Ted Yoho Says Lynching Is Not A Hate Crime

Yesterday, in an historic vote by the overwhelming total of 410 to 4, the US House of Representatives passed HR 35, the Emmitt Till Antilynching Act. Here is how the Washington Post described the efforts leading to the bill, which took over 100 years to pass:

The House on Wednesday overwhelmingly passed legislation that would make lynching a federal hate crime, more than 100 years since the first such measure was introduced in Congress.

H.R. 35, the Emmett Till Antilynching Act, was approved on a bipartisan 410-to-4 vote after a sometimes emotional debate in the House. Rep. Bobby L. Rush (D-Ill.), who sponsored the legislation, said the bill will “send a strong message that violence, and race-based violence in particular, has no place in American society.”

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) also took to the floor to salute Rush for spearheading the bill and to urge members to support it.

“We cannot deny that racism, bigotry and hate still exist in America,” she said, citing the 2017 white nationalist rally in Charlottesville, among other recent incidents.

The measure’s passage comes after lawmakers tried, and failed, to pass anti-lynching bills nearly 200 times.

So, who could possibly be against the idea of lynching being a hate crime? One of them turned out to be the Congressman from my district, Republican Ted Yoho. In an interesting coincidence, another is the Congressman from Marcy’s district, Independent Justin Amash. Yoho and Amash differ by the caucuses to which they belong. Yoho, along with fellow No-voter Louie Gohmert of Texas, belongs to the Freedom Caucus, which routinely supports the most extreme right-wing conservative Republican policies, especially those that repress any citizens besides old white males. Amash, on the other hand, along with fellow No-voter Thomas Massie of Kentucky, caucuses with fellow Libertarians. One might try to say that at least the Libertarians are trying to make the point that we don’t need an extra law to declare lynching a hate crime because killing is already a crime. I would counter that lynching occupies a position of huge significance in the history of our country and that its especially heinous nature, coupled with the intent to inflict terror on all people of color, makes it the ultimate hate crime and worthy of distinction even if no other crime rose to the level of a hate crime. For the Freedom Caucus members, it’s much easier to see how they get there. They are straight up racist in the bulk of their policies and they support a president who praised violent white nationalists who killed a protester in Charlottesville.

I’ll leave it to Marcy to go further into what may have led Amash to such a despicable position on this bill. The rest of this post will be aimed at describing and placing into context the severe harm that Yoho has done with this vote.

As a scientist, a horse owner and neighbor living just a few blocks away, I have struggled since his election to try to find some way to like Ted Yoho or to at least find a reason to admire him on even one front. After all, before he ran for office, he treated one of our horses once when he was the weekend area horse vet on call and one of our horses had a problem. Sadly, even though I know for a fact that he is a competent vet with the commensurate professional training and compassion for animals, his behavior in Congress has been to throw in with the extremely low-brow, anti-intellectual hate mongering that characterizes Trump’s Republican Party. Then, when he announced recently that he would not seek reelection this year, I had new hope that he would stop role-playing to get election funds and vote his conscience. That hope got dashed when Yoho continued boorish Freedom Caucus behavior and voted against both Trump articles of impeachment. Yesterday’s vote, then, leaves me unable to draw any other conclusion than that Yoho actually believes the racist tripe that the Freedom Caucus spouts if he’s willing to team up with fellow retiring dead-ender Gohmert to cast such a hate-filled vote.

But it gets much worse. As a resident of Alachua County, it seems impossible that Yoho would not know that our county has embarked on a Peace and Reconciliation Plan aimed at confronting the history of racial violence and lynching in our county. In November of 2018, a busload of Alachua County residents went to Montgomery, Alabama to visit the National Memorial for Peace and Justice. Here is part of the description of that trip:

As part of a trip to Montgomery, Alabama, last month, members of our community visited the Legacy Museum, which explores the aftermath of slavery, lynching, Jim Crow laws and their link to mass incarceration in U.S. history. We met with officials from the Equal Justice Initiative, which administers the Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice about a mile away.

/snip/

Through the Equal Justice Initiative’s work, descendants of lynching victims and others collect soil from the crime scenes into containers labeled with their names. Dozens of glass jars filled with dirt and clay line museum shelves. The intention is to gather the dried blood and tears, the symbolic DNA of the victims, to take it to a place where it will be honored and memorialized, instead of leaving it at a forgotten parking lot, roadside or remote wooded area.

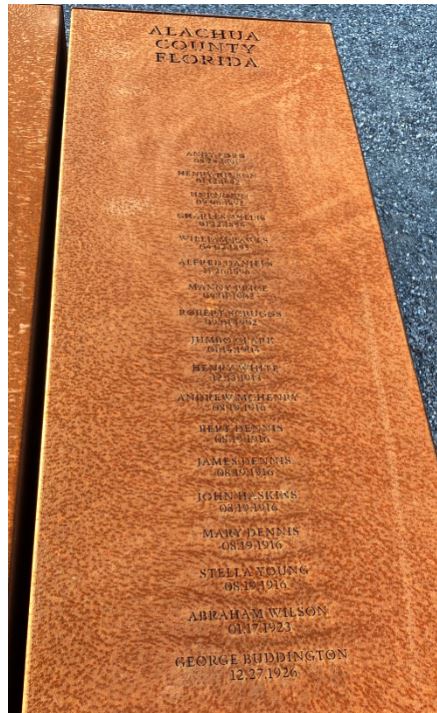

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice lists the names of more than 4,000 African American men, women and children lynched between 1877 and 1950 in 800 different counties across the country. The names are engraved on coffin-shaped metal slabs that stand or are suspended over the memorial space. From a distance, the rusting monuments in various shades of brown call to mind the bodies of these victims that haunt our history.

We read 18 names on the Alachua County slab, although local researchers have already identified more than twice that number of actual victims. Remembering this cruelty and honoring the memories of its victims does not mean we are dwelling in the past. Naming them and our role in this terror is a step in the process of transcending the past and beginning to heal.

The idea is to go through a truth and reconciliation process, and for each county to claim a replica of their historical marker to take back to their own community. As part of Alachua County’s truth and reconciliation process, we need to take an honest look at the following: the history of the role of slavery in the creation of wealth in our county; the history of lynching and illegal corporal punishment; and documentation of disproportionate negative contact and prosecution of persons of color by law enforcement and the criminal justice system.

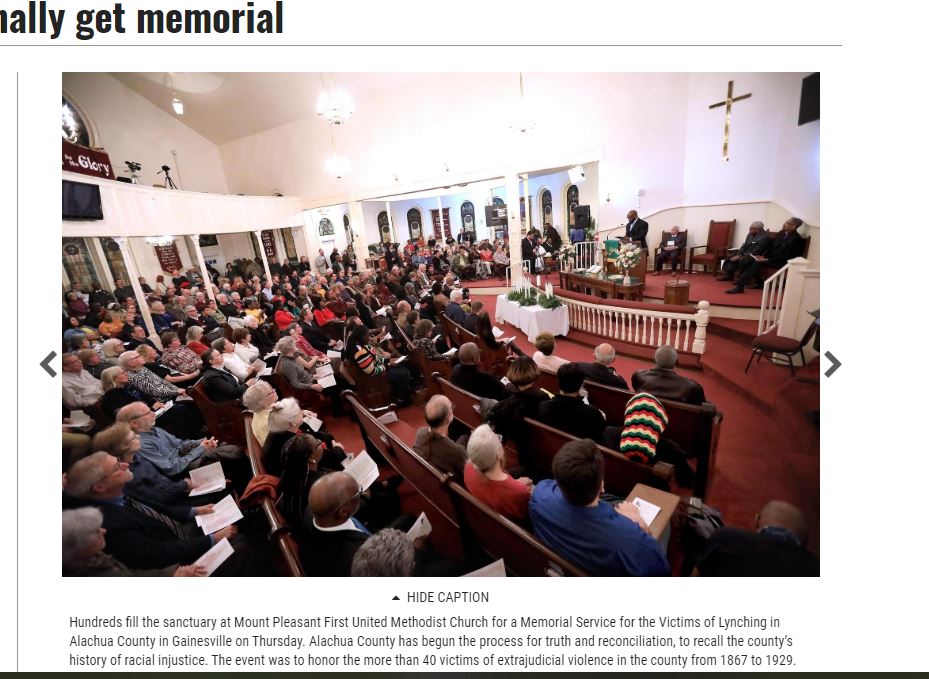

More recently, on February 7 of this year, there was a memorial service in Gainesville to recognize the victims of racial violence in our county and to continue the process aimed at a permanent memorial in their honor. Here’s a partial screencap of the Gainesville Sun article on the service, showing the crowd gathered for the service. I was able to attend this service and found it extremely powerful:

That service was followed by another bus trip, this time to both Selma and Montgomery, Alabama on February 13 to February 15. I was able to join this group, as well. The feature image for this post is a view from inside the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, looking toward the large structure housing the monuments for each county’s list of lynching victims. Here’s the Alachua County monument:

But what really seared into my memory were the multiple collections of jars of soil from lynching sites. Here’s my photo of one such wall in the building housing the meeting room and gift shop at the National Memorial:

This powerful video, recorded prior to the completion of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, includes Bryan Stevenson (yes, this is the same Bryan Stevenson you will recognize from the movie “Just Mercy”) describing the soil collection process and shows some collections as they occurred:

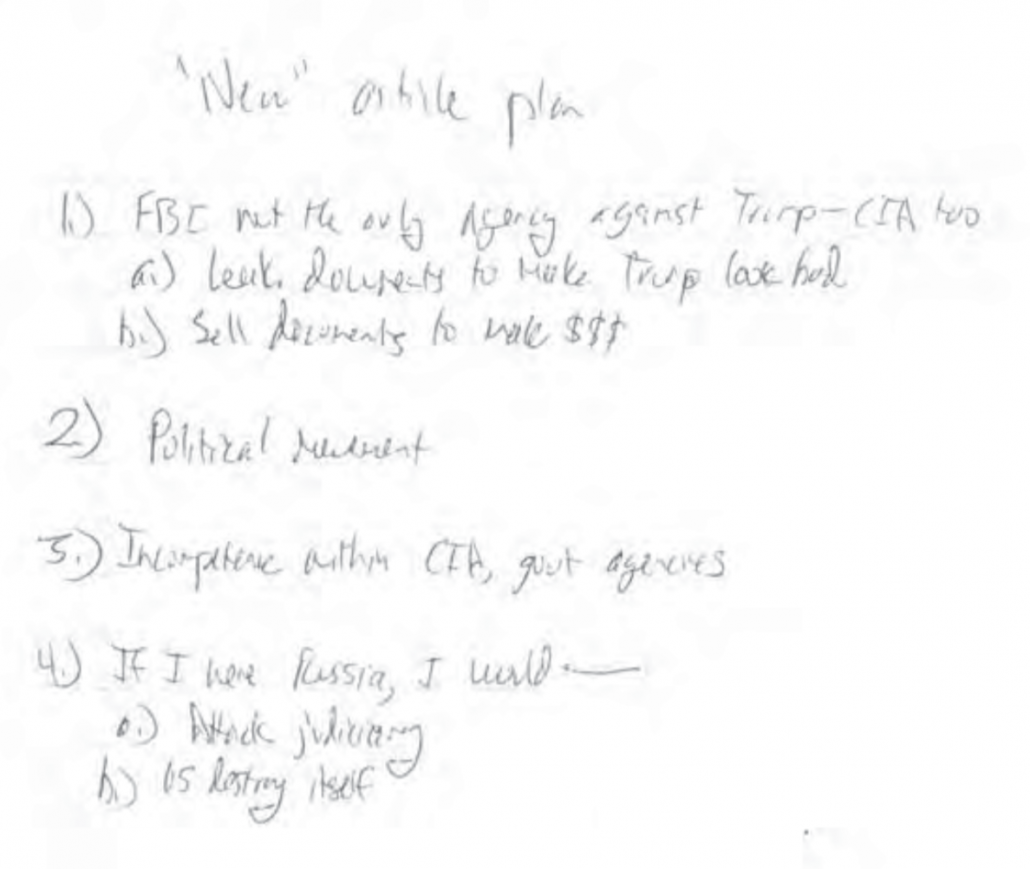

When our group gathered for an informational meeting prior to the trip, we each drew a name of a victim of racial violence in Alachua County to take with us on the trip. Here’s the name I got:

This name is not on the memorial in Montgomery, as only 18 are carved in now. After further research, there are now over 40 known vicitms in our county. It was moving to walk through these sites commemorating what has happened to people of color in our county out of fear, prejudice and hate while holding onto this name. Then, on Tuesday of this week, our group re-gathered to share a meal and to hold our own memorial service. As each victim’s name was read off the list, a candle was lit in their honor and the person who had carried the name stood in our circular gathering of chairs. Just typing this memory brought me to tears.

On April 4, our community will gather just west of Gainesville in the small town of Newberry, but still within Alachua County, to collect soil from a known lynching site. I will do my best to go to this, since Reverend Josh Baskin(s) was among the Newberry 6 lynched in August of 1916.

Now consider just how damaging Ted Yoho’s vote yesterday is. Our community has been coming together for years in a process meant to draw attention to, to commemorate and to honor the victims of racial violence in our county. In the midst of this process, Yoho just inserted a vile piece of racial hatred that reminds us that the road to peace and reconciliation will not be short. It has taken 100 years for these victims to be recognized and for Congress to pass legislation pointing out the level of hatred involved. Yoho’s vote reminds us that the first African-American US president has been followed by a president who thrives on stoking racism and hatred.

But we must not give in. This quote from Rep. John Lewis’s book “Across That Bridge: A Vision for Change and the Future of America” was reproduced in the booklet with our trip information (and I had highlighted it when I read the book just before leaving):

Take a long hard look down the road you will have to travel once you have made a commitment to work for change. Know that this transformation will not happen right away. Change often takes time. It rarely happens all at once…

Use the words of the movement to pace yourself. We used to say that ours is not the struggle of one day, one week, or one year. Ours is not the struggle of one judicial appointment or presidential term. Ours is the struggle of a lifetime, or maybe even many lifetimes, and each one of us in every generation must do our part. And if we believe in the change we seek, then it is easy to commit to doing all we can, because the responsibility is ours alone to build a better society and a more peaceful world.

There is so much comfort in these words from such a dedicated veteran of the movement. Sadly, Congressman Lewis was too ill to be present to cast a vote in favor of HR 35, but we can rest assured that he has voted in favor of every previous attempt to pass such a bill during his tenure in Congress.

To Ted Yoho, all we need to say is that your time for promoting hate in the US Congress is coming to an end at the end of this year. Your views will eventually lose out, and peace and justice will eventually come to our country. There are simply more people who are working for peace and justice than there are promoting hate. Even within our current Congress, which has many Republicans who endorse the bulk of the racist Republican agenda, you were outvoted by over 100-1 on the issue of lynching being a hate crime. The Senate and House versions of this legislation will soon be synchronized, and even if your racist president chooses to veto, there are enough votes to override this last-ditch effort to spread hate.