTUS — in sustaining his complaint that the FBI must be enjoined because they didn’t offer up more information about a criminal investigation into Hunter Biden.

First, in his opinion written in July, Doughty points to Yoel Roth’s 2020 FEC testimony, which is where Roth first explained that Twitter took down the initial NYPost link under its hack-and-leak policy.

(10) Yoel Roth (“Roth”), the then-Head of Site Integrity at Twitter, provided a formal declaration on December 17, 2020, to the Federal Election Commission containing a contemporaneous account of the “hack-leak-operations” at the meetings between the FBI, other natural-security agencies, and social-media platforms.405 Roth’s declaration stated:

Since 2018, I have had regular meetings with the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, the Department of Homeland Security, the FBI, and industry peers regarding election security. During these weekly meetings, the federal law enforcement agencies communicated that they expected “hack-and-leak” operations by state actors might occur during the period shortly before the 2020 presidential election, likely in October. I was told in these meetings that the intelligence community expected that individuals associated with political campaigns would be subject to hacking attacks and that material obtained through those hacking attacks would likely be disseminated over social-media platforms, including Twitter. These expectations of hack-and-leak operations were discussed through 2020. I also learned in these meetings that there were rumors that a hack-and-leak operation would involve Hunter Biden. 406 [emphasis original]

In his testimony, Agent Chan disputed the notion that that the FBI suggested a hack-and-leak would involve Hunter Biden, because Joe Biden’s son had not come up in meetings before the NYPost story he attended.

[I]n my estimation, we never discussed Hunter Biden specifically with Twitter. And so the way I read that is that there are hack-and-leak operations, and then at the time — at the time I believe he flagged one of the potential current events that were happening ahead of the elections.

That’s consistent with what Roth has said since, in House Oversight Testimony, clarifying that he heard the rumors about a hack-and-leak involving Hunter Biden from other social media companies, not the FBI.

I think it actually should have been two separate sentences. It is true that in meetings between industry and law enforcement, law enforcement discussed the possibility of a hack and leak campaign in the lead up to the election. And in one of those meetings, it was discussed, I believe, by another company that there was a possibility that that hack and leak could relate to Hunter Biden and Burisma. I don’t believe that perspective was shared by law enforcement. They didn’t endorse it. They didn’t provide that information in that.

But Doughty nevertheless relies on the outdated misinterpretation to blame the FBI for Twitter’s conclusions.

As noted, there’s no mention of one reason why this conclusion would be sound — the public reporting on Andrii Derkach, which was part of FITF briefing. Nor is there mention of the GRU hack of Burisma reported by a Silicon Valley InfoSec company earlier that year.

This lawsuit has thrived even after Agent Chan debunked one conspiracy theory about the social media’s throttling of the NYPost story, the false assumption that the FBI affirmatively told Twitter and Facebook that a hack-and-leak would involve Hunter Biden.

It has done so, in part, because of a truly bizarre — and erroneous — complaint from Doughty: That Chan and others at the FBI and CISA warned social media companies of hack-and-leak campaigns, like the GRU one of Macron indicted just days after the NYPost Hunter Biden story October 2020. Social media companies took the “Hunter Biden” “laptop” story down, the logic goes, because the FBI coerced them to change their moderation policies to prohibit publication of hacked materials.

In Doughty’s version, the social media companies responded to this pressure in 2020, just in time to use it to justify taking down the NYPost story.

Social-media platforms updated their policies in 2020 to provide that posting “hacked materials” would violate their policies. According to Chan, the impetus for these changes was the repeated concern about a 2016-style “hack-and-leak” operation.402 Although Chan denies that the FBI urged the social-media platforms to change their policies on hacked material, Chan did admit that the FBI repeatedly asked the social-media companies whether they had changed their policies with regard to hacked materials403 because the FBI wanted to know what the companies would do if they received such materials.404 [my emphasis]

In the Fifth Circuit’s telling, that change seems to date to 2022, two years after the “Hunter Biden” “laptop” story.

