We’ve gotten to that stage of another Durham prosecution where each new filing reads like the ramblings of a teenager contemplating philosophy after eating hallucinogenic mushrooms for the first time. This time it’s a reply filing in a motion in limine written by Michael Keilty (who I used to think was the adult in this bunch).

Before I show what I mean, I’m going to just share without comment my favorite part of the filing, where someone claims in all seriousness that hotel staffers — in a foreign country!! — don’t gossip about the kink of famous people.

It strains credulity, however, to believe that Ritz Carlton managers – with no apparent relationship to the defendant – would confirm lurid sexual allegations about a U.S. presidential candidate to a guest, let alone a stranger off the street.

Well, okay, I’ll make one comment. This is a gross misrepresentation of what Danchenko said, which is that the hotel staffers did not deny the rumor, not that they had confirmed them.

That done, I’m going to jump to the end, to where Keilty argues Durham should be able to present the allegation that led to the predication of a counterintelligence investigation against Danchenko in 2009 as well as the reason it was closed (because the FBI incorrectly believed Danchenko had left the US). Durham should be able to do that, the filing argues, so that the jury can contemplate the FBI’s obligation to consider whether they’re being played by foreign spies. [All the bold and underlining in this post are mine; the italics are Durham’s.]

The defendant asks the Court to limit the admissibility of evidence concerning the FBI’s prior counterintelligence investigation of the defendant to only the fact that there was an investigation. Limiting the evidence in this manner would improperly give the jury the false impression that the investigation closed due to a lack of evidence against the defendant. As discussed in its moving papers, the Government believes the facts underlying the investigation are admissible as direct evidence because in any investigation of potential collusion between the Russian Government and a political campaign, it is appropriate and necessary for the FBI to consider whether information it receives via foreign nationals may be a product of Russian intelligence efforts or disinformation. And in doing so, the FBI must consider the actual facts of the prior investigation. Had the FBI known at the time of his 2017 interviews that the defendant was providing them with false information about the sourcing of his claims, this naturally would have (or should have) caused investigators to revisit the prior counterintelligence investigation and raise the prospect of revisiting prior conduct by the defendant, including his statements to a Brookings Institute colleague regarding receipt of classified information in exchange for money and his prior contact with suspected intelligence officers. Whether or not the defendant did or did not carry out work on behalf of Russian intelligence, these specific facts are something that any investigator would or should consider and, therefore, the jury is entitled to learn at trial about the facts of the prior investigation in assessing the materiality of the defendant’s alleged false statements. The defendant should not be permitted to introduce the existence of the counterintelligence investigation for his benefit while suppressing the details of his conduct at issue in that very investigation.

This largely repeats the argument Keilty made in his original motion, before Danchenko responded, “Bring it!” to this request. I’ve underlined the language that appears exactly the same in both.

The Government anticipates that a potential defense strategy at trial will be to argue that the defendant’s alleged lies about the sourcing of the Steele Reports were not material because they had no affect on, and could not have affected, the course of the FBI’s investigations concerning potential coordination or conspiracy between the Trump campaign and the Russian Government. Thus, the Government should be able to introduce evidence of this prior counterintelligence investigation (and that facts underlying that investigation) as direct evidence of the materiality of the defendant’s false statements. Such evidence is admissible because in any investigation of potential collusion between the Russian Government and a political campaign, it is appropriate and necessary for the FBI to consider whether information it receives via foreign nationals may be a product of Russian intelligence efforts or disinformation. Had the FBI known at the time of his 2017 interviews that the defendant was providing them with false information about the sourcing of his claims, this naturally would have (or should have) caused investigators to revisit the prior counterintelligence investigation and raise the prospect that the defendant might have in fact been under the control or guidance of the Russian intelligence services. Whether or not the defendant did or did not carry out work on behalf of Russian intelligence, the mere possibility that he might have such ties is something that any investigator would consider and, therefore, the jury is entitled to learn at trial about the prior investigation in assessing the materiality of the defendant’s alleged false statements.

As noted, Danchenko responded to this request by stating that he planned to elicit the fact of the investigation himself.

The government seeks to admit evidence, in its case-in-chief or to rebut a potential defense strategy, that Mr. Danchenko was previously the subject of an FBI counterintelligence investigation over 10 years ago. On this point, Mr. Danchenko generally agrees that the proffered evidence is admissible but likely disagrees about the extent of evidence that should be admitted at trial. It is not disputed that Mr. Danchenko was the subject of a counterintelligence investigation. Nor is it in dispute that the counterintelligence investigation was closed in 2011. Likewise, it will not be in dispute that the FBI agents involved in the Crossfire Hurricane investigation were well aware of the prior counterintelligence investigation, that it was factored into their evaluation of Mr. Danchenko’s credibility and trustworthiness, that an independent confidential source review committee accounted for the prior investigation when recommending the continued use of Mr. Danchenko as a confidential human source through December 2020, and that the agents involved in the prior investigation were consulted and ultimately raised no objections, at the time, to Mr. Danchenko’s continued use as a source.

As an initial matter, those facts obliterate the government’s argument that any alleged false statements were material to the government’s ability to evaluate whether Mr. Danchenko could have been working for the Russians all along. It would be one thing to argue that the Crossfire Hurricane investigators were not aware of the prior investigation and Mr. Danchenko failed to inform them of it when asked. But, as one might expect, Mr. Danchenko was not aware of the investigation. He learned of it when then Attorney General William Barr made public a summary of that investigation on September 24, 2020. Moreover, it stretches credibility to suggest that anything else would have caused the FBI to be more suspicious of Mr. Danchenko’s statements and his potential role in spreading disinformation than the very fact that he was previously investigated for possibly engaging in espionage on behalf of Russia. Armed with that knowledge, however, and based on the substantial and “critical” information Mr. Danchenko provided to the FBI throughout his time as a source, the FBI nevertheless persisted. The Special Counsel perhaps disagrees with that decision, but Mr. Danchenko’s trial on five specific statements and this is not the place to air out the Special Counsel’s dissatisfaction.

Mr. Danchenko himself intends to elicit from government witnesses their general knowledge of Mr. Danchenko’s prior investigation. But the details of that investigation are not relevant and, more importantly, are unproven, would involve multiple levels of hearsay to establish the basis for the investigation let alone prove the allegation, and resulted in no negative action or conclusion. Indeed, the investigation was closed and to undersigned counsel’s knowledge never reopened even after the Special Counsel’s investigation and Indictment. Contrary to the Special Counsel’s insinuations and allegations, we expect the jury will hear that Mr. Danchenko was a vital source of information to the U.S. government during the course of his cooperation and was relied upon to build other cases and open other investigations. [my emphasis]

Curiously, this dispute is taking place without discussion of how Durham intends to introduce this information, other than precisely the way Danchenko proposes to: by asking the Crossfire Hurricane witnesses what they knew about it, which would lead them to explain that they knew about the prior investigation and took it into account, which would be the relevant issue as far as materiality.

Given Danchenko’s suggestion (bolded above) that the counterintelligence agents from 2011 didn’t complain that Danchenko was used as a source “at the time,” I wonder whether they’ve since decided (or been coerced, as Durham has done with so many of his witnesses) that they now think it’s relevant. That might explain why Danchenko was discontinued as a source, too: Imagine if, after Billy Barr violated DOJ guidelines by making this public in 2020, the original agents were invited to complain in October 2020, which led to Danchenko’s discontinuation. Perhaps Durham wants to have those other agents testify as witnesses about what a sketchy man they believed Danchenko to be, over ten years ago, so sketchy that they lost track of him and concluded incorrectly he had left the country.

But having learned that Danchenko not only is willing but wants Crossfire Hurricane witnesses to explain how they took this earlier counterintelligence investigation into account, Durham has doubled down that that is not enough. It is not enough to hear how the FBI personnel who interviewed Danchenko took the earlier investigation into account, the jurors must learn the details of the earlier investigation so they can take it into account.

Granted, your average EDVA jury might have one or two people who have security clearances on it. But Durham is effectively asking untrained jurors to weigh decade-old uncharged and unproven counterintelligence allegations in their deliberation over whether answers Danchenko gave the FBI five years ago should have been viewed more skeptically by trained counterintelligence personnel. He’s doing so even though (and this a key point in Danchenko’s motion to dismiss, though that MTD is unlikely to work) the FBI took action based on Danchenko’s responses on these topics as if the answer was precisely what Durham says it should have been.

The FBI took Danchenko’s descriptions of Charles Dolan’s close ties to Russians like Dmitry Peskov and opened an investigation into him, just like Durham says would have happened if Danchenko had not (allegedly) hidden that Dolan provided him information that showed up in the dossier. The FBI took Danchenko’s descriptions of how sketchy the call he thought might have been with Sergei Millian and concluded from that that the report in the dossier wasn’t all that credible (though they didn’t incorporate that into their FISA applications), just like Durham says should have happened. And based, in part, on Danchenko’s description of his contributions to the dossier, the Mueller team made no further use of the dossier — not to predicate the investigation into Michael Cohen, not to continue the investigation into Paul Manafort (which was premised instead on his money laundering), not to direct the focus of the investigation, which instead looked at things like the June 9 Trump Tower meeting and Konstantin Kilimnik’s role, both of which would have been in the dossier if it were a credible product.

Durham is accusing Dancehnko of lying about two topics that the FBI nevertheless responded to (Page FISA aside) as if they took the answer to be precisely what Durham says it should have been.

He’s doing it in a filing where Durham can’t keep straight basic details of knowability and truth.

For example, in one place he accused Danchenko of telling the truth, just not the truth that Durham wishes he had told. He says it is proof that Danchenko lied that he truthfully answered Christopher Steele would know about Dolan because Danchenko cleared his October 2016 trip to Russia with Steele.

Second, when the defendant was asked “would Chris know of [Dolan]?” the defendant replied “I think he would . . . . because I cleared my [October] trip with Chris.” However, as discussed in the Government’s moving papers, the defendant (1) attempted to broker business between Steele and Dolan, (2) provided Dolan with a copy of his Orbis work product, and (3) apparently informed Dolan of Steele’s former employment with MI-6.

Two of Durham’s complaints — that Danchenko provided Dolan something from Orbis and that Danchenko informed Dolan that Steele worked for MI6 (I suspect Durham is wrongly attributing this to Danchenko but let’s run with it) — have nothing to do with what Steele would know, and so would be non-responsive to the FBI question. They have to do with what Dolan would know, not what Steele would know (even there, as I have noted, the uncharged question Danchenko was asked and his response were not what Durham claims it was).

Durham similarly complains that Danchenko didn’t tell the FBI something he didn’t know but that they did: the extent of communications between Dolan and Olga Galkina.

Third, while the defendant did introduce Dolan to Ms. Galkina, the Government anticipates introducing evidence through the defendant’s handling agent that the defendant was unaware of the extent of communication between Dolan and Galkina. This is a highly material fact given that both Dolan and Galkina are alleged to have been sources for the Steele Reports.

Durham may mean to suggest that if only Danchenko had … I’m not even sure what, the FBI would have discovered the communications that he describes here and wants to present at trial that the FBI discovered. Except as I noted last year, the reason the FBI started asking about Dolan is because they targeted Olga Galkina with a 702 directive that disclosed the contacts she had with Dolan. The FBI came into the interview in question knowing what Danchenko didn’t know and nevertheless Danchenko didn’t hide what he did know. What Danchenko did not know but the FBI did is proof, Durham says, that Danchenko lied.

Perhaps the craziest claimed proof that Danchenko is lying in this filing is where Durham complains that Danchenko didn’t offer up something that his own witness, Dolan, still won’t testify to.

According to the indictment, Danchenko both visited Dolan at the Ritz on June 14, 2016 and posted a picture of the two of them in Red Square (remember, he’s claiming Danchenko was hiding this stuff — the stuff he posted on social media).

On or about June 14, 2016, DANCHENKO visited PR Executive-1 and others at the Moscow Hotel, and posted a picture on social media of himself and PR Executive-1 with Red Square appearing in the background.

He complains that when Danchenko was specifically asked if Dolan could be a source for Steele (Durham has persistently misrepresented the nature of this question), he did mention they were in Moscow together in fall 2016, but didn’t mention June 2016.

In the January 2017 interviews, the defendant never mentioned Charles Dolan. Further, during the defendant’s June 2017 interview with the FBI (which forms the basis of the false statement charge related to Dolan), the defendant only informed the FBI that he was present with Dolan during the October 2016 YPO conference. Again, the defendant conveniently whitewashed Dolan from the June 2016 planning trip in Moscow.

[snip]

First, as discussed above, the defendant did not inform the FBI that Dolan was present at the Ritz Carlton in June 2016. Again, this is a material omission because the defendant informed the FBI that he collected information for the Steele Reports in June 2016, but not during the October 2016 trip. Dolan’s proximity to the defendant during this time period is a highly relevant fact.

Durham wants to prove that Danchenko told an affirmative lie in June 2017 by denying that he had spoken to Dolan about topics that showed up in the dossier (in reality, Danchenko told the FBI, “We talked about, you know, related issues perhaps but no, no, no, nothing specific”). And to support that claim, he offers as proof that Danchenko offered up true information but not the information that Durham himself would have wanted him to offer up. Again, he’s arguing that Danchenko lied by pointing to his true statements.

And he’s making that argument even though his primary witness to all this — Dolan — apparently continues to testify that he does not remember meeting Danchenko at the Ritz.

[T]he Government anticipates that Dolan will testify that he has no recollection of seeing the defendant at the Ritz Carlton in June 2016.

Durham will prove that Igor Danchenko lied, he says, because along with offering true information, he didn’t offer up something that his star witness still won’t testify to remembering.

Let’s go back, shall we, to where we started: The urgency of letting EDVA jurors consider whether FBI’s counterintelligence personnel weighed Igor Danchenko’s past counterintelligence investigation adequately before they decided he was credible and took exactly the actions they would have taken if Danchenko had testified the way Durham claims he falsely did not.

It has been clear from the start that they did take the past CI investigation into account. Indeed, when his interview transcript was first made public, I observed that Danchenko’s interviewers were most skeptical of his evasions about ties to Russian spies. And Danchenko reveals that “an independent confidential source review committee” gave that earlier investigation particular focus when they did a source review of Danchenko’s reporting.

The Crossfire Hurricane team considered it and found Danchenko reliable. The confidential source review committee considered it and found Danchenko reliable. But Durham knows better, and he’s betting that an untrained EDVA jury will agree with him on that point.

But it’s not just Danchenko’s credibility that is at issue. As I previously noted, one reason Durham wants to get into the nitty gritty details of the predication of the investigation against Danchenko is because he expects Danchenko will look at the investigations of others on whom Durham is relying as sources.

[T]he Government expects the defense to introduce evidence of FBI investigations into other individuals who the Government anticipates will feature prominently at trial. Thus, the introduction of the defendant’s prior counterintelligence investigation – should the defense open the door – does not give rise to unfair prejudice that substantially outweighs its probative value.

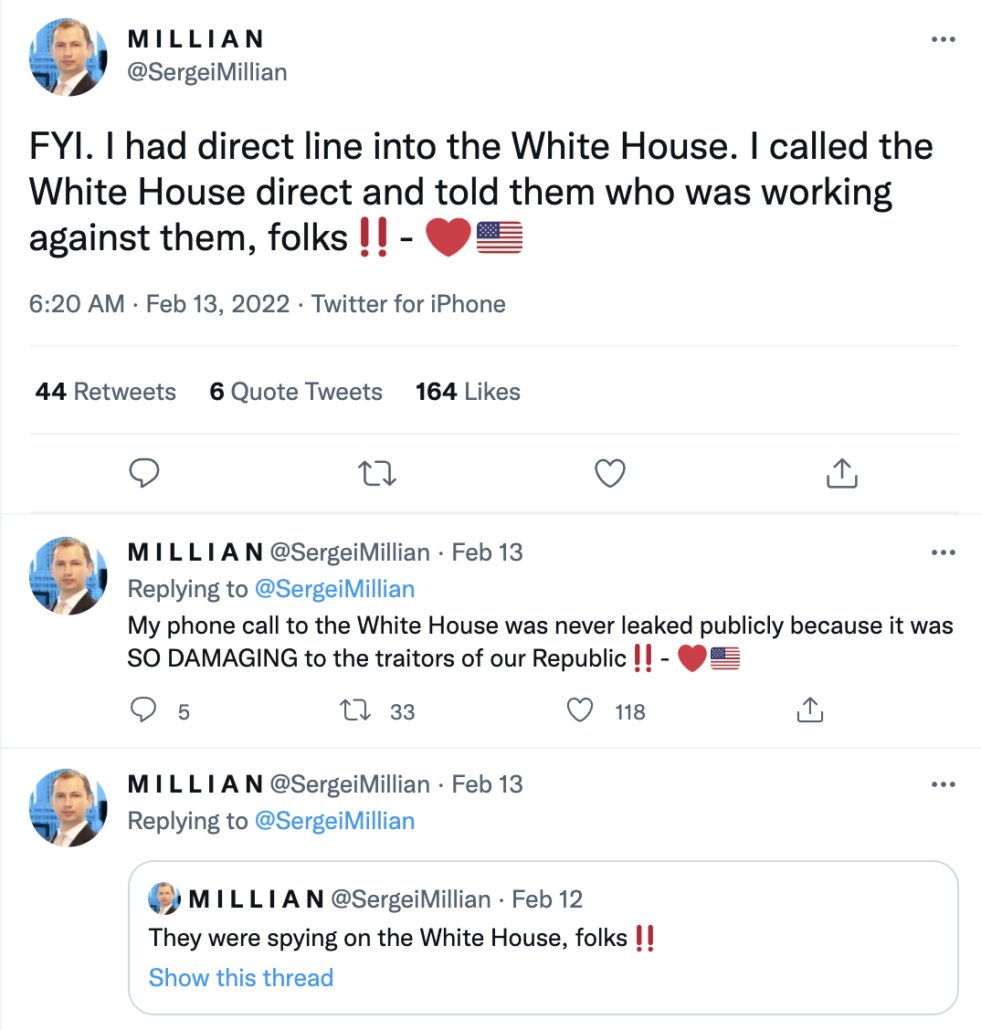

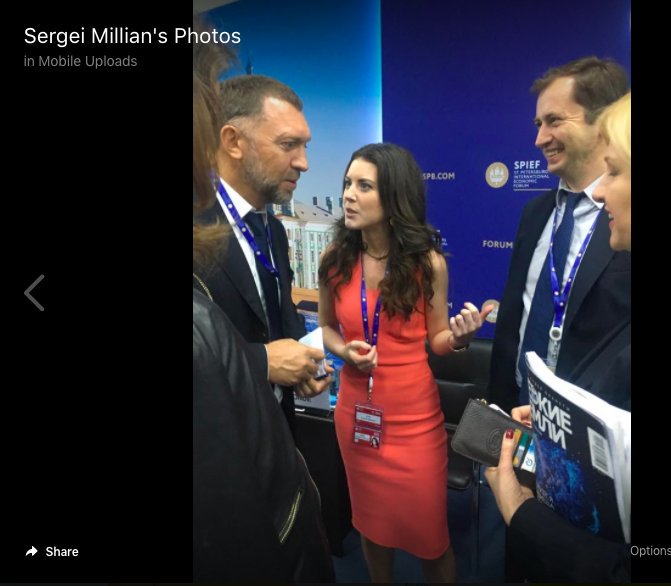

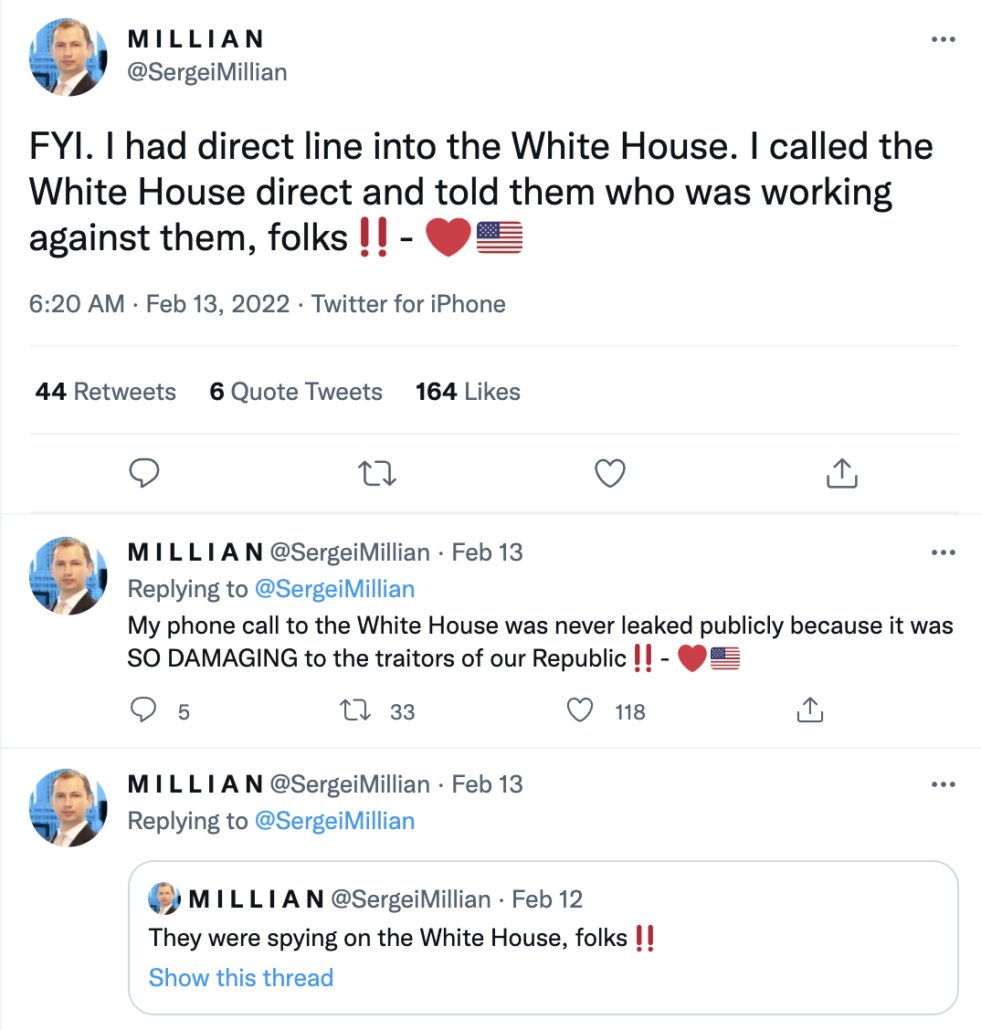

Durham wants to be able to talk about the earlier counterintelligence investigation that the Crossfire Hurricane team did consider, because Danchenko is likely to raise the counterintelligence investigation into Sergei Millian and Dolan and probably some other people too. There’s no evidence Durham considered those counterintelligence investigations before building elaborate conspiracy theories based on the claims of those witnesses.

Durham said that in the same section where he also said,

[T]n any investigation of potential collusion between the Russian Government and a political campaign, it is appropriate and necessary for the FBI to consider whether information it receives via foreign nationals may be a product of Russian intelligence efforts or disinformation.

That is, shortly before Durham said that he has to talk about the predication of the counterintelligence investigation into Danchenko to even things out if he decides to raise the counterintelligence investigations into Millian, Dolan, and who knows who else, Durham said it is necessary to consider whether someone is being played by Russian intelligence.

In fact, he originally made this claim in a long filing in which he laid out how he had had his ass handed to him by Sergei Millian (though he didn’t confess how badly Millian had played him).

Before Durham charged Danchenko, he had not obtained the evidence from the DOJ IG investigation; he shows no familiarity with either the Mueller Report or the Senate Intelligence Committee Report. He never once made Millian substantiate his claims in an interview in which he could be held accountable for false claims. And he never once interviewed George Papadopoulos to learn how Millian was cultivating him during precisely the period that Durham is sure he didn’t call Danchenko. But he wants a jury to decide that the Crossfire Hurricane team didn’t consider the reliability of someone about whom the FBI has opened a counterintelligence investigation.

Durham charged two men as part of a larger uncharged conspiracy theory that the Hillary campaign “colluded” [sic] with Russia to say bad things about Donald Trump. And yet he never “consider[ed] whether information” he received from Millian and others “may be a product of Russian intelligence efforts or disinformation.”

And because he charged this case without considering that, Durham is demanding that he get to present why the FBI opened a counterintelligence investigation against Danchenko 13 years ago.