Last week, Glenn Greenwald did a podcast defending Bill Barr’s efforts to overturn the prosecution of Mike Flynn (here’s a transcript; the italicized language below is my correction of that transcript). A whole slew of people wrote me in alarm over some of the claims he made in it. After some reflection, I decided to do a post showing how the public record that Glenn claims to have consulted in his podcast at least undermines some of his claims, and in places utterly refutes it.

Two points about this. First, after I made it clear I was working on this in conversations with Glenn, he wrote this post, once again claiming to know details of what I shared with the FBI and what their response to that was, which I assume was an attempt to bully me into withholding this post. Ironically, The Intercept is fundraising off that post, celebrating a post that gets key details wrong. That is their prerogative. Glenn will apparently continue to make these claims; while there are baseless claims in it, I will continue to focus on correcting his baseless claims about other issues more central to current affairs.

Before Glenn posted that post, I asked if people would support this one by donating to my local food bank. This post took a great deal of work, at a time I’ve got far more important things to do from a reporting and personal perspective. If you recognize that work and if you can afford it at this time of crisis, please consider a donation to Feeding America West Michigan. Thanks!

False claim: Mueller acknowledged that the crime was not particularly serious by recommending that Flynn be sentenced to not a single day in prison

As “proof” that no one should be worried about DOJ’s actions with regards to Flynn, Glenn claims that prosecutors said Flynn’s crime was not serious and he should do no prison time.

These flamboyant warnings about the critical importance of the Flynn prosecution and the cataclysmic consequences of the Justice Department’s decision to request its dismissal are particularly odd since General Flynn was accused of a single crime lying to the FBI pled guilty to it. And then the prosecutor Robert Mueller and his prosecutorial team acknowledged that the crime was not particularly serious by recommending to the judge that General Flynn be sentenced to not a single day in prison, citing both the cooperation he gave to the prosecution as well as the nature of the crime. So even the prosecutors in this case, have said that the conviction that came from the plea bargain doesn’t warrant a second in prison time.

While Mueller’s team appeared amenable to probation in their first sentencing memo, they did not actually recommend probation, leaving it up to Judge Sullivan’s discretion. Moreover, they introduced their recommendation for a low end of guideline sentence by stating Flynn’s crime was serious.

The defendant’s offense is serious. As described in the Statement of Offense, the defendant made multiple false statements, to multiple Department of Justice (“DOJ”) entities, on multiple occasions.

[snip]

For the foregoing reasons, as well as those contained in the government’s Addendum and Motion for Downward Departure, the government submits that a sentence at the low end of the advisory guideline range is appropriate and warranted.

After Flynn tried to get cute in his own sentencing memo, the government reiterated the seriousness of Flynn’s crime.

The seriousness of the defendant’s offense cannot be called into question, and the Court should reject his attempt to minimize it. While the circumstances of the interview do not present mitigating considerations, assuming the defendant continues to accept responsibility for his actions, his cooperation and military service continue to justify a sentence at the low end of the guideline range.

When Judge Sullivan asked prosecutors about benefits Flynn had obtained from cooperating at the sentencing hearing, Brandon Van Grack indicated that Flynn had been exposed to conspiracy and Foreign Agent charges, which could amount to a ten or fifteen year sentence (which is what Flynn says Covington counseled him before he pled guilty).

THE COURT: I think that’s fair. I think that’s fair. Your answer is he could have been charged in that [EDVA] indictment.

MR. VAN GRACK: Yes, Your Honor.

THE COURT: And that would have been — what’s the exposure in that indictment if someone is found guilty?

MR. VAN GRACK: Your Honor, I believe, if you’ll give me a moment, I believe it was a conspiracy, 18 U.S.C. 371, which I believe is a five-year offense. It was a violation of 18 U.S.C. 951, which is either a five- or ten-year offense, and false statements — under those false statements, now that I think about it, Your Honor, pertain to Ekim Alptekin, and I don’t believe the defendant had exposure to the false statements of that individual.

THE COURT: Could the sentences have been run consecutive to one another?

MR. VAN GRACK: I believe so.

THE COURT: So the exposure would have been grave, then, would have been — it would have been — exposure to Mr. Flynn would have been significant had he been indicted?

MR. VAN GRACK: Yes. And, Your Honor, if I may just clarify. That’s similar to the exposure for pleading guilty to 18 U.S.C. 1001.

THE COURT: Right. Exactly. I’m not minimizing that at all. It’s a five-year felony.

MR. VAN GRACK: Yes, Your Honor.

THE COURT: Excuse me one second. (Brief pause in proceedings.)

THE COURT: Yes, Counsel.

MR. VAN GRACK: Your Honor, I’d clarify that the maximum penalty for 18 U.S.C. 951 is a ten-year felony and five years —

After Flynn blew up his plea deal, prosecutors got more explicit about the seriousness of Flynn’s crimes in their second sentencing memo, one that had to be delayed twice to get approvals from everyone in DOJ.

Given the serious nature of the defendant’s offense, his apparent failure to accept responsibility, his failure to complete his cooperation in – and his affirmative efforts to undermine – the prosecution of Bijan Rafiekian, and the need to promote respect for the law and adequately deter such criminal conduct, the government recommends that the court sentence the defendant within the applicable Guidelines range of 0 to 6 months of incarceration.

[snip]

The defendant’s false statements to the FBI were significant. When it interviewed the defendant, the FBI did not know the totality of what had occurred between the defendant and the Russians. Any effort to undermine the recently imposed sanctions, which were enacted to punish the Russian government for interfering in the 2016 election, could have been evidence of links or coordination between the Trump Campaign and Russia. Accordingly, determining the extent of the defendant’s actions, why the defendant took such actions, and at whose direction he took those actions, were critical to the FBI’s counterintelligence investigation.

[snip]

The defendant’s offense is serious, his characteristics and history present aggravating circumstances, and a sentence reflecting those factors is necessary to deter future criminal conduct. Similarly situated defendants have received terms of imprisonment.

[snip]

The defendant monetized his power and influence over our government, and lied to mask it. When the FBI and DOJ needed information that only the defendant could provide, because of that power and influence, he denied them that information. And so an official tasked with protecting our national security, instead compromised it.

The only time any sentencing memo raised probation was the reply memo in January, which came after Barr started the process of reversing Flynn’s prosecution.

As set forth below, the government maintains that a sentence within the Guidelines range – to include a sentence of probation – would be appropriate and warranted in this case.

[snip]

Based on all of the relevant facts and for the foregoing reasons, the government submits that a sentence within the Guidelines range of 0 to 6 months of incarceration is appropriate and warranted in this case, agrees with the defendant that a sentence of probation is a reasonable sentence and does not oppose the imposition of a sentence of probation.

Inapt comparison: Bill Barr’s orchestration of Cap Weinberger’s pardon is worse than Bill Barr doing the pardon here

In a crazy bit of straw man argument, Glenn claims (with no evidence) that those complaining about the Flynn matter don’t also care about past abuses of clemency and prosecutorial discretion.

And yet we’re hearing that the refusal to proceed with it is the end of American justice as we know. Apparently under this view, prior subversions of justice by the executive branch, such as the Act that I regard as the single most corrupt attack on basic justice in the United States, which is a decision by President Bush 41 to pardon numerous of his closest aides implicated in crimes relating to the Iran–Contra scandal, including his defense secretary, Caspar Weinberger who had been charged with perjury crimes and trials that would have likely led to the investigation and probably the conviction of President Bush 41 himself.

The comparison is inapt for reasons that go to the core of how we hold the President accountable for abuse of his Article II authority.

Mueller has made it clear that if Trump weren’t the President, he would have been indicted for obstruction. One act of his obstruction involved firing Jim Comey in an attempt to end the investigation into Flynn. Another involved calling Flynn’s lawyer, Rob Kelner, and demanding that Kelner alert him if he was implicating the President. Which is to say, even before Barr’s actions here, Trump had taken steps Poppy Bush is not known to have done to try to prevent Flynn from implicating him in — among other things — working to undercut sanctions imposed on Russia in the wake of the 2016 election.

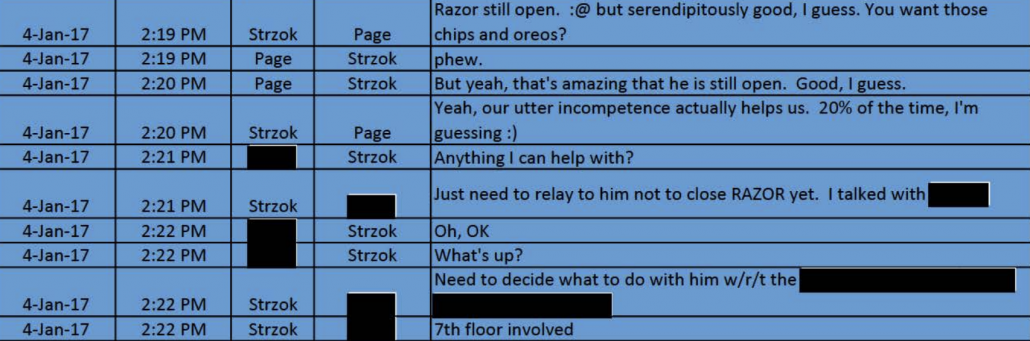

The evidence strongly suggests that Flynn avoided implicating Trump in the strategy of the Kislyak call, in a way that matched Trump’s public denials. Here’s how the Mueller Report concluded it did not have sufficient evidence to conclude that Flynn lied to the FBI to protect Trump.

Some evidence suggests that the President knew about the existence and content of Flynn’s calls when they occurred, but the evidence is inconclusive and could not be relied upon to establish the President’s knowledge.

[snip]

Our investigation accordingly did not produce evidence that established that the President knew about Flynn’s discussions of sanctions before the Department of Justice notified the White House of those discussions in late January 2017.

This is a matter about which Trump tried to create a contemporaneous record, one John Eisenberg thwarted to avoid obstruction exposure.

The next day, the President asked Priebus to have McFarland draft an internal email that would confirm that the President did not direct Flynn to call the Russian Ambassador about sanctions.253

It’s one of the topics the White House scripted Steve Bannon to give in his HPSCI testimony.

And it goes to a question Trump blew off entirely in his response to Mueller.

i. What consideration did you give to lifting sanctions and/or recognizing Russia’s annexation of Crimea if you were elected? Describe who you spoke with about this topic, when, the substance of the discussion(s).

That is, Flynn’s limited cooperation on the Russian investigation did not implicate Trump in ways that would have exposed him legally.

That’s the background to Bill Barr’s actions since January. The difference between this and the Weinberger pardon is precisely the point. If, when prosecutors explicitly called for prison time in January, Trump had simply pardoned Flynn, it would the equivalent of the Weinberger pardon. In addition, Trump would face the direct political consequences of doing so in November.

Instead, leading up to his motion to dismiss, Barr (the architect of the Weinberger pardon, but Glenn doesn’t mention that) removed a Senate-confirmed US Attorney, installed an unconfirmed flunky to oversee career prosecutors, and then got an outsider to go “find” documents that had already been reviewed by two outside oversight entities (DOJ IG and John Durham). Then Barr overrode the career prosecutors’ decision to move to dismiss the prosecution. He has subsequently replaced the past flunky at DC USAO with another one. That is, Barr is putting people in place solely to protect those who’ve refused to testify against Trump law, and doing it in a way that limits the political cost Poppy incurred with the Weinberger pardon. It also limits what Barr himself conceded might be further exposure for Trump for obstruction charges.

Misdirection: The FBI was corrupt during the 2016 election

Glenn complains that the entire Deep State (including the NSA, which is particularly crazy given that Mike Rogers was interviewing with Trump at a time he was at odds with his bosses) acted corruptly during the 2016, with the implication that this affected Trump.

There’s another reason it’s so important to understand what happened in this case, which is that it sheds light on and directly relates to very widespread corruption on the part of the FBI, the CIA, the NSA, the DOJ and other agencies within the US security state during the 2016 election. For overtly political ends we already know of several extremely shocking revelations demonstrating abuse of power on the part of those agencies as part of the 2016 election.

This feels like just word diarrhea, so maybe Glenn hasn’t thought through what he said. But Glenn seems to suggest any corruption at DOJ and CIA and FBI (and NSA?!?!) harmed Trump.

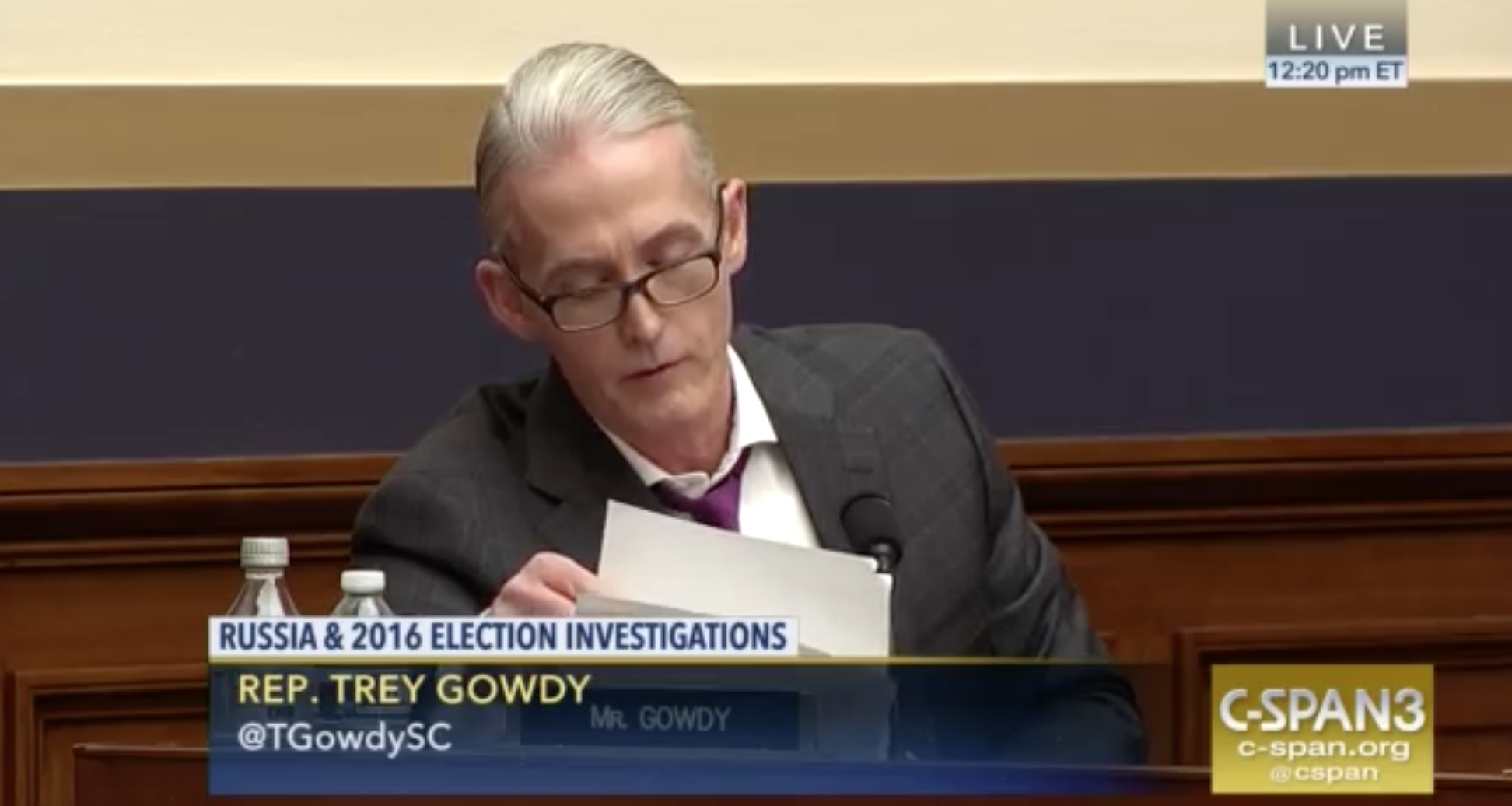

It’s true that the FBI opened an investigation into four people associated with Trump’s campaign based off a tip from Australia, one that John Durham has said should have been opened as a Preliminary Investigation rather than a Full one (which would have no affect on techniques used).

It’s true that the Carter Page FISA application — obtained close to the end of the election and in secret — had real problems, though DOJ IG did not conclude that those errors arose from political bias. With respect to Woods Procedure violations, Page’s applications were actually better than a bunch DOJ IG later reviewed. Moreover, the worst problems on the Page applications came later, on the last two applications, under the Trump Administration. While Trump’s DOJ withdrew the probable cause determination for the third and fourth Carter Page application, it has not done so for the two earlier ones.

Meanwhile, two people have been fired for their actions in 2016. Both did things that did major damage to Hillary Clinton. Jim Comey was fired in part because repeatedly violated DOJ’s prohibitions about discussing declinations (and in part because he didn’t coordinate the declination statement with DOJ). And Andrew McCabe was fired because he confirmed the existence of an investigation into the Clinton Foundation and allegedly lied about doing so to DOJ’s IG. (Whether he actually did lie remains the subject of litigation; DOJ failed to get an indictment against McCabe and DOJ IG withheld the testimony of Michael Kortan from his report on it).

The investigation into the Clinton Foundation, unlike the investigation into Trump’s campaign, had been predicated off of GOP oppo research, Clinton Cash, and it was leaked before McCabe confirmed it.

In fact, the only evidence the DOJ IG Report provided of biased agents handling informants targeting a candidate involved that same Clinton Foundation investigation.

We reviewed the text and instant messages sent and received by the Handling Agent, the co-case Handling Agent, and the SSA for this CHS, which reflect their support for Trump in the 2016 elections. On November 9, the day after the election, the SSA contacted another FBI employee via an instant messaging program to discuss some recent CHS reporting regarding the Clinton Foundation and offered that “if you hear talk of a special prosecutor .. .I will volunteer to work [on] the Clinton Foundation.” The SSA’s November 9, 2016 instant messages also stated that he “was so elated with the election” and compared the election coverage to “watching a Superbowl comeback.” The SSA explained this comment to the OIG by saying that he “fully expected Hillary Clinton to walk away with the election. But as the returns [came] in … it was just energizing to me to see …. [because] I didn’t want a criminal to be in the White House.”

On November 9, 2016, the Handling Agent and co-case Handling Agent for this CHS also discussed the results of the election in an instant message exchange that reads:

Handling Agent: “Trump!”

Co-Case Handling Agent: “Hahaha. Shit just got real.”

Handling Agent: “Yes it did.”

Co-Case Handling Agent: “I saw a lot of scared MFers on … [my way to work] this morning. Start looking for new jobs fellas. Haha.”

Handling Agent: “LOL”

Co-Case Handling Agent: “Come January I’m going to just get a big bowl of popcorn and sit back and watch.”

Handling Agent: “That’s hilarious!” [my emphasis]

Perhaps Glenn meant to incorporate FBI’s failures involving Hillary investigations in his comments, but if so, he didn’t mention it.

False claims: The Mueller Report represented the completion of all Trump-related investigations and Mueller gave no “hint” of any leverage over Trump

Glenn continues to misrepresent what the Mueller Report was.

The Mueller investigation itself revealed that the two critical conspiracy theories that drove “Russiagate” [sic] for three years number one that Donald Trump and the Trump campaign conspired with the Kremlin to interfere in the 2016 election and that number two the Kremlin exerted all kinds of blackmail leverage over Donald Trump to effectively be able to rule the United States for the benefit of Moscow using not just compromising videotapes, but also financial leverage. We know that all of that turned out to be a myth, a conspiracy theory without basis. And we know that for all kinds of reasons, particularly the fact that the Mueller investigation, after 18 months of highly aggressive subpoena driven probes into every component of those conspiracy theories ended without indicting even a single American, not one single American indicted for the crime of conspiring with Russia to interfere in the 2016 election in the Muller report didn’t even hint that let alone give credibility to let alone prove that there was any leverage being exerted over Donald Trump or the Trump White House by the Kremlin when it comes to things like blackmail average or other financial leverage.

Congratulations to Glenn for, this time, not exaggerating how long Mueller worked (22 months) like he normally does.

But Glenn continues to misunderstand both the allegations and the evidence.

First, in addition to any compromise (primarily financial, not the pee tape) tied to the crimes Mueller investigated, there was also the issue of a quid pro quo, Trump trading policy considerations in exchange for Russia’s election help.

In particular, the investigation examined whether these contacts involved or resulted in coordination or a conspiracy with the Trump Campaign and Russia, including with respect to Russia providing assistance to the Campaign in exchange for any sort of favorable treatment in the future. Based on the available information, the investigation did not establish such coordination.

That’s precisely why Flynn’s actions on sanctions were so important (as the language from the second sentencing memo makes clear). Glenn pretends that wasn’t investigated.

As regards to any “hint” of evidence of a conspiracy, the report specifically says that, “A statement that the investigation did not establish particular facts does not mean there was no evidence of those facts.” And when Glenn says the Report did not hint at such a relation, he necessarily is ignoring:

- The improbably lucrative real estate deal offered to Trump with the involvement of a former GRU officer

- The meeting offering dirt where Don Jr said the campaign would revisit a request for sanctions relief if they won

- Paul Manafort’s sharing of internal campaign information with a GRU-connected oligarch, including at a meeting where he also discussed carving up Ukraine to Russia’s liking; Manafort continued to pursue the Ukraine effort until he was jailed

- Roger Stone’s efforts to optimize the WikiLeaks releases which — recent releases make clear — the FBI believes or believed involved advance notice of the dcleaks and Guccifer personas, followed by Stone’s effort to pay off Assange with a pardon, starting seven days after the election

Glenn also misconstrues the scope of the investigation, which included the transition period but (probably for very important constitutional reasons), with respect to a quid pro quo or even Putin’s influence over Trump (but not obstruction), ended on Inauguration Day. Similarly, he misconstrues the scope of the Report, which explicitly said it did not include counterintelligence issues like blackmail (something I’ve tried to help Glenn correct his errors on before).

Most importantly, Glenn again claims, in spite of abundant public records to the contrary, that Mueller reported after finishing everything up. That ignores the twelve sealed referrals, of which just the George Nader prosecution has been disclosed (though one surely relates to Jerome Corsi and another probably pertains to Stone).

It ignores documented evidence of ongoing investigations (another thing I already laid out for Glenn’s benefit):

It is a fact, for example, that DOJ refused to release the details of Paul Manafort’s lies — covering the kickback system via which he got paid, his efforts to implement the Ukraine plan pitched in his August 2, 2016 meeting, and efforts by another Trump flunkie to save the election in the weeks before he resigned — because those investigations remained ongoing in March [2019]. There’s abundant reason to think that the investigation into Lev Parnas and Igor Fruman and Rudy Giuliani, whether it was a referral from Mueller or not, is the continuation of the investigation into Manafort’s efforts to help Russia carve up Ukraine to its liking (indeed, the NYT has a piece on how Manafort played in Petro Poroshenko’s efforts to cultivate Trump today).

It is a fact that the investigation that we know of as the Mystery Appellant started in the DC US Attorney’s office and got moved back there (and as such might not even be counted as a referral). What we know of the challenge suggests a foreign country (not Russia) was using one of its corporations to pay off bribes of someone. [Note: I have reason to believe, given a redaction in the recently-released Rosenstein scope memo, that this investigation is ongoing.]

It is a fact that Robert Mueller testified under oath that the counterintelligence investigation into Mike Flynn was ongoing.

KRISHNAMOORTHI: Since it was outside the purview of your investigation your report did not address how Flynn’s false statements could pose a national security risk because the Russians knew the falsity of those statements, right?

MUELLER: I cannot get in to that, mainly because there are many elements of the FBI that are looking at different aspects of that issue.

KRISHNAMOORTHI: Currently?

MUELLER: Currently.

That’s consistent with redaction decisions made both in the Mueller Report itself and as recently as last week.

And it ignores documents released in the last month that show that, in September 2018, the government took a number of steps in a Foreign Agent investigation that were deliberately hidden from Stone (and all the rest of us). The redactions in those filings indicate the investigation remains ongoing. In addition to Foreign Agent charges, it includes conspiracy among the crimes being investigated. The prosecution of Stone on False Statements charges was, in part, an effort to obtain Stone’s notes of his election-year meetings with Trump and his encrypted communications in support of this more serious investigation.

Based on very recent documents, DOJ continues to investigate Trump’s rat-fucker for conspiracy and Foreign Agent charges. The Mueller Report clearly does not reflect the end result of these investigations, including with regards to whether Mueller believed any of Trump’s aides had conspired with Russia or its surrogates.

False claim: FBI had no basis for believing Carter Page was an Agent of Russia

Glenn claims that the FBI had no reason to believe Carter Page was an Agent of Russia.

Perhaps the most egregious of it concerns the spying that was done by the FBI by the Justice Department on US citizen and former Trump advisor Trump campaign advisor Carter page. It was revealed throughout 2017 and into 2018 that the FBI had obtained FISA warrants to spy on the communications of Carter Page. spying on the email and telephone communications of a US citizen is one of the most draconian acts that the FBI and the US government can do. And yet they did it to Carter Page after shortly after he had served as an advisor to the Trump campaign yet while the presidential campaign was still underway, and for two years we heard Carter Page is clearly an agent of the Russian government. He was clearly a key cog in the conspiracy to conspire between Trump the Trump campaign and Russia to interfere in the election. We heard it vehemently denied that the Steele dossier, the unproven unvetted mountain of allegations served as a basis for the FISA allegation and yet, after a very comprehensive investigation, by the Inspector General of the Department of Justice in 2019, a comprehensive report was issued that concluded that not only was there no basis for believing that Carter Page was an agent of the Russian government, but the FBI lied to the FISA court, in order to obtain the warrants, to eavesdrop on him an incredibly serious scandal for the FBI to spy on somebody who had been associated with a rival campaign during a presidential election, when it turned out that not only was there no basis for doing so, but that they actually lied to the court in order to obtain those warrants, and it was the Mueller Report itself. That made clear that there was never any reason to believe, contrary to the definitive assertions of the media and political consensus that we heard for years, there was no reason to believe that Carter Page was ever an agent of the Russian government.

The actions of the FBI on the Carter Page FISA applications are inexcusable (note, Glenn gets the dates of the FISAs wrong, but that’s not important). It’s clear that Kevin Clinesmith, in June 2017, affirmatively misrepresented information key to the application. And after the FBI started learning of problems with the Steele dossier, largely in 2017, they did not incorporate that into their applications about Page. Nothing excuses that.

The FBI opened a counterespionage investigation into Carter Page on April 6, 2016, long before that application, based off actions that preceded his designation as a Trump advisor.

The IG Report explained why there was basis to investigate Page as a foreign agent: because he not only willingly shared non-public economic information with known Russian intelligence officers, extending beyond the time he was closed by the CIA as an approved contact (and CIA did not know all instances in which he had done so), but when his role in the Evgeny Buryakov prosecution became clear, Page seemed to affirmatively seek to resume contact with the Russians. In addition, it (and released 302s) made it clear that Page tried to deny doing so when asked by the FBI about this in a follow-up. The DOJ IG Report also laid out how Page believed he would cash in on his ties with Russia. And the 302s show that the FBI did get information from witnesses that seemed to corroborate some of the claims in the Steele dossier (or at least indicate that Steele was getting the same rumors that some of the people who set up Page’s trips to Russia got). The Mueller Report also shows that Page was representing himself as Trump advisor on Ukraine policy during his December 2016 trip to Moscow, actions that (if they weren’t sanctioned by Trump, as they appear not to have been) damaged the President-elect. The IG investigators did not review all the intelligence obtained via the FISA order.

Also of note, DOJ IG did not understand the predication of the investigation against Page until after the report was published, misunderstanding that 18 USC 951 is a different crime than FARA, and as a result conducted a First Amendment analysis that would have been passed based off the economic espionage actions with known Russian intelligence officers.

The Mueller Report that Glenn treats as the end all and be all of the matter makes it clear the government still had questions about what happened with Page in Russia (and released 302s make it clear the government wasn’t able to account for all of Page’s time in Moscow).

The Office was unable to obtain additional evidence or testimony about who Page may have met or communicated with in Moscow; thus, Page’s activities in Russia-as described in his emails with the Campaign-were not fully explained.

And a redacted passage in the declinations section of the report (page 183) clearly provides more context.

False claim: FBI planted Stefan Halper within the Trump campaign

After a long rant about what a terrible person Stefan Halper is (which is beyond my focus), Glenn claims that the FBI planted him “within” the Trump campaign.