For example, right before the 2022 congressional election, the FBI tipped the platforms off to “hack and dump” operations from “statesponsored actors” that would spread misinformation through their sites. In another instance, they alerted the platforms to the activities and locations of “Russian troll farms.” The FBI apparently acquired this information from ongoing investigations.

Per their operations, the FBI monitored the platforms’ moderation policies, and asked for detailed assessments during their regular meetings. The platforms apparently changed their moderation policies in response to the FBI’s debriefs. For example, some platforms changed their “terms of service” to be able to tackle content that was tied to hacking operations. [my emphasis]

In fact, the Fifth Circuit builds most of its claim of FBI coercion on this change in terms of service (again, seemingly in 2022), which it ties to content take downs, the sole potential hack-and-leak example of which is that first article on the “Hunter Biden” “laptop.”

Fourth, the platforms clearly perceived the FBI’s messages as threats. For example, right before the 2022 congressional election, the FBI warned the platforms of “hack and dump” operations from “state-sponsored actors” that would spread misinformation through their sites. In doing so, the FBI officials leaned into their inherent authority. So, the platforms reacted as expected—by taking down content, including posts and accounts that originated from the United States, in direct compliance with the request. Considering the above, we conclude that the FBI coerced the platforms into moderating content. But, the FBI’s endeavors did not stop there.

We also find that the FBI likely significantly encouraged the platforms to moderate content by entangling itself in the platforms’ decision-making processes. Blum, 457 U.S. at 1008. For example, several platforms “adjusted” their moderation policies to capture “hack-and-leak” content after the FBI asked them to do so (and followed up on that request). Consequently, when the platforms subsequently moderated content that violated their newly modified terms of service (e.g., the results of hack-and-leaks), they did not do so via independent standards.

It’s a crazy enough argument on its face (especially the Fifth Circuit’s suggestion that a change in 2022 led to the throttling of a 2020 story). But it also gets the timing — and therefore the cause-and-effect — wrong. The actual change to Twitter’s policy, for example, was in March 2019, based off discussions before that. Either FBI planned their malicious coercion long before they got the laptop from JPMI, or the claim is utterly nonsensical.

DOJ called out this error in its SCOTUS response.

Similarly, respondents’ claim that the platforms “updated their policies in 2020” with respect to “‘hacked materials,’” such as “‘the laptop story,’” “after the FBI’s ‘impetus,’” Opp. 17, 19 (brackets and citations omitted), cannot be squared with the platforms’ own testimony that their actions with respect to the “laptop story” were based on policies adopted in 2018, C.A. ROA 18,498-18,499, 18,505.

In other words, the main claim that the Fifth Circuit made about coercion — which, again, was ultimately a claim about coercing social media companies to do something that prevented one story from going viral — got the timing and therefore any possible causality wrong.

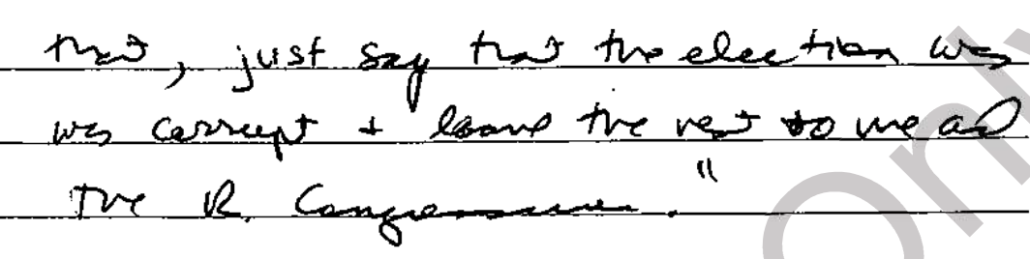

Finally, there’s the source of Doughty’s claim of animus on the part of the FBI, his claim that they deliberately withheld information that (he imagines) would have led Facebook and Twitter to act differently.

