The Money Trail Stuck in an Appendix of the January 6 Report

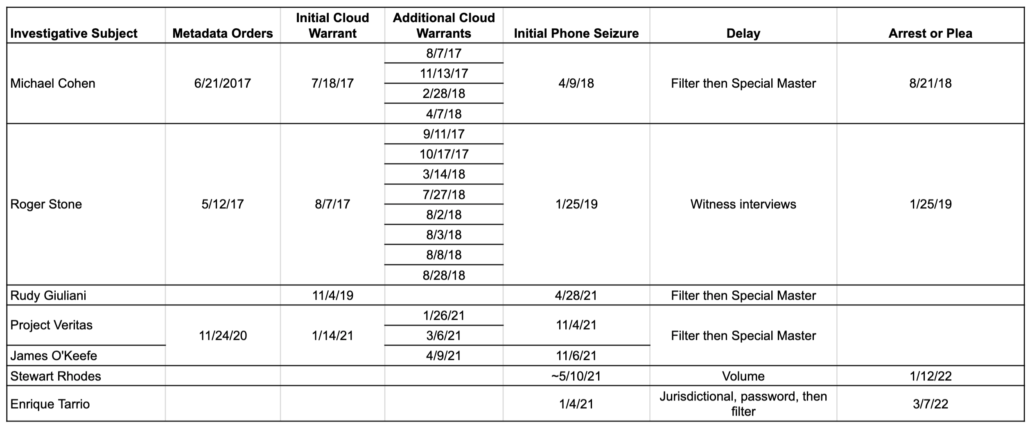

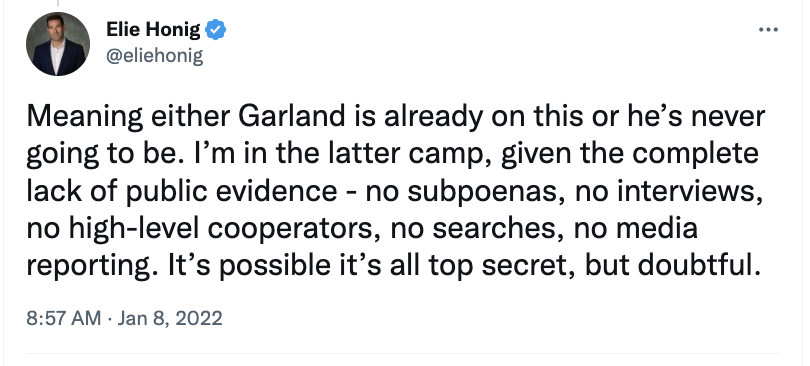

Several weeks before the January 6 Committee released its report, CNN published a somewhat overlooked report describing the investigation that Jack Smith has inherited. Among other things, it revealed that (as Merrick Garland had promised) DOJ was following the money.

Another top prosecutor, JP Cooney, the former head of public corruption in the DC US Attorney’s Office, is overseeing a significant financial probe that Smith will take on. The probe includes examining the possible misuse of political contributions, according to some of the sources. The DC US Attorney’s Office, before the special counsel’s arrival, had examined potential financial crimes related to the January 6 riot, including possible money laundering and the support of rioters’ hotel stays and bus trips to Washington ahead of January 6.

In recent months, however, the financial investigation has sought information about Trump’s post-election Save America PAC and other funding of people who assisted Trump, according to subpoenas viewed by CNN. The financial investigation picked up steam as DOJ investigators enlisted cooperators months after the 2021 riot, one of the sources said.