And yet Halper pops up in the middle of the Russia gate investigation to serve as an informant on the part of the FBI essentially a spy planted within the circle of Trump campaign officials to approach George Papadopoulos and to approach Carter Page and report back what he was hearing and finding to the FBI. Exactly what has long been claimed that the FBI had essentially planted a spy, a former CIA operative with close ties to the Bush’s within the Trump campaign during the course of the presidential election.

The DOJ IG Report describes that when the FBI first reached out to Stefan Halper to serve as an informant in the investigation, they were focused exclusively on Papadopoulos. But then Halper revealed he had already met Carter Page in July, and Page had asked him to join the campaign; Halper was already expecting a call from someone senior (presumably Sam Clovis) about joining the campaign, but said he did not want to join the campaign.

Case Agent 1 told the OIG that the team asked Source 2 about Papadopoulos, but Source 2 said he had never heard of him. The EC documenting the meeting reflects that Source 2 agreed to work with the Crossfire Hurricane team by reaching out to Papadopoulos which would allow the Crossfire Hurricane team to collect assessment information on Papadopoulos and potentially conduct an operation.

Case Agent 1 told the OIG that Source 2 then asked whether the team had any interest in an individual named Carter Page. Case Agent 1 said that the members of the investigative team “didn’t react because at that point we didn’t know where we were going to go with it” but asked some questions about how Source 2 knew Carter Page. Source 2 explained that, in mid-July 2016, Carter Page attended a three-day conference, during which Page had approached Source 2 and asked Source 2 to be a foreign policy advisor for the Trump campaign. According to the EC summarizing the August 11, 2016 meeting, Source 2 said he/she had been “non-committal” about joining the campaign when discussing it with Carter Page in mid-July, but during the August 11, 2016 meeting with the Crossfire Hurricane team, Source 2 “stated that [he/she] had no intention of joining the campaign, but [Source 2] had not conveyed that to anyone related to the Trump campaign.” Source 2 further stated he/she “was willing to assist with the ongoing investigation and to not notify the Trump campaign about [Source 2’s] decision not to join.” Source 2 also told the Crossfire Hurricane team that Source 2 was expecting to be contacted in the near future by one of the senior leaders of the Trump campaign about joining the campaign.

Everyone on the team specifically said that if Halper did join the campaign they would not use him as an informant.

All of the FBI witnesses we interviewed said that they would not have used Source 2 for the Crossfire Hurricane investigation if Source 2 had actually wanted to join the Trump campaign. SSA 1 said he did not remember anyone on the Crossfire Hurricane team advocating for Source 2 to actually join the Trump campaign and told the OIG he was relieved that Source 2 did not want to join the campaign “at all.” Strzok told the OIG his reaction was “no, no, no, no, no, no…. [O]h god no. Absolutely not” when he learned that Source 2 had been invited to join the Trump campaign. Case Agent 1 told the OIG that if Source 2 had joined the campaign, the Crossfire Hurricane team would not have used Source 2 “because that’s not what we were after.”

It is true that Halper had taped interviews with Page (who had already reached out to Halper and who subsequently would invite Halper to join his Russian-funded think tank), Clovis, and Papadopoulos during the campaign. But the IG Report makes clear that these actions had the proper approvals and did not focus on campaign activities.

Unsubstantiated claim: Halper accused Svetlana Lokhova of being a honey pot entrapping Flynn

Meanwhile, Glenn suggests Halper accused Svetlana Lokhova honey trapped Flynn.

But also, it was the same Stephen Halper that first tried to raise concerns that General Flynn had should have his patriotism and his loyalties held under suspicion, because he claimed that General Flynn was speaking with and working with a Russian scholar, a woman named Svetlana Lokhova, who was at Oxford, and he was concerned Stephen Harper was he said that Svetlana Lokhova was basically a honeypot a sexpot, designed to entrap General Flynn to turn into a spy.

There are two aspects to this claim: that Halper’s allegations about Lokhova were part of the reason the FBI investigated Flynn and that Halper specifically accused Lokhova of being a honey pot.

The EC opening the investigation into Flynn shows that Lokhova was not included in the predication of the investigation against Flynn, which included his role on Trump’s campaign, his TS/SCI clearance, his acceptance of money from Russian state entities like RT, and his trip to Moscow in December 2015.

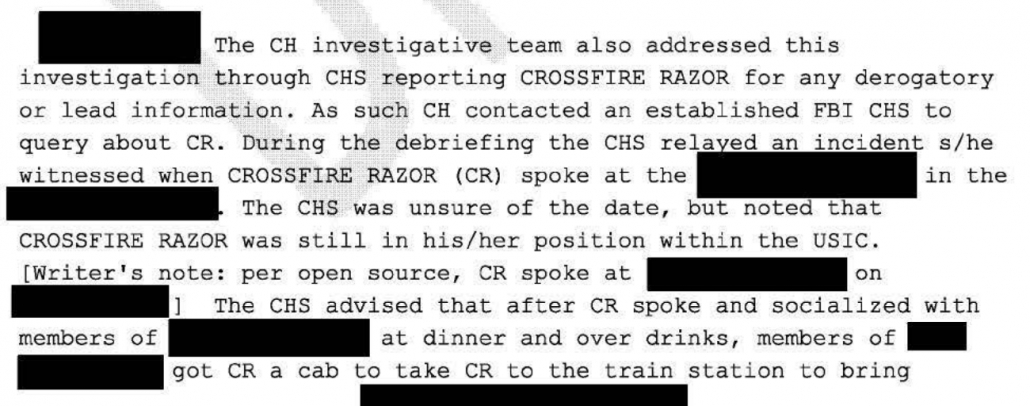

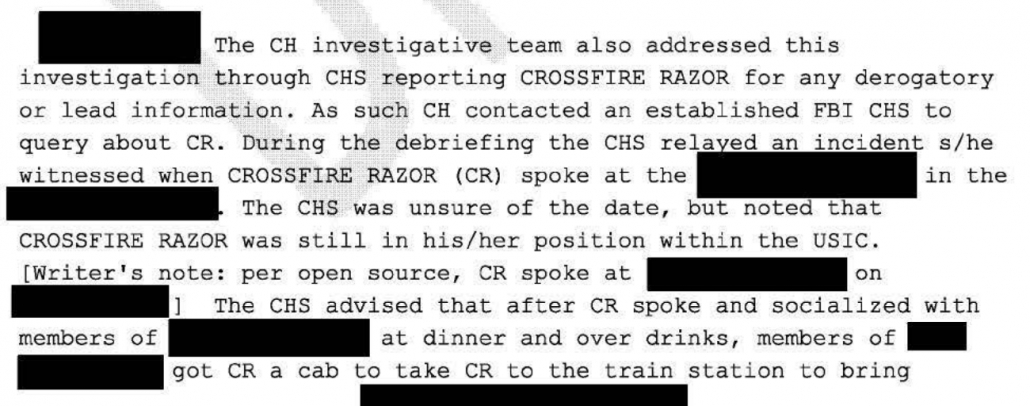

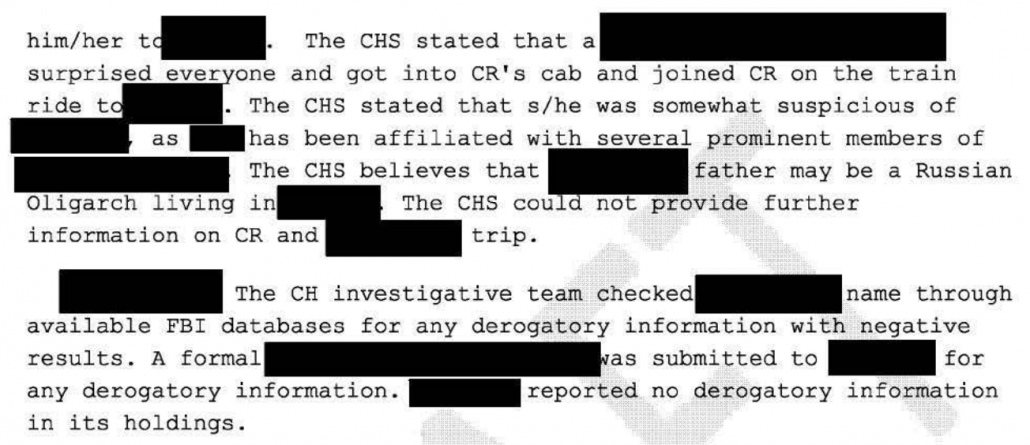

The draft closing document that Glenn himself thinks is a smoking gun only describes one stream of CHS reporting that came in on Flynn — which likely is that of Halper. That stream amounted to very little, was not reported before Halper was asked (contrary to claims Sidney Powell has made), and if this is Halper, the lead was chased down and dismissed.

That is, either FBI didn’t even consider Lokhova, or if they did, they didn’t give it any credence, the exact opposite of what Glenn claims happened.

Glenn also made an argument about Maria Butina in there, which I’ve dismantled when Matt Taibbi made it.

Claim without evidence: Barack Obama disliked Flynn

Amid a section laying out what a staunch critic of Obama Flynn was, Glenn also claims that Obama strongly disliked Flynn.

It’s really not an overstatement to say that President Obama after a very short period of time couldn’t stand Michael Flynn, Michael Flynn is exactly the kind of general and exactly the kind of official that President Obama strongly dislikes. And the feeling was very mutual.

[a very very long-winded presentation of how Flynn feels about Obama but not vice versa]

What was important and what is important for the subsequent events is the fact that President Obama seethes but seethes with contempt for General Flynn and the feeling was very mutual.

I know of no evidence to support this. Public reports show Flynn was fired for performance reasons, and most accounts say that James Clapper made the decision.

False claim: Flynn worked for “interests connected to the Turkish government”

In a passage on Flynn’s consulting work, Glenn misrepresents what Flynn himself has said about the work.

And they represented numerous clients as people who leave the military and intelligence world often do, including foreign governments, including interests connected to the Turkish government, and that consulting work that General Flynn did at times was not properly disclosed, as it is very common for consultants not to disclose their work. But that was the work that he was doing between 2014 when he left the Obama administration and 2016 in the middle of 2016 when he became an important surrogate for the Trump presidential campaign.

This passage suggests that Flynn did not work directly for the Turkish government and did that work before he became a chief surrogate for Trump.

The record shows the engagement with Ekim Alptekin started in late July, after Flynn had already figured prominently in Trump’s convention. Just days before Flynn sat in on Trump’s first classified briefing, he responded to an email from Alptekin describing his meetings with two Turkish ministers on the project by saying, “Thank you Ekim for your kind update. This is an important engagement and we will give it priority on our side.” Alptekin responded by describing his meeting with the two Turkish ministers and stating, “I have a green light to discuss confidentiality, budget and the scope of the contract.”

Moreover, unless Flynn perjured himself before the grand jury, he was not just working for “interests connected with the Turkish government,” he was working for the Turkish government.

I think at the — from the beginning it was always on behalf of elements within the Turkish government.

Of particular note, one of the lies Flynn told Covington as they prepared his FARA filings was that he wrote the November 8 op-ed published under his name as part of an effort to boost the Trump campaign’s war on terror cred. In reality, Flynn did not write the op-ed at all, he simply put his name to it.

Date and substance problems describing the sanctions

In a long passage in which Glenn suggests Russian interference isn’t proven, Glenn also muddles a lot of the facts regarding Flynn’s calls with Sergey Kislyak.

On December 29, President Obama, the Obama administration announced a new series of sanctions, as well as the expulsion of various diplomats aimed at Russia in order to punish Russia for what the Obama administration said was Russia’s interference in the 2016 election. It was Obama’s last one of his last acts on the way out the door was to give Democrats what they wanted by sanctioning Russia, imposing imposing new sanctions on Russia and expelling Russian diplomat as retaliation or punishment for what they claim was Russian interference in the 2016 election. [my emphasis]

Both the GOP-led House Intelligence Committee and the GOP-led Senate Intelligence Committee have issued reports confirming the Intelligence Community’s assessment that Russia interfered in the election. And yet Glenn here suggests this was just an empty Obama Administration claim.

Moreover, Glenn misrepresents the full basis for the sanctions, which also retaliated for escalating Russian harassment of US diplomats in Russia.

And while it’s a minor issue, Glenn gets the date of the sanctions wrong. They were first reported on December 28, which is important because Kislyak reached out to Flynn on that day, not the other way around (the timing of this is central to problems with the story Flynn told, which was designed to hide his consultations with people at Mar-a-Lago), as did someone from the Russian Embassy.

Elaboration: Claims about the conversation

In his description of the actual calls between Flynn and Kislyak, Glenn elaborates on the public record, suggesting Flynn talked about what might happen after Inauguration with regards to sanctions (rather than just setting up a call and attending a conference in Astana).

Once the Obama administration announced the sanctions and the expulsion of diplomats, General Flynn, ready to take office as National Security Adviser, called the Russian ambassador to the United States Sergey Kislyak on two separate occasions on that day, December 29. When these new reprisals were announced, essentially to tell him Look, there’s no reason for you to overreact. There’s no reason for you to retaliate. We’re about to take office in three weeks, we’re going to improve relations with you, we’re going to have a whole new relationship, so there’s no reason for you to do anything now that will force us in turn to retaliate. He was essentially trying to tamp down tensions to lay the groundwork for one of President Trump’s President Elect Trump’s campaign promises and foreign policy objectives which was to improve relations with Russia,

While it’s possible this is the way the call occurred, it’s not supported by the public record. The Mueller Report describes the conversation this way:

With respect to the sanctions, Flynn requested that Russia not escalate the situation, not get into a “tit for tat,” and only respond to the sanctions in a reciprocal manner.1250

The detail that Flynn suggested Russia respond “in reciprocal manner” is important because Russia did even less than that.

While Glenn says there were two calls between Flynn and Kislyak, he doesn’t describe the second one from these days, which is critical background to why the FBI focused on Flynn because of the calls. The Mueller Report describes it this way:

On December 31, 2016, Kislyak called Flynn and told him the request had been received at the highest levels and that Russia had chosen not to retaliate to the sanctions in response to the request. 1268

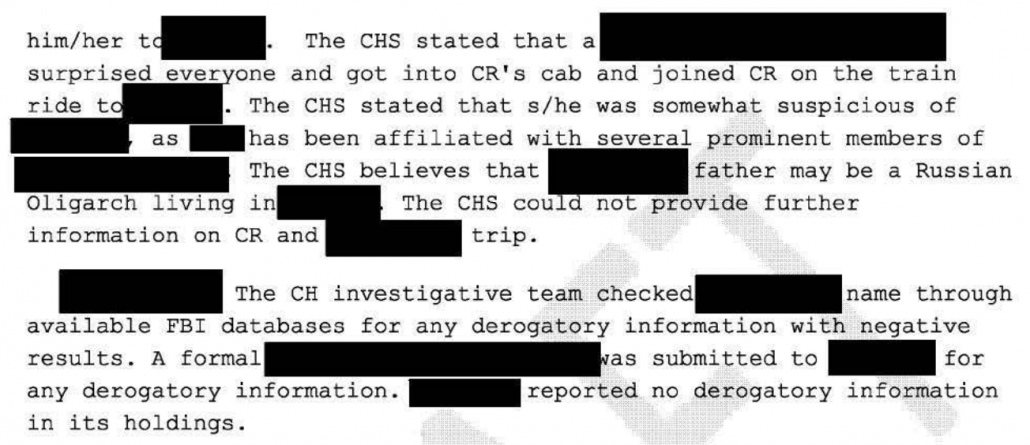

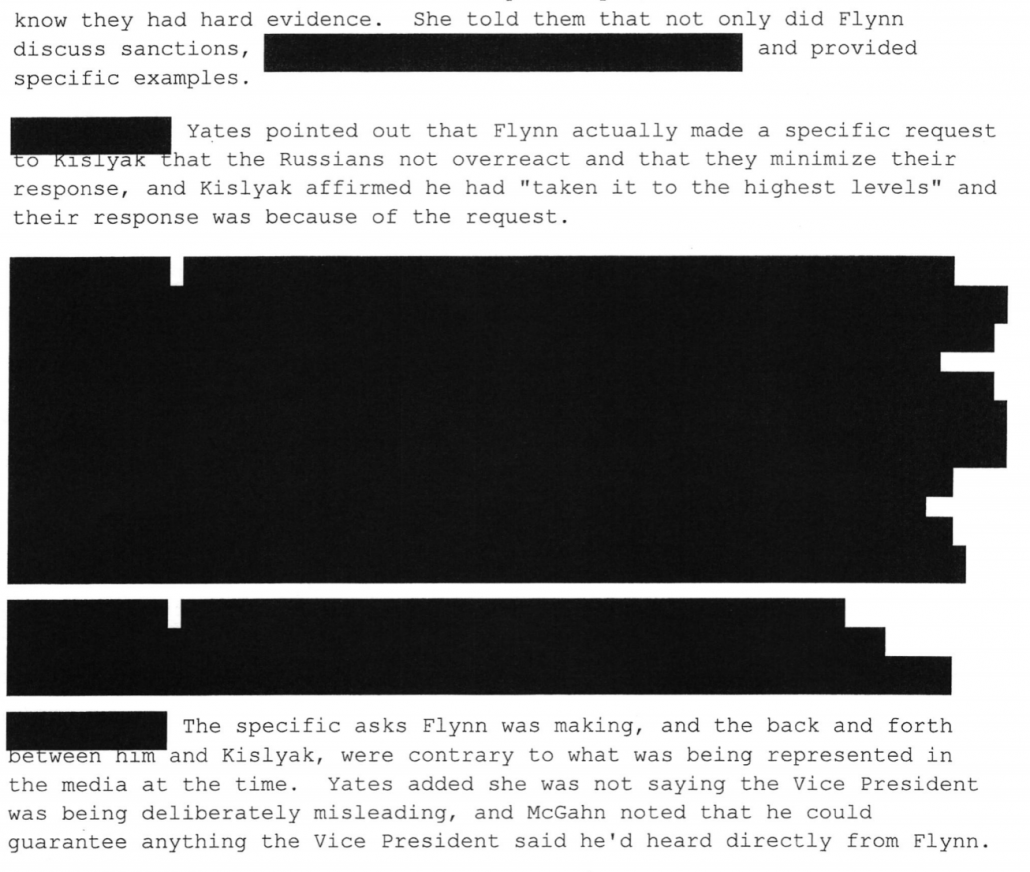

The transcripts themselves remain classified, as do Sally Yates’ descriptions of what was most alarming about these transcripts.

So we don’t yet know why reading the transcripts rather than hearing about the call elicited strong reactions from those who did read them, but they did, including not just people in the Deep State, but also Reince Priebus and Mike Pence.

Misrepresentation: It is normal for incoming National Security Advisors to reach out to their counterparts

Glenn correctly claims that it is normal for incoming national security officials to reach out to their counterparts. It is! He doesn’t say what made Flynn’s actions unusual, which is what increased the urgency about them: the lies he told to others within the Administration about the calls.

It is extremely common for transition teams and for national security officials who are incoming and an administration to reach out to their counterparts to try and create a new positive relationship. And that’s what General Flynn did by twice calling Ambassador Kislyak, whom he had known from his experience working as director of the CIA, the Defense Intelligence Agency on December 29. Now those two conversations that General Flynn had with Ambassador Kislyak were being monitored and recorded by the National Security Agency something that is extremely common is standard practice, as General Flynn knows and knew, because the NSA monitors and records the calls of as many officials as they possibly can, particularly in governments they consider to be adversarial such as Russia.

For some reason (perhaps so Glenn can liken surveilling US-based foreign officials with surveilling allies overseas) Glenn claims NSA picked up this intercept. FBI did.

But his silence about what makes Flynn’s actions here is utterly inexcusable: Flynn lied about what he had done to Mike Pence and others, which raised real questions at FBI about whether he was freelancing when he made the call (which might rightly be regarded as damage to Trump). As Mary McCord testified, that’s what made these calls different.

It seemed logical to her that there may be some communications between an incoming administration and their foreign partners, so the Logan Act seemed like a stretch to her. She described the matter as “concerning” but with no particular urgency. In early January, McCord did not think people were considering briefing the incoming administration. However, that changed when Vice President Michael Pence went on Face the Nation and said things McCord knew to be untrue. Also, as time went on, and then-White House spokesperson Sean Spicer made comments about Flynn’s actions she knew to be false, the urgency grew.

Note, too, some other small details here. Flynn knew Kislyak from paying a call before his RT gala trip; he denied any memory of meeting him in connection with his trip to Russia sponsored by the GRU. But he also made calls to Kislyak during the election that he attributed to condolence calls, which is the same excuse he used to claim his December calls weren’t about undermining US policy. It’s not public whether those other calls match Flynn’s claimed explanations for them.

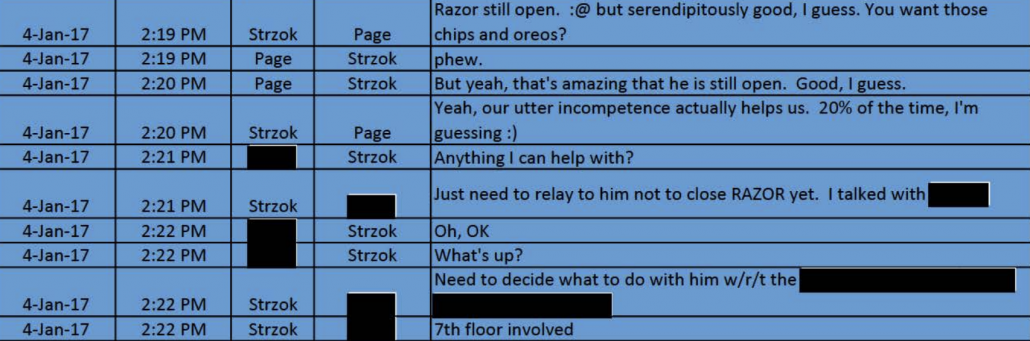

False claims: Strzok and Page talked about needing to impede Trump and “discovered” these transcripts

Glenn next tells a story of the discovery of the Flynn-Kislyak transcript where the villains of his story play the central role, actually trolling through the FBI collections and discovering the conversations.

The NSA was spying on so General Flynn obviously knew and he later told the FBI that he knew that those conversations were being monitored or recorded, but they were being monitored and recorded because the NSA had successfully obtained access to Ambassador Kislyak’s communications knowledge of those two telephone calls that Michael Flynn had with Ambassador Kislyak made its way to two particular officials with the FBI, Peter Strzok, and Lisa Paige, who became very controversial later on both because they were having an affair with one another, an extramarital affair, but more importantly, because there were all kinds of email exchanges between the two throughout the 2016 presidential election as they were participating in the investigation of the Trump campaign, where they were explicitly talking about the need to make certain that Donald Trump lost and then the need once he won to impede him to damage him and to try and undermine him anyway that they can. So it was these two FBI officials who discovered these conversations that General Flynn had with Ambassador Kislyak.

There are a lot of small details here that Glenn gets wrong.

As noted, the calls were monitored by FBI, not NSA (which is not a significant difference but notable since Glenn and Snowden conflate foreign intelligence and domestic law enforcement).

The FBI discovered the calls because the IC was trying to figure out why Putin didn’t respond as expected.

And so the last couple days of December and the first couple days of January, all the Intelligence Community was trying to figure out, so what is going on here? Why is this — why have the Russians reacted the way they did, which confused us? And so we were all tasked to find out, do you have anything that might reflect on this? That turned up these calls at the end of December, beginning of January.

There’s not a shred of reason to believe that Strzok or Page “discovered” these conversations (Comey says analysts did).

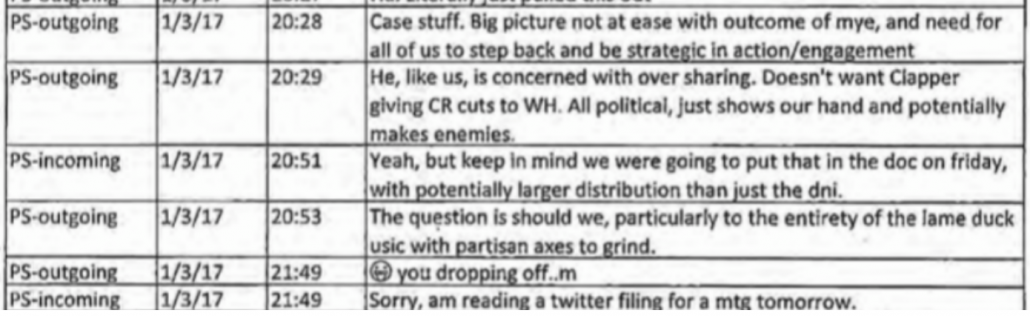

I assume Glenn’s descriptions of the emails about “making certain Trump lost” are some text, not email, exchanges explained at length in the Midyear Exam IG Report. The most damning text dates to August 8, 2016, shortly after Crossfire Hurricane was opened.

“[Trump’s] not ever going to become president, right? Right?!” Strzok responded, “No. No he’s not. We’ll stop it.”203

Another damning text dates to August 15, 2016, recounting a dispute in Andy McCabe’s office about how aggressively to conduct the Crossfire Hurricane investigation.

“I want to believe the path you threw out for consideration in Andy’s office—that there’s no way he gets elected—but I’m afraid we can’t take that risk. It’s like an insurance policy in the unlikely event you die before you’re 40….”

Importantly, Strzok lost his bid to investigate more aggressively during the election, just like he lost his bid to investigate Hillary as aggressively as possible. While these are utterly damning (even with Strzok’s explanations of them), as the later IG Report made clear, the report concluded — having read all the Page and Strzok texts — neither Strzok nor Page were in a position to unilaterally make decisions.

The only known text that might remotely suggest either was trying to “impede him to damage him” pertains to a discussion about whether Strzok should join the Mueller investigation. In it, he said he didn’t think there was much there.

“For me, and this case, I personally have a sense of unfinished business. I unleashed it with MYE. Now I need to fix it and finish it.” Later in the same exchange, Strzok, apparently while weighing his career options, made this comparison: “Who gives a f*ck, one more A[ssistant] D[irector]…[versus] [a]n investigation leading to impeachment?”204 Later in this exchange, Strzok stated, “you and I both know the odds are nothing. If I thought it was likely I’d be there no question. I hesitate in part because of my gut sense and concern there’s no big there there.”

If Glenn is relying on this (he didn’t cite anything), Glenn claims that a text showing that the guy whose goal (he says) was to impede Trump didn’t think there was much implicating Trump, and he uses that as proof he was out to sabotage Trump. It seems, instead, to be proof that Strzok didn’t let his view of Trump cloud his assessment of the evidence, a conclusion backed by other known details of the investigation.

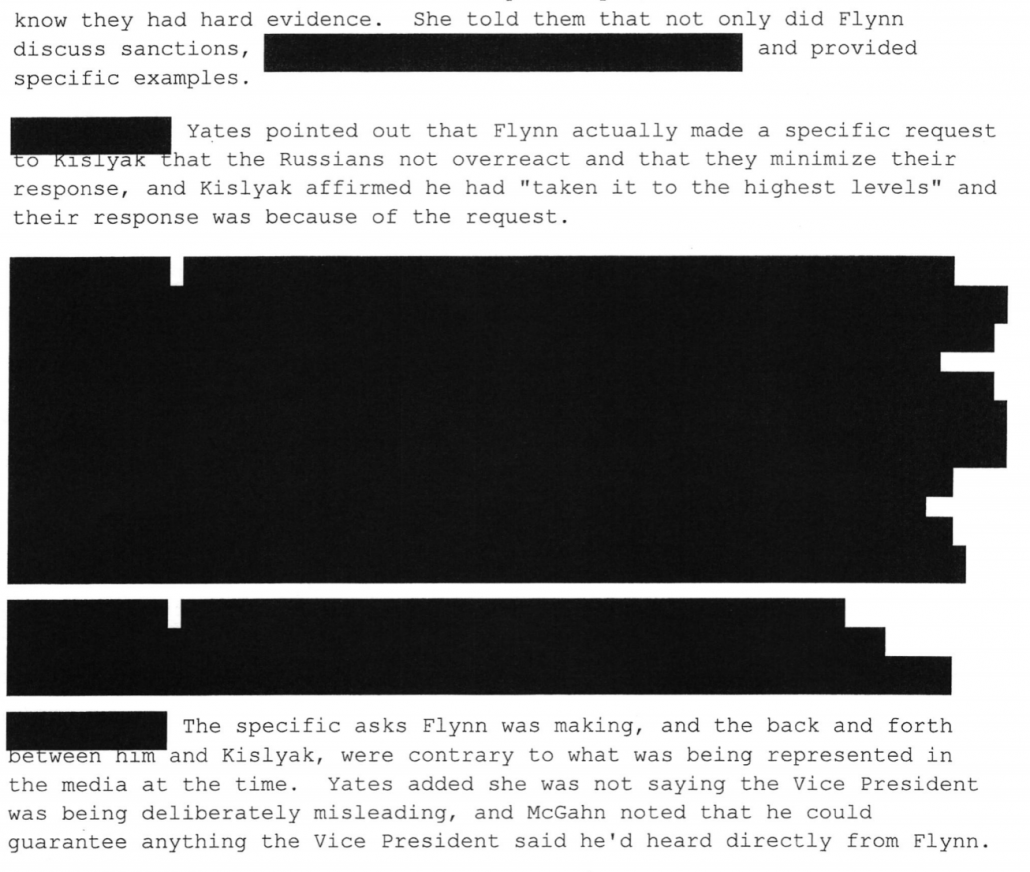

False claim: Lisa Page and Peter Strzok decided to keep the investigation into Flynn open

Glenn’s interpretation of the texts showing Strzok’s actions, especially, claims both that Comey didn’t want to investigate Flynn and did want to. At first, for example, Glenn suggests that Comey had ordered — rather than authorized — the closure of the investigation. It suggests some “snafu” rather than bureaucratic lassitude delayed the closure. And it suggests the Page and Strzok led this decision-making.

James Comey and the leadership of the FBI had decided to close the only pending investigation that the FBI had into General Flynn, which was part of the Operation Hurricane investigation, the investigation about improper ties between the Trump campaign and the Russian government James Comey and the FBI leadership concluded there was no evidence to believe that General Flynn had any improper contacts or connections with let alone had conspired with the Russian government during the election and as ordered that investigation closed and filed the paperwork in early January. But when Peter Strzok and Lisa Page got hold of these conversations that Ambassador Kislyak had had with General Flynn and decided they wanted to investigate him for it and use it against him, they discovered in early January that the order that James Comey and FBI leadership had given to close the investigation against Michael Flynn never was finalized because of a bureaucratic snafu. That investigation contrary to the decision that the FBI had remained open and what the newly discovered documents reveal, among other things, is that Peter struck and Lisa page celebrated. The bureaucratic snafu was good luck because it meant that there was now a still a pending investigation that was supposed to have been closed into General Flynn, who they could latch on to and hook on to in order to try and investigate him. Now because of these new conversations that he had with Ambassador Kislyak.

Comey testified that he authorized — not ordered — the investigation to be closed.

At that point, we had an open counterintelligence investigation on Mr. Flynn, and it had been open since the summertime, and we were very close to closing it. In fact, I had — I think I had authorized it to be closed at the end of January, beginning — excuse me, end of December, beginning of January. And we kept it open once we became aware of these communications. And there were additional steps the investigators wanted to consider, and if we were to give a heads-up to anybody at the White House, it might step on our ability to take those steps.

[snip]

MR. COMEY: To find out whether there was something we were missing about his relationship with the Russians and whether he would — because we had this disconnect publicly between what the Vice President was saying and what we knew. And so before we closed an investigation of Flynn, I wanted them to sit before him and say what is the deal?

The part of the texts that Glenn relies on to say Page and Strzok celebrated the case hadn’t been closed makes it clear that incompetence, not any snafu, had delayed the closure. It also makes clear that these decisions were coming from the 7th floor (that is, McCabe or Comey).

Other critics of these actions rely on that 7th floor detail to substantiate their claim of a great plot, but even imagining there was one, it would mean Page and Strzok don’t have the decisive role Glenn says they did.

Misrepresentation: Jim Comey wanted to investigate a person rather than a call

Both in the above passage and a following one, Glenn suggests that the existence of these calls was used as excuse to investigate Flynn, rather than the existence of transcripts showing the incoming NSA altering Putin’s behavior would always be reason to investigate.

James Comey wanted to investigate General Flynn. He wanted to do what he could use these newly discovered calls Against General Flynn, but the Justice Department then led by acting director, acting Attorney General Sally Yates, believe that it was improper to investigate what was about to be a high level White House official without notifying the Trump transition team and then the Trump White House that the FBI was investigating what was seemed to become a very high level official, and they thought about it and they thought about it until James Comey without notifying the attorney general or the Justice Department officials who were opposed to it sent FBI agents to general Flynn’s office with the intention of questioning him about the telephone calls that he had with the Russian ambassador,

As the texts above make clear, at first no one knew what to do about these calls.

Once again, Glenn doesn’t mention the role of Flynn’s lies to Mike Pence in leading everyone, including DOJ, to treat the transcripts differently.

MR. COMEY: To find out whether there was something we were missing about his relationship with the Russians and whether he would — because we had this disconnect publicly between what the Vice President was saying and what we knew. And so before we closed an investigation of Flynn, I wanted them to sit before him and say what is the deal?

As Yates described it, things heated up after it became clear Flynn had lied.

In early January, DOJ began to “ramp up” their discussions regarding Flynn, in reaction to a David Ignatius column describing the phone calls in early January 2017, followed by a statement where Sean Spicer around January 13, in which Spicer denied there was sanctions talk on the calls and stated that the Flynn calls were logistical. The false statement by Spicer, which Yates assessed to be the White House “trying to tamp down” the attention, caused DOJ to really start to wonder what they should do.

On January 13, 2017, things “really got hot.” On that day, Vice President Pence was on Face the Nation and stated publicly he’d spoken to Flynn and had been told there had been no discussion of sanctions with Kislyak. Yates recalled she was in New York City that weekend, and received a call from McCord notifying her of the statements. Prior to this, there had been some discussion about notifying the White House, but nothing had been decided. Until the Vice President made the statement on TV, there was a sense that they may not need to notify the White House, because others at the White House may already be aware of the calls.

There are redactions in Yates’ testimony that likely hide critical details. But Yates did concede that,

Generally, when the Intelligence Community learns of a “criminal investigation,” their reaction is to back off and defer to the FBI; [redacted] Yates did not herself believe the investigation would be negatively impacted, but Brennan and Clapper backed off after their talk with Comey.

False claim: The FBI made Flynn tell lies he wasn’t already telling

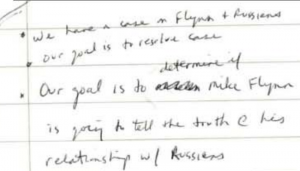

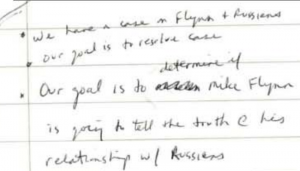

Glenn then turned to Bill Priestap’s notes, quoting from the part that reflects a rethinking about whether they should share Flynn’s own words with him, rather than the part that lays out the overall goal of the interview.

The day that FBI agents including Peter Strzok were sent to General Flynn to interrogate him about the calls that he had with General Kys — Ambassador Kislyak, and those handwritten notes made clear that the FBI was overtly flirting with an entertaining if not outright, executing an interrogation with corrupt and improper motives specifically to purposely induce General Flynn to lie to them so that they could use those lies to then punish him or turn him into a criminal to handwritten notes from the FBI official Bill Priestap specifically explicitly state quote, what’s our goal truth slash admission or to get him to lie so we can prosecute him or get him fired? This is revealing that the FBI had no real interest in interviewing General Flynn about what he said to Ambassador Kislyak because they already knew what he said since they had the transcripts of those conversations the result of the surveillance that was done on those calls, the only conceivable objective to go and interview him was to purposely induce him to lie not show him those transcripts, asked him what he talked about in that conversation that he had almost a month earlier, and the hope of getting him to lie so that they could get him fired. Not exactly a legitimate FBI objective, or turn him into a criminal create a new crime by using their power of interrogation to induce him to lie and then charged him with lying to the FBI. Whatever the ultimate motive was, these notes are highly incriminating about what the FBI’s real intentions were.

Again, Glenn said nothing about Flynn’s lies to Pence, which undermines the claims Glenn makes here. The public record at the time supported a suspicion that Flynn had gone rogue in his call to Kislyak, and was hiding what he had done with the Administration. Indeed, the public record still claims that Trump did not instruct Flynn to take these actions (though he applauded them after the fact).

That background is particularly important because the notes are consistent with several other contemporary pieces of documentation, including what Bill Priestap told Mary McCord contemporaneously and what Comey said a few months later. which show the purpose of the interview was to see whether Flynn would be honest about his conversations with Russia, particularly in light of Flynn’s apparent lies to Mike Pence and Sean Spicer.

That’s the very same purpose for the interview laid out in the second sentencing memorandum approved by Bill Barr’s DOJ just months ago.

And Glenn ignores how those notes also show that FBI backed off its initial plan not to share any details from the transcripts, but instead to quote his words back to him, effectively sharing the content of it. The 302 shows that the FBI Agents did that. In one instance, Flynn even thanked the FBI Agents for their reminder.

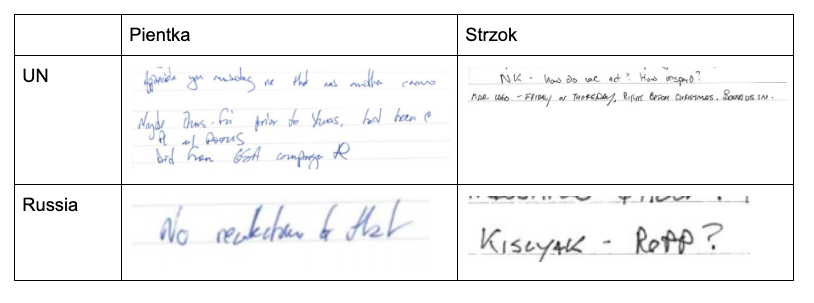

The interviewing agents asked FLYNN if he recalled. any discussions with KISLYAK about a United Nations (UN) vote surrounding the issue of Israeli settlements. FLYNN quickly responded, “Yes, good reminder.” On the 22nd of December, FLYNN. called a litany of countries to include Israel, the UK, Senegal, Egypt, maybe France and maybe Russia/KISLYAK.

But each time they did so with respect to Russia, the 302 shows, Flynn lied.

The interviewing agents asked FLYNN if he recalled any conversation with KISLYAK in which the expulsions were discussed, where FLYNN might have encouraged KISLYAK not to escalate the situation, to keep the Russian response reciprocal, or not to engage in a “tit-for-tat.” FLYNN responded, “Not really. I don’t remember. It wasn’t, ‘Don’t do anything.'” The U.S. Government’s response was a total surprise to FLYNN.

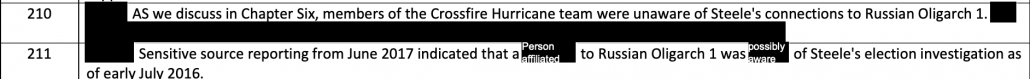

Glenn also utterly and hilariously misrepresents what happened between that initial interview, the investigations that revealed conversations with Mar-a-Lago that Flynn had lied about in the interview, and when Flynn accepted a plea deal in November 2017 because he faced up to 15 years on the Foreign Agent charges.

Conflation of the leak that the Steele dossier had been briefed and the sharing of the Steele dossier

Glenn then moves onto the Steele dossier, suggesting that the person who leaked a detail from Trump’s briefing had the intent of leading BuzzFeed to publish it, and conflating the public reporting on Trump with the FBI’s investigation of him.

CNN and CNN on January 10, reported that the director of the FBI had gone and briefed President Elect Trump to inform him of highly compromising information in the hands of the Kremlin. But this but CNN said that they weren’t going to describe the nature of that compromising information because they hadn’t been able to vet it or determine whether or not it was really true. But that was a limitation that BuzzFeed quickly decided that they were not going to be constrained by him so very predictably, and almost certainly intentionally from the perspective of whoever leaked this briefing. BuzzFeed then published what is now called the Steele dossier. And that forever altered the course of “Russiagate” [sic]those allegations those scurrilous and ultimately unproven allegations in the Steele dossier. About the Kremlin holding blackmail information over Trump about the sexual and the financial nature and all of the other highly inflammatory inflammatory material ended up shaping what became “Russiagate” [sic] and at least the first two to three years of the Trump presidency leaked by the very, very same people who were in the process of now exploiting the failure to close the Flynn investigation to also investigate.

Glenn seems to insinuate here that FBI leaked the Steele dossier to Buzzfeed. David Kramer did (and in fact, FBI didn’t have one of reports in the dossier that got leaked yet, so they couldn’t have leaked it).

His claim that the Steele dossier changed the Russian investigation is precisely the claim Paul Manafort started pushing after meeting a top Deripaska aide in Europe in early 2017, suggesting that was the point if the dossier was Russian disinformation. But there’s a difference between saying that the dossier was the basis of public reporting on Trump — in the same way that Clinton Cash was the basis of public reporting on the Clinton Foundation — and saying it drove the FBI’s work in the wake of its leak.

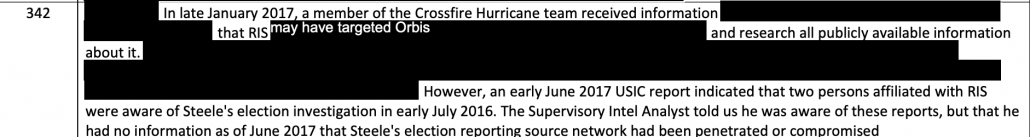

It is clear that the FBI used the Steele dossier to establish probable cause in the Carter Page applications even after it learned information that should have led it to stop. The FBI also used the publication of the dossier as an excuse to interview George Papadopoulos. But there’s no basis to believe it impacted the others, including Flynn. For example, the draft closing document on Flynn only made one reference to a CHS (which is how FBI treated Steele) and it clearly wasn’t a reference to Steele. And the predication of the investigation into Michael Cohen made no mention of the dossier, even though the most inflammatory claims in the dossier were about him.

So while the dossier may have mattered to Glenn and other people not actually following the evidence closely, aside from the very notable example of the Carter Page FISA application, the FBI primarily used it as an excuse to interview George Papadopoulos. For everyone else, there’s no evidence it played a big role.

Claim without evidence: David Ignatius should go to prison for his Kislyak leak

In his treatment of the inexcusable leak to David Ignatius, Glenn suggests that leak was more criminal than anything else (even though Glenn himself has published such information), claiming that someone leaked “NSA intercepts.”

The Washington Post David Ignatius, who has built a career, receiving leaks from the CIA and publishing what the CIA wants him to publish published a column in which he revealed for the first time that the NSA had monitored the conversations between General Flynn on the one hand and Ambassador Kislyak on the other and after that, the contents of the communications between General Flynn Ambassador Kislyak were elite to both the Washington Post and the New York Times, which published in detail what those communications were. Now the reason that’s so striking is because under the law, it is a crime, obviously, to leak classified information of any kind, any information that’s classified, if somebody inside the government leaks it to a journalist, that’s a crime. But there’s only a narrow number of types of information that can become a crime for the journalists to actually publish it. The most serious kind of information is not only a crime for that leaker to leak to the journalists, but for the journalists to publish it. And one of those types of information is exactly the type that people inside the intelligence community leaked in order to destroy the reputation of General Flynn, namely intercepts by the NSA, of the communications of foreign officials. And the reason that the intelligence community in the law regards leaks of that type. So grave is such a grave offense is obvious because it has the potential to ruin the ability of the NSA to continue to monitor that information by alerting the adversary that they have access to that communication. If you look at the relevant law, which is title 18 of the US Code Section 798 that specifies when it’s a crime not just to leak classified information, but for a journalist to publish it. It specifies exactly the kind of information that people inside the government are leaking against General Flynn that’s how far they were willing to go that law reads quote, whoever knowingly and willfully communicates or otherwise makes available to an unauthorized person or publishes any class government shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than 10 years, or both. Now, you can see it explicitly provides that the crime is not just leaking. But publishing it’s one of the few types of leaks where you can actually criminalize the journalist now I’m against this law.

As noted above, these were FBI intercepts (though that likely doesn’t change the Espionage Act analysis).

I don’t defend the leak to Ignatius (and raised questions about it contemporaneously). But it’s important to note several things: it is sourced in a way — senior US government official — that could be second-hand (which is what Comey seemed to believe), could be an Original Classification Authority (Flynn’s team has accused James Clapper of the leak), which would not actually be a leak or illegal — it would be directly equivalent to many of the releases Ric Grenell has recently made — or could be a member of Congress. Glenn accused a vague “they” of leaking it with no evidence that the FBI did it.

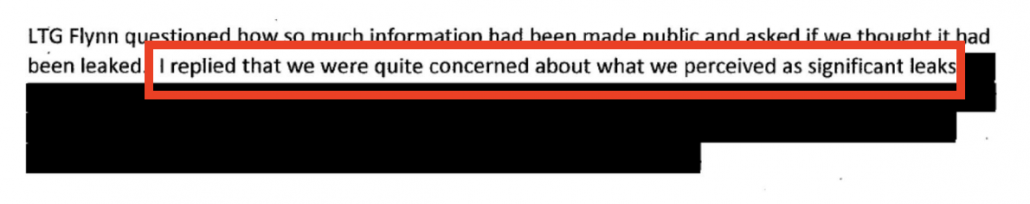

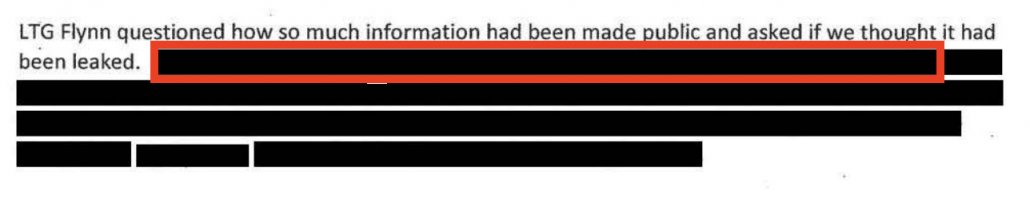

Indeed, one thing Barr’s DOJ reclassified in the motion to dismiss is a detail from McCabe’s notes of his call with Flynn reflecting real concern about the leaks.

This was first shared with Judge Sullivan in unredacted form when he took Flynn’s plea in December 2018. This version is, in some respects, more classified than a version released last May. For example, last May DOJ revealed that McCabe agreed with Flynn that leaks were a problem.

Today’s version redacts that line as classified.

Similarly, the frothy right has totally misrepresented Strzok and Page’s concerns about the leak of Carter Page’s FISA order.

Also, there’s nothing in the Ignatius column that necessarily proves he got the content of the call, which is a closer case than Glenn makes out here under 18 USC 798.

According to a senior U.S. government official, Flynn phoned Russian Ambassador Sergey Kislyak several times on Dec. 29, the day the Obama administration announced the expulsion of 35 Russian officials as well as other measures in retaliation for the hacking. What did Flynn say, and did it undercut the U.S. sanctions? The Logan Act (though never enforced) bars U.S. citizens from correspondence intending to influence a foreign government about “disputes” with the United States. Was its spirit violated? The Trump campaign didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment.

Glenn has published a great deal of information that would violate this law, claiming it served the public interest. He is here substituting his judgment for Ignatius and the leaker in the same way others have questioned his and Snowden’s judgment.