The mention of “hack-and-leak” operations involving Hunter Biden is significant because the FBI previously received Hunter Biden’s laptop on December 9, 2019, and knew that the later-released story about Hunter Biden’s laptop was not Russian disinformation. 408

Doughty bases this claim on a November 2, 2022 Miranda Devine (!!!) column. The column is, predictably, riddled with debunked propaganda, including the shoddy Intercept piece that kicked off this campaign, the lawsuit itself (making it a self-licking ice cream cone), and a preview of John Paul Mac Isaac’s then unpublished book (though not the line where an FBI agent told JPMI’s father, “You may be in possession of something you don’t own”).

The paragraph from which Doughty bases his claim that FBI “knew that the later-released story about Hunter Biden’s laptop was not Russian disinformation” appears to be this one:

We know the FBI at the time was spying on Rudy Giuliani’s online cloud with a covert surveillance warrant. Therefore, it had access to his emails in August 2020 from computer store whistleblower John Paul Mac Isaac and to my text messages discussing when The Post would publish the story. It sure looks as if the FBI deliberately pre-censored a legitimate story for a political aim.

Of course, the paragraph doesn’t mention Russian disinformation, nor does JPMI’s role in the process rule out Russian disinformation (a point I laid out here).

Plus, the paragraph is factually wrong. Per failed redactions in a Lev Parnas filing and other filings in that Special Master docket, FBI obtained a warrant Rudy’s iCloud account and emails on November 4, 2019, before John Paul Mac Isaac was subpoenaed by the FBI, and nine months before JPMI reached out to Rudy. Rudy’s phones were seized with an April 21, 2021 warrant, long after the controversy in question (though at least several of those phones were corrupted). While it’s certainly likely that DOJ obtained a second warrant for Rudy’s emails after that, it would not have happened in 2020. In other words, there is no known legal process that obtained Rudy’s emails that would have included JPMI’s emails to him before the NYPost story came out.

Plus, JPMI’s emails to Rudy would only be in the scope of the known warrant against Rudy … if the laptop were part of a Ukranian effort to deal dirt to cause legal problems for Joe Biden and his family.

Devine may base her claim, at least in part, elsewhere. Her column also alludes to the disgruntled FBI agents who attacked Tim Thibault.

This year, whistleblowers have come forward to finger various FBI employees engaged in the cover-up. Timothy Thibault, the recently retired assistant special agent in charge of the FBI’s Washington, DC, field office, was the agency point man to manage Tony Bobulinski, Hunter’s business partner who went to the FBI with evidence of the Biden influence-peddling operation. Thibault allegedly ordered the investigation closed and has refused to cooperate with GOP members of the House Judiciary Committee.

This, too, is false. Thibault’s House Judiciary Committee interview reveals that his only involvement with the Tony Bobulinski interview was to address Bobulinski’s request to turn over just some of the material on some of his devices.

But Devine’s reliance on such disgruntled agents is interesting for another reason: because they are likely disgruntled at least partly because of warnings against the involvement of Steve Bannon associate Peter Schweizer in the Hunter Biden investigation. The disgruntled agents falsely claimed, elsewhere, that Thibault, on his own, shut down Schweizer as a source. Yet according to Thibault’s testimony, he did so only after two warnings. First, the lead FBI agent on the Hunter investigative team told Thibault that getting contents of the laptop from Schweizer, which they had already gotten, “could cause problems when you get to prosecution … and [] open doors for defense attorneys.” And shortly thereafter — so temporally in the same time period as the first NYPost story — FITF raised concerns about the Bannon associate. A week after the NYPost story, around October 21, FITF provided Thibault a classified briefing (from which they excluded the line FBI agents, in part because the daughter of one was posting related content on Daily Caller). That briefing described more context about FITF’s concerns.

In spite of all the obvious problems with Devine’s propaganda, it formed a key part of Doughty’s claim that FBI coercion, rather than an independent series of decisions about hosting potentially stolen content, resulted in the throttling of the first NYPost story.

And based on that shoddy case — based on the feverish conspiracy theories about the “Hunter Biden” “laptop” sustained by Eric Schmitt and Jeff Landry and Miranda Devine — Judge Doughty made it significantly riskier for Agent Chan and others to work with social media companies to do things like prevent Iranian hacks of US satellite companies.