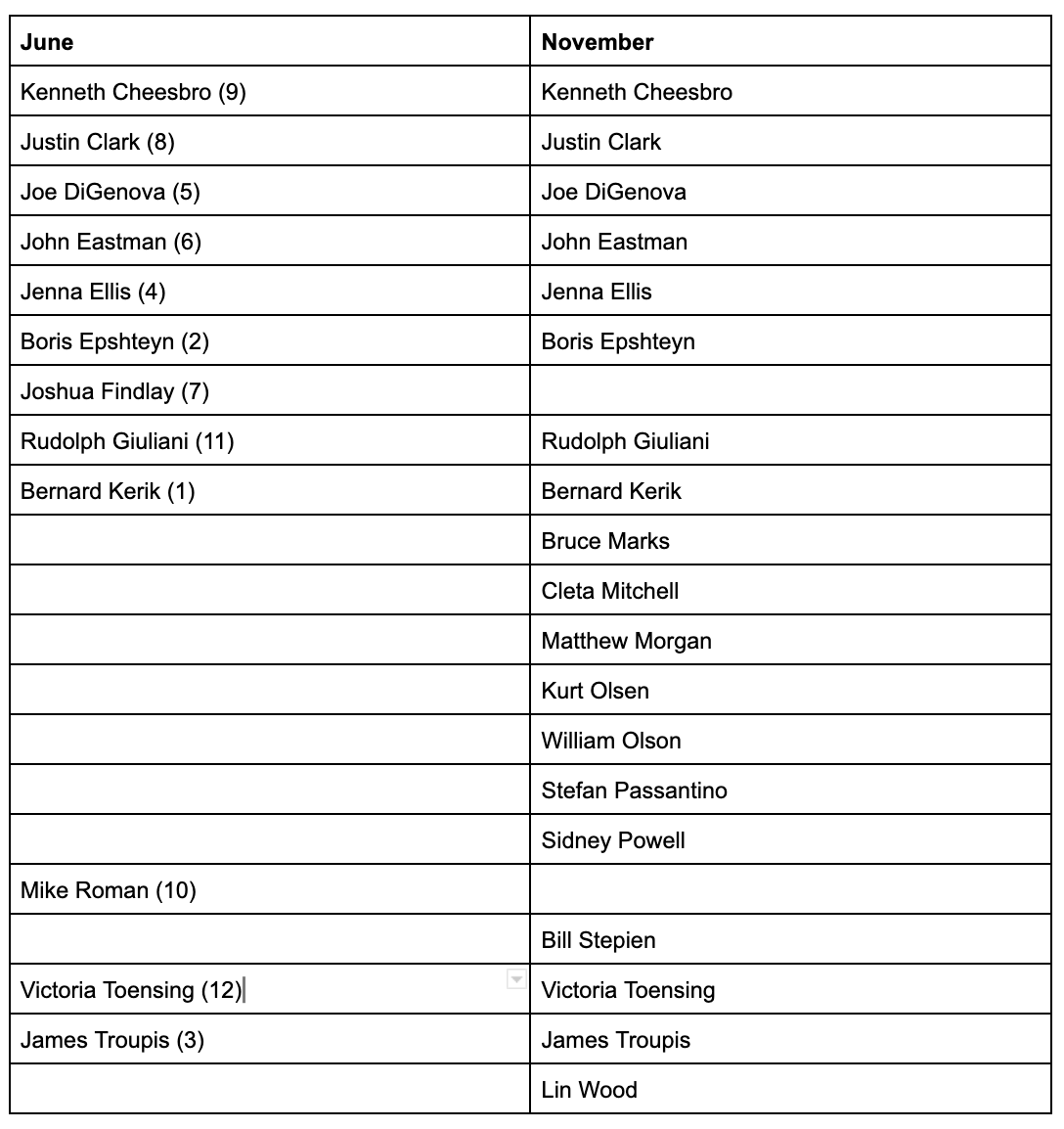

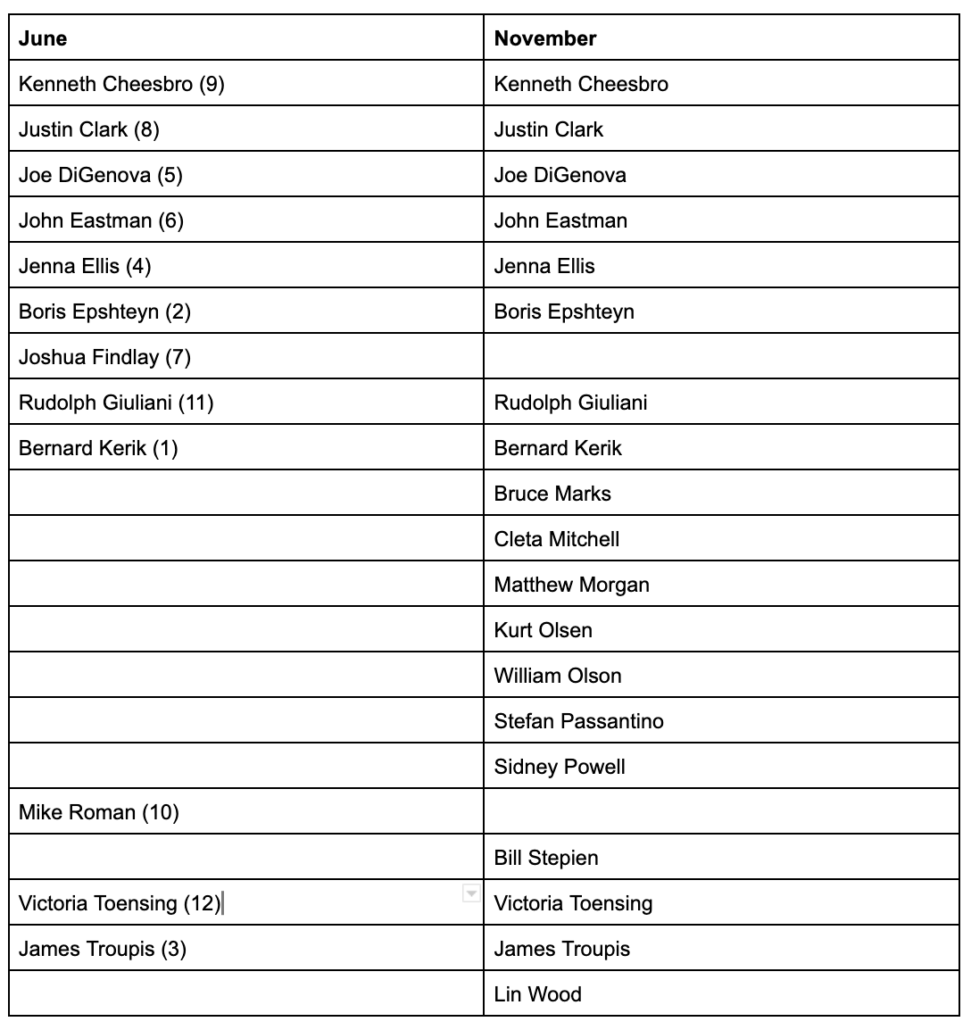

Given the report that DOJ already has a robust investigation into the money trail, was a bit surprised that the January 6 Committee not only didn’t refer Trump for financial crimes — an easier way to look smart than referring him for inciting insurrection when DOJ has charged no one with insurrection — but relegated the financial part of the report to an appendix. I thought that choice was especially odd given that the false claims Trump made about the Big Lie were repurposed in campaign ads. But among other things, because Alex Cannon (he of the good Maggie Haberman press on the stolen document case) happened to be assigned both to debunking claims of voter fraud generally and he was part of the ad approval process (but as someone who had been doing vendor relations for Trump golf courses until shortly before he moved to the campaign, he was totally unprepared to deal with campaign finance law), you have a witness otherwise exposed in DOJ investigations who recognized the fundraising claims could not be substantiated.

Q Okay. