Given recent news relating to Rudy Giuliani and Hunter Biden[‘s dick pics], I want to belatedly look at what Geoffrey Berman’s book, Holding the Line, says about the Lev Parnas investigation.

Berman’s memoir is, as all autobiographies are, a complex narrative. There are many reasons why that’s true in this case. We all tell ourselves and others false stories about ourselves, often as not unconsciously. There are one or two points in Berman’s story where he makes claims belied by publicly-released documents; I assume those are inadvertent, but they serve as interesting signposts of the limits of his own firsthand knowledge of particular matters. Someone with access to classified or confidential information will be forced, as Berman seems to have been, to either nod to or entirely avoid big parts of the story, probably a really big factor in the matters I write about below. And finally, famous, powerful people shade the truth for posterity and to hide inconvenient truths. There’s a whole bunch of that in this book, a long form effort to pitch his association with the Trump Administration, not unfairly, as a worthwhile opportunity to do a lot of important work holding sex traffickers accountable (including, but not limited to, Jeffrey Epstein) and in key moments, protecting investigations from the interference of all three of Trump’s Attorneys General.

How Berman tells this story — how anyone tells their autobiography — can say as much as the facts relayed.

The most fascinating narrative construction in Berman’s autobiography comes in his discussion of Bill Barr’s confirmation.

It appears immediately after Berman’s recounting of DOJ’s effort to force SDNY to prosecute John Kerry for interfering in Trump’s plan to overturn the Iran Deal. (The SDNY prosecutor in charge of that effort, Andrew DeFilippis, played the most abusive role on John Durham’s team and resigned unexpectedly before the Igor Danchenko trial, but that’s obviously not part of the story of what transpired at SDNY.) Given the timeline laid out in Berman’s book, in which SDNY’s investigation into Kerry lasted for about a year starting on May 9, 2018, that effort must have continued until May 2019. In fact, Berman ties pressure to bring charges from DOJ on April 23, 2019 with Barr: “By the time we got pressured in April 2019, on the same day as one of the Trump tweets, Bill Barr was the attorney general.”

From there, Berman shifts back in time to talk about the turnover at Attorney General. After a short anecdote about Matt “Big Dick Toilet Salesman” Whitaker trying to glom onto Berman’s good press in NY, Berman introduces Barr’s confirmation by suggesting polarization was the cause of Barr’s close confirmation vote in the Senate.

In one marker of how much more polarized our politics have become, Barr’s first confirmation hearing in 1991 was described at the time as “placid.” He was approved unanimously by the Senate Judiciary Committee, then confirmed by the full Senate in a voice vote. When Barr’s second nomination went before the Senate early in 2019, he was confirmed, but in a roll-call vote—with the 54–45 count mostly breaking down along party lines.

This was, of course, not a mark of polarization. It was a mark of Barr’s unsuitability to be Attorney General, and it was specifically attributed to his audition for the job in the form of a memo, seemingly based entirely on claims Barr picked up watching Fox News, attacking Mueller’s investigation, as well as his role in shutting down the Iran-Contra inquiry. Spinning the close vote, in a book released in 2022, as partisanship allows Berman to suggest that the close vote wasn’t entirely justified. That, in turn, makes the insipid note Berman wrote welcoming Barr to the post (a note which presumably would be accessible under FOIA) less ridiculous.

I was elated that we were getting somebody to come in to take Whitaker’s spot, and I had high hopes. The new boss was experienced and highly intelligent. He had a reputation as an institutionalist, someone who would respect the traditions and norms of the department. Most of all, I believed Barr would be a steady hand in turbulent times.

I sent him a handwritten note, relating that in his first tour of duty he had signed my certificate when I started out as a young AUSA. I said we had never had an opportunity to meet, but I was looking forward to that soon.

I added that he was “just what the doctor ordered.” Like so many other establishment Republicans, I thought he would clean things up at DOJ and respect the rule of law.

Blech! Yick!

Then, immediately after describing this suck-up note, Berman describes the reason he, of all people, should have known better then to think Barr would “respect the rule of law”: because he knew, as someone who had worked on the Iran-Contra investigation, Barr’s past history interfering in an investigation of the President.

Berman tells a superb anecdote that I hope is not embellished about how, the only time Barr was in Berman’s office, the Attorney General saw a picture of Berman with Iran-Contra Independent Counsel Lawrence Walsh, on whose team Berman had worked very early in his career. As Berman describes (there’s an extended history of Iran-Contra in-between — go buy the book), Barr simply stared at the picture for a minute.

The one time that Barr met with me in my personal office at the Southern District involved an uncomfortable moment, and it was telling. It happened after he noticed a photo on the wall of me with Lawrence Walsh, the independent counsel in the Iran-Contra affair. It was signed, “Thank you Geoff, for all your good work.”

[snip]

That day in my office, Barr fixed his gaze on the picture of Walsh and me. He looked at it for almost a minute straight without saying a word. Just stared with a sour look on his face. It was awkward as hell. [my emphasis]

Only after describing what Berman suggests was an unfairly close confirmation vote, his own sycophantic note to Barr after it, and this exchange of indeterminate date, does Berman turn to what he calls (justifiably) a philosophical divide between him and Barr over the role of presidential power. After describing Barr’s November 2019 Federalist Society speech in which he falsely claimed that Presidential powers had been encroached over the years, Berman reviewed Donald Ayer’s June 2019 article explaining “why Bill Barr is so dangerous.”

There were critics—among them some lawyers who worked in prior Republican administrations—who felt that Barr soft-pedaled his views during the confirmation process and later acted in extreme ways on Trump’s behalf. One of them was Donald Ayer, a highly regarded lawyer who served in the administrations of Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush.

In a 2019 essay in The Atlantic, Ayer wrote, “In securing his confirmation as attorney general, Barr successfully used his prior service as attorney general in the by-the-book, norm-following administration of George H. W. Bush to present himself as a mature adult dedicated to the rule of law who could be expected to hold the Trump administration to established legal rules. Having known Barr for four decades, including preceding him as deputy attorney general in the Bush administration, I knew him to be a fierce advocate of unchecked presidential power, so my own hopes were outweighed by skepticism that this would come true.”

Ayer’s piece appeared after the release of the Mueller report, which many believed Barr had both preempted and misrepresented. Ayer continued, “But the first few months of his current tenure, and in particular his handling of the Mueller report, suggest something very different—that he is using the office he holds to advance his extraordinary lifetime project of assigning unchecked power to the president.”

Much of this political back-and-forth was beyond the scope of my concerns in the Southern District. I was a working prosecutor, and my focus was to lead the dedicated and hardworking public servants under me who came into work every day and busted their asses. My political views—and whatever my thoughts might have been on Barr’s high-altitude insights into the Constitution—were beside the point.

But the fact was, Barr’s top-down, unitary theories of power extended to how he viewed himself, how he ran the Justice Department, and how he felt about the people who worked for me. If Barr believed that the president could properly instruct the DOJ to take actions involving specific individuals, including his friends and enemies, that was a concern of mine. [my emphasis]

The narrative structure of this goes: Barr’s close February 2019 confirmation vote, Berman’s insipid note, the undated meltdown when Barr saw a picture of Berman with Walsh, Barr’s November 2019 discussion of views already evident in his June 2018 audition memo, and finally Ayer’s June 2019 description of the danger of Bill Barr, which had most recently been exhibited by his March 2019 response to the Mueller report. In sum, it provides a permissibly partisan frame in which to criticize Barr. But that jumbles the real timeline. Such a narrative structure allows Berman to introduce Barr’s authoritarian views in such a way as to absolve a former member of Lawrence Walsh’s team for writing a FOIAble letter claiming Barr was “just what the doctor ordered” around February 2019. It’s not that the Democrats were right to vote against Barr, the narrative allows Berman to suggest, it’s just that Ayer hadn’t written his condemnation of Barr yet.

And for some reason, Berman puts that exchange in his office, of indeterminate date, in the middle of it all. The single time, Berman says, that Barr visited Berman’s office.

It’s awfully curious that Berman doesn’t date that meeting, because Berman’s story of the Parnas and Fruman prosecution doesn’t describe the visit to SDNY that Barr was reported to have made, in real time, the day that Rudy’s flunkies were indicted — a visit to New York that also included a meeting with Rupert Murdoch. Berman actually tells the story of that day twice, first in conjunction with a contentious fight with Main Justice over whether SDNY must join in the effort to assume Trump’s defense in Cy Vance’s investigation, then in his telling of the Parnas and Fruman indictment. Both were going on at the same time. But in neither telling does Berman describe that the Attorney General showed up in New York, purportedly to meet with people like him and people who worked for him, at a time when Berman was in at least one really contentious fight with the Attorney General’s office.

Maybe Barr went to New York to visit SDNY and got lost at Murdoch’s place and so never showed up??

The Parnas and Fruman story, as told here, begins on October 8, when Berman got pulled out of Yom Kippur service to be told that Parnas and Fruman had just booked one way tickets to Europe.

What he told me was that Lev Parnas and Igor Fruman had just bought airline tickets for travel the next day to Frankfurt, Germany—one-way tickets—and we had to decide whether to arrest them before they boarded the plane.

As Berman described it no one else on the prosecution team supported indicting Rudy’s flunkies before they boarded a plane.

It was quickly apparent to me that I was in a minority of one. I would describe one call as almost like an intervention. I answered and six people were on the line: Audrey Strauss, the chief of the criminal division, Laura Birger, Chief Counsel Craig Stewart, Ilan Graff, Russ Capone, and Ted Diskant. Every one of them said we should let them travel.

Berman got the NY FBI Assistant Director, William Sweeney, to agree with him, and then (having apparently thus won the argument with the line prosecutors) the team worked overnight to complete the indictment, finishing (if I have my timeline correct) less than three hours before the announcement of Barr’s visit to NY.

Donaleski and Roos came into the office at about 11:00 p.m., and I joined them with coffee I had made at my apartment. (The local coffee shops were closed.) They drafted the indictment through the night, with review and revision by others either in the office or from home. Because the charges included campaign finance violations, we needed sign-off from the career attorneys at Main Justice’s Public Integrity Section. Diskant was on the phone with them at 4:00 a.m. and got the approval.

At 7:00 a.m., everyone came into the office for a final edit. At 9:00 a.m., the draft was finished, and [Rachel] Donaleski and [Nicholas] Roos went before the grand jury. By 2:00 p.m., they returned an indictment. Time to spare!

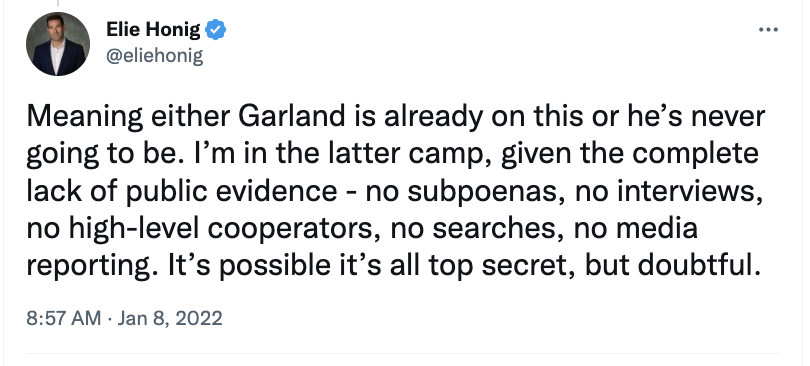

In a later post I’ll come back to that 4AM approval from Public Integrity. But note that Berman doesn’t describe getting approval from anyone else at Main Justice, even though after the indictment DOJ confirmed that Barr had been briefed from shortly after his confirmation. Just career attorneys at Public Integrity at 4AM.

Having told the heroic story of how prosecutors pulled together a last minute indictment, Berman then goes back and explains where the investigation came from. It came not from a referral from Federal Election Commission (which Republicans had made entirely dysfunctional at the time), but because SDNY’s Public Integrity section read the complaint that was submitted to the FEC.

Our public corruption unit monitors complaints filed with the FEC for possible investigation. Nick Roos read the complaint and persuaded Capone and Diskant to open the investigation. Roos and Donaleski began to put the pieces together. We confirmed that Global Energy was nothing but a shell with no business and no capital investment. Lev and Igor ran foreign money through it for the purpose of contributing to political candidates and committees in the United States.

The description of the part of the indictment relating to the firing of Marie Yovanovitch — the part of the indictment that was shelved in 2020 and which just died without charges — covers several pages. The first paragraph starts with a sentence — about the Russian donor behind some of the influence peddling — that should be in the prior paragraph. Then it lumps in the stuff implicating Rudy as a mere addition, almost an afterthought (probably necessitated, in part, by DOJ guidelines about uncharged persons).

[Andrey] Muraviev’s money was also used to donate to statewide races in Nevada. In addition, Lev and Igor contributed money, also through straw donors, to Pete Sessions, who at the time was a congressman from Texas and chairman of the powerful House Rules Committee. The outreach to Sessions was connected to their effort to get Marie Yovanovitch fired from her post as US ambassador to Ukraine. [my emphasis]

This is how it appears in the indictment:

In addition to the contributions made and falsely reported in the name of GEP, LEV PARNAS and IGOR FRUMAN, the defendants, caused illegal contributions to be made in PARNAS’s name that, in fact, were funded by FRUMAN, in order to evade federal contribution limits. Much as with the contributions described above, these contributions were made for the purpose of gaining influence with politicians so as to advance their own personal financial interests and the political interests of Ukrainian government officials, including at least one Ukrainian government official with whom they were working. For example, in or about May and June 2018, PARNAS and FRUMAN committed to raise $20,000 or more for a then-sitting U.S. Congressman (“Congressman-1”), who had also been the beneficiary of approximately $3 million in independent expenditures by Committee-1 during the 2018 election cycle. PARNAS and FRUMAN had met Congressman-1 at an event sponsored by an independent expenditure committee to which FRUMAN had recently made a substantial contribution. During the 2018 election cycle, Congressman-1 had been the beneficiary of approximately $3 million in independent expenditures by Committee-1. At and around the same time PARNAS and FREEMAN committed to raising those funds for Congressman-1, PARNAS met with Congressman-1 and sought Congressman-1’s assistance in causing the U.S. Government to remove or recall the then-U.S. Ambassador to Ukraine. [my emphasis, footnote omitted]

After a few paragraphs about Sessions’ excuses for deciding out of the blue that Yovanovitch should be fired, Berman describes that SDNY was still “exploring” whether this meeting might one day become a FARA charge.

The indictment made reference to this meeting with Sessions. It included an allegation that Lev, at the request of a Ukrainian official, had sought the removal of the US ambassador to Ukraine and had met with a congressman (Sessions) to solicit his support for the removal. We were still exploring whether these allegations might later form the basis of a FARA charge against Lev and others who, through lobbying or media appearances, sought the removal of Yovanovitch at the request of a foreign official without registering as a foreign agent.

As Berman describes it, when they included this Pete Sessions donation in the indictment (a footnote describes that the contribution was made under Fruman’s name, but misspelled), they were “exploring” the possibility that it might tie to illegal foreign influence peddling in part by “others who … sought the removal of Yovanovitch at the request of a foreign official without registering as a foreign agent.” Without naming Rudy yet, this passage suggests that they were only beginning to consider whether Rudy had committed a FARA violation when they prepared an indictment overnight on October 9 — with approval only from Public Integrity, not the FARA people in National Security Division who would one day get involved in the investigation — to arrest Rudy’s grifters before they flew to Europe.

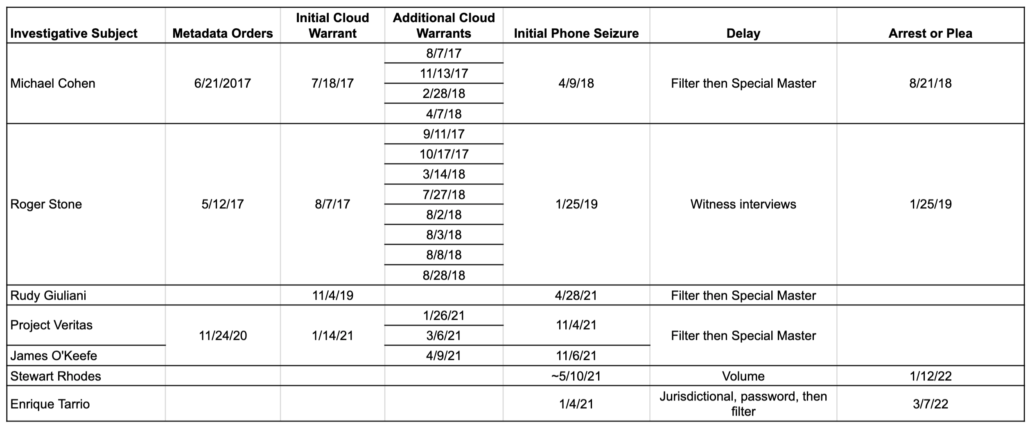

Remember: by November 4, less than a month later, SDNY got warrants targeting Rudy, investigating FARA, 18 USC 951, and conspiracy.

I wonder whether some of the prosecutors opposed arresting Parnas and Fruman because they wanted to see what would happen at the meeting with Dmitry Firtash and what other Ukrainian government officials were involved besides Yuri Lutsenko.

Some paragraphs later, after describing Rudy’s role in the Fraud Guarantee stuff (which was superseded later, in 2020, when the Yovanovitch firing was taken out), Berman acknowledges that Rudy had also been trying to get Yovanovitch fired, effectively confirming that Rudy was one of the “others who” had tried to get Yovanovitch fired.

Yovanovitch’s removal was a major goal of Giuliani’s—and of other Trump allies—who believed that she was an obstacle to their efforts to unearth damaging information about the then presidential candidate Joe Biden and his son Hunter. The ambassador was considered an anticorruption advocate, and some Ukrainian officials—including those working with Lev and Igor—wanted her moved aside.

And then, a few paragraphs after that, Berman acknowledges that Parnas and Fruman were some of the agents mentioned in the articles of impeachment alleged to be soliciting Ukrainian influence to help him get reelected, even while asserting “we had no role to play” in impeachment.

It was, of course, impossible for me or anyone else to be unaware of how politically charged all of this was. The nation was in the third year of Donald Trump’s combustible presidency, and the 2020 election cycle was underway. Two months after the indictment of Lev and Igor, the House of Representatives voted to impeach President Trump.

The first of the two articles of impeachment alleged that the president “solicited the interference of a foreign government” to take actions that would “benefit his reelection, harm the election prospects of a political opponent, and influence the 2020 United States Presidential election to his advantage.” The foreign government was Ukraine, and the reference to Trump’s being assisted by “his agents within and outside the United States Government” obviously would have to include Lev and Igor.

Impeachment is a political process. We had no role to play in it.

This passage is almost the entirety of any discussion in the entire book of the Ukraine impeachment. Berman makes no mention of the months of focus leading up to impeachment.

Of particular note, he makes no mention of the release of the Perfect Transcript in late September, less than two weeks before SDNY suddenly charged Parnas and Fruman. He doesn’t describe whether the release of the transcript alerted SDNY (if they didn’t already know) how some of the matters under investigation by SDNY — Parnas’ ask of Pete Sessions to help oust Yovanovitch — were centrally connected to the impeachment, with Trump raising them explicitly with Ukraine’s president.

I heard you had a prosecutor who was very good and he was shut down and that’s really unfair. A lot of people are talking about that, the way they shut your very good prosecutor down and you had some very bad people involved. Mr. Giuliani is a highly respected man. He was the mayor of New York City, a great mayor, and I would like him to call you. I will ask him to call you along with the Attorney General. Rudy very much knows what’s happening and he is a very capable guy. If you could speak to him that would be great. The former ambassador from the United States, the woman, was bad news and the people she was dealing with in the Ukraine were bad news so I just want to let you know that. The other thing, There’s a lot of talk about Biden’s son, that Biden stopped the prosecution and a lot of people want to find out about that so whatever you can do with the Attorney General would be great. Biden went around bragging that he stopped the prosecution so if you can look into it … It sounds horrible to me.

[snip]

Well, she’s going to go through some things. I will have Mr. Giuliani give you a call and I am also going to have Attorney General Barr call and we will get to the bottom of it. I’m sure you will figure it out. I heard the prosecutor was treated very badly and he was a very fair prosecutor so good luck with everything. [my emphasis]

Berman also makes no mention of the references to Barr that Trump made while trying to coerce Volodymyr Zelenskyy, including those bolded above. Each reference to Barr here appears in close proximity to Trump’s attacks on Yovanovitch, that part of the Parnas indictment that SDNY was “exploring” whether it constituted a FARA violation.

Berman makes no mention of any of that. “We had no role to play” in impeachment.

But all of that had to have been central considerations to the prosecution, not least on October 8 when Berman interrupted his Yom Kippur worship to engage in a debate about whether they should pull together an indictment to charge Parnas and Fruman before they left the country, and not just to pull together an indictment, but to include the traces of a Yovanovitch charge which (Berman admits here) they were “still exploring whether these allegations might later form the basis of a FARA charge against Lev and others.”

As he describes it, they just called some folks in Public Integrity at 4AM to get approval and included the Yovanovitch charge which could implicate the investigation that would become Trump’s first impeachment.

Way before this narrative of the case in the book, and then briefly afterwards, Berman describes how Barr’s Chief of Staff inquired before the arrest announcement (what would have been October 10) about what SDNY was going to do, then bitched out Berman after the fact because it got a whole lot of press attention.

A few hours before we were to announce the charges, Rabbitt asked me, “What are you planning to do for publicity for Lev and Igor?” I said, “I’m going to have a press statement,” and he said, “Okay. Fine.”

Later that day, we made our statement. It was in front of cameras, and it got huge coverage. When I got back to my desk, Rabbitt called me up, livid. “I thought you said it was going to be a press statement?” he barked.

I replied, “I didn’t take questions. It was a press statement. If it were a press conference, we would have had questions.” I thought that was perfectly legit, but Rabbitt wasn’t satisfied. The exchange with him was a little uncomfortable, but the Lev and Igor indictments came at a fortuitous time. (It just happened that way; we didn’t intend it and couldn’t have anticipated the international travel that prompted their arrests.) If Main Justice took action against me in any way, or even just got in a public flap, the media would have assumed it was retribution after we indicted these two individuals who moved in Republican circles. It would have played as blowback from the arrests.

After we got press attention on a big matter and our visibility was high, I always felt sort of bulletproof, at least temporarily. It gave me a couple more months of grace.

[Fifteen page break, including the description of the Parnas and Fruman indictment laid out above]

Except for the concern that we not have a press conference to announce the indictments, Main Justice and Barr did not interfere in the prosecution of Lev and Igor.

The longer description of the exchanges with Brian Rabbitt comes fifteen pages before the reference back to it. In context, the reference to being “bulletproof” seems to pertain to the conflict with Barr’s people over the Vance intervention. By the time we get through the description of the Parnas charges (which Berman put in an entirely different chapter), a reader might well have forgotten that Berman recognized a high profile press conference of the sort that Barr’s Chief of Staff complained about would make it harder to fire him.

But it all makes more sense when you consider the decision to indict Rudy’s grifters overnight with approval only from career officials who happened to be working at 4AM in Public Integrity. It all makes more sense when you think about the reported visit Barr made to SDNY that Berman never mentions (which, admittedly, may never have happened).

Berman’s brief reference back to that Rabbitt complaint appears immediately after he writes, “Impeachment is a political process. We had no role to play in it,” but in a new section. It kicks off a four page section, covering events starting in January 2020 and lasting (based on documents released under FOIA) well past March, describing efforts Barr made to stymie any further investigation from SDNY. Barr wasn’t so much trying to protect Rudy, Berman describes: he thought Barr viewed the President’s personal lawyer as a potential rival. Rather, the Attorney General was trying to prevent “tentacles” from reaching others.

Main Justice and Barr did not interfere in the prosecution of Lev and Igor.

[snip]

To the extent all of this tarnished Rudy, I think Barr was fine with it. But the case had tentacles. It raised other questions and suggested new areas of inquiry. It potentially led to other subjects. And Barr certainly did involve himself in those potentialities.

[snip]

He has no way of knowing where it might go—and really, nobody does—but it looks to him as if it has the potential to spiral. [my emphasis]

In the four pages following this introduction, Berman describes how Barr effectively prevented SDNY from going any further with their investigation, first by assigning the next steps of the Rudy investigation to EDNY (to Richard Donoghue, with whom Barr had tried to replace Berman to kill the Michael Cohen investigation, but who may have gone on to save the Republic on January 3, 2021). That reportedly had the effect of prohibiting SDNY from investigating Rudy’s meetings with Andrii Derkach, who was dangling dirt that closely resembled what would come to be known as the “Hunter Biden” “laptop.” Berman describes what likely is the Derkach investigation this way:

In addition, Donoghue, as part of his new role, was given a sensitive Ukraine investigation that I thought should have gone to us.

Then Berman describes Barr assigning the intake of Rudy’s dirt on Hunter Biden (though he doesn’t describe it as such) to Scott Brady in Pittsburgh.

I didn’t know Brady well, but I considered him a solid guy.

This post describes how that all worked, and pointed to some communications about it all that the Attorney General’s office seemed to have no longer available when they were FOIAed.

The entire section is worth reading — buy the book — for the way it lays out aspects of Barr’s corrupt actions that haven’t gotten as much focus as his intervention in the Roger Stone and Mike Flynn prosecutions.

The one piece of news Berman discloses is that the FBI was withholding the 302s from the intake of Rudy’s Russian disinformation from NY’s Assistant Director, William Sweeney.

There were FBI reports of those meetings, called 302s, which we wanted to review. So did Sweeney. Sweeney’s team asked the agents in Pittsburgh for a copy and was refused. Sweeney called me up, livid.

“Geoff, in all my years with the FBI I have never been refused a 302,” he said. “This is a total violation of protocol.”

This detail is worth considering given the still ongoing GOP witch hunt targeting recently retied FBI Senior Analyst Timothy Thibault because of the compartmented way this information was all treated.

[I]t has been alleged that in September 2020, investigators from the same FBI HQ team were in communication with FBI agents responsible for the Hunter Biden information targeted by [Brian] Auten’s assessment. The FBI HQ team’s investigators placed their findings with respect to whether reporting was disinformation in a restricted access sub-file reviewable only by the particular agents responsible for uncovering the specific information. This is problematic because it does not allow for proper oversight and opens the door to improper influence.

Third, in October 2020, an avenue of additional derogatory Hunter Biden reporting was ordered closed at the direction of ASAC Thibault. My office has been made aware that FBI agents responsible for this information were interviewed by the FBI HQ team in furtherance of Auten’s assessment. It’s been alleged that the FBI HQ team suggested to the FBI agents that the information was at risk of disinformation; however, according to allegations, all of the reporting was either verified or verifiable via criminal search warrants. In addition, ASAC Thibault allegedly ordered the matter closed without providing a valid reason as required by FBI guidelines. Despite the matter being closed in such a way that the investigative avenue might be opened later, it’s alleged that FBI officials, including ASAC Thibault, subsequently attempted to improperly mark the matter in FBI systems so that it could not be opened in the future.

Chuck Grassley is focusing on later compartmentalization of this investigation, when the origin of that compartmentalization stemmed from Barr’s efforts to limit the tentacles of the SDNY investigation. Instead of reviewing what Barr did, he is hounding one of the last remaining people at FBI who had investigated Trump’s Russian ties, with Chris Wray doing nothing to support the Bureau.

All the more so given that, both the end of this section — which is followed by a section in which Berman describes how the Parnas case ended up with one 2021 jury verdict and one 2022 guilty plea — and at the end of the entire chapter, Berman emphasizes that Barr’s tampering in the Rudy case was exceptional, even amidst all the other tampering he engaged in (to include interference in the Michael Cohen, John Kerry, Halkbank, and Cy Vance cases).

The episode was one of the crazier things I encountered over the whole course of my tenure, which is really saying something.

[snip]

The “intake process in the field” nonsense was clearly not driven by his sense that all that Ukraine material would be too much for the Southern District to handle. The only burden we needed lifted from us was the attorney general’s improper meddling.

And, when Berman describes what must include this investigation among the list of reasons why Barr fired him in June 2020, he includes it under an oblique reference to “prosecutions and ongoing investigations of those in his inner circle.”

I never speculated about the specific reasons Barr wanted me out. As an attorney, I avoid allegations that I do not yet have the facts to support. But it was no secret to me that much of what we did at the Southern District—and did not do—displeased Trump. And if it displeased the president, it would have displeased Barr. That’s how it worked.

From the Greg Craig case through the non-prosecution of John Kerry and on up to the prosecutions and ongoing investigations of those in his inner circle, it was clear to Trump that he could not control SDNY. We were not loyal to him; our fealty was to the mission.

At the time I was fired in mid-June 2020, the presidential election was less than five months away. I’m sure that Barr was tired of the Southern District’s independence. But it is also fair to assume there was a political component in his move to oust me.

Barr did the president’s bidding, no matter how he may try to deny that now. He no doubt believed that by removing me he could eliminate a threat to Trump’s reelection. [my emphasis]

I think there’s a good deal of evidence that Barr was not just trying to remove any threat to Trump’s reelection. He was trying to ensure that any investigations into Trump and his flunkies could not continue if and when Trump lost. In this period Barr not only closed, but disclosed the closure, of investigations into Paul Manafort’s slush funds, a suspected $10 million donation funneled through an Egyptian bank that had kept Trump afloat in September 2016, and probably parts of an investigation into Erik Prince. He replaced Donoghue in EDNY at a time when Tom Barrack was close to being charged (in the since failed prosecution). I’ve raised questions about how it became possible to disclose, literally the day before the 2020 election, the once ongoing investigation into whether Roger Stone conspired with Russia on a hack-and-leak campaign — one that may have involved “solid guy” Scott Brady. During this same period, another hand-picked US Attorney was literally presenting altered documents in the Mike Flynn docket in an attempt to blow up that prosecution (which had the side of effect of making any obstruction charges against Trump post-Presidency untenable); by September, one of those altered documents would serve as a prop in an attack Trump launched on Biden in the first debate.

Berman describes a lot of Barr’s related interventions that happened earlier — what he calls a “hostile takeover” of the DC US Attorney’s Office. But he doesn’t describe the rest of Barr’s tampering. And that tampering, which had more permanent effect, would have extended to SDNY’s investigation had Berman not dug in when Barr first tried to fire him.

Still, I find it interesting that Berman, the guy who saw how Barr prevented his office from receiving copies of the garbage that Rudy Giuliani brought home from Ukraine, describes it instead in terms of removing all threats to Trump’s reelection. As noted above, the part of the investigation that Barr assigned to EDNY rather than SDNY reportedly pertains at least in part to suspected Russian agent Andrii Derkach’s efforts to help Rudy obtain dirt on Hunter Biden, dirt that looks remarkably like the “Hunter Biden” “laptop,” dirt which Rudy brought to “solid guy” Scott Brady rather than SDNY. If Berman believes that an SDNY investigation into those matters, consolidated into one investigation, would have threatened Trump’s reelection chances, it suggests any scrutiny on Rudy’s effort to get dirt on Hunter Biden — the kind of dirt he eventually released!! — would have sunk Trump.

Instead, the circumscribed investigation that Berman managed to protect ended without charges.

As James Comer and Kevin McCarthy prioritize their investigation into Hunter Biden’s dick pics, Democrats might do well to investigate the full effect of Barr’s efforts to dismantle the investigation into Rudy’s meetings with Russian agents to obtain dirt that Trump could use in his reelection bid. Some of the same witnesses, including computer repairman Mac Issac, Rudy lawyer Robert Costello, and Rudy himself would be pertinent to both investigations.

All that’s the story included in the book, proper.

But Berman included an epilogue, perhaps a narrative feature dictated by publishing schedule or a desire to change the emphasis. In it, he describes an exchange that took place around March 9, 2020, during a period when “solid guy” Scott Brady was actively processing dirt that Rudy had obtained from suspected Russian agent Andrii Derkach. Berman describes that between the time Barr spun out the investigation into Rudy and the time when Barr fired Berman in hopes of protecting Trump’s reelection, he answered a question about the Parnas investigation in such a way that implied Barr had interfered in the Parnas investigation for political reasons.

In March 2020, I was asked if Bill Barr had interfered in our Lev and Igor prosecution. The question came to me during a press conference on an unrelated case, having to do with illicit doping of Thoroughbred horses.

“The Southern District of New York has a long history of integrity and pursuing cases and declining to pursue cases based only on the facts and the law and the equities, without regard to partisan political concerns,” I replied. “My primary commitment is and has been to maintain those core values and that’s how our office is operating.”

This was my only public statement as US attorney about the office’s political independence, and it was mild. But I did not answer that Barr never interfered for partisan reasons, because that would not have been true. That might have earned me another demerit. I was fired a few months later.

Though as Berman described it in the book, it wasn’t the Parnas investigation that Barr was interested in. It wasn’t even Rudy. It was the “tentacles” that had the “potential to spiral.”

To be clear, by March 2020, according to the book, Barr had interfered politically in several other ways — John Kerry, Greg Craig, Michael Cohen, Turkey, and others. This is not a comment limited to Rudy’s grifters.

But Berman chose to cap his book — which, as mentioned, focuses significantly on Berman’s success on unrelated cases, including things like the Epstein case — with something that occurred in March 2020, chronologically while Barr’s efforts to prevent the Rudy investigation from spiraling out of control were ongoing. That changes the lesson of Berman’s book, then, to a focus on Barr’s political interference.

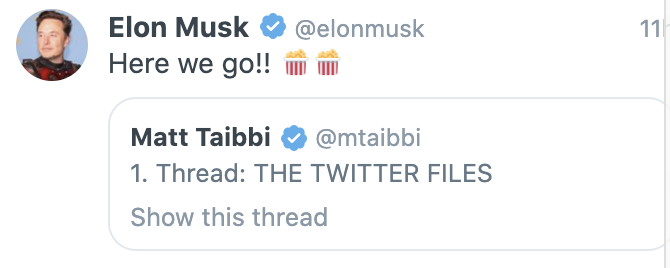

Just months ago, the US Attorney for SDNY published a book that laid out in detail how Trump’s corrupt Attorney General intervened to prevent the tentacles of a Hunter Biden adjacent investigation from spiraling out of his own control. And yet that has all been lost amid the din of outrage that Twitter took down Hunter Biden’s non-consensual dick pics.

Full transparency: On Twitter (they’re not coming up on a search of the Elmo-degraded site), I’m sure I also made comments about career people at DOJ preferring Barr to BDTS. I did so even while writing posts — one, two, three, four — that noted his role in Iran-Contra and the specious claims he had already made about the Mueller investigation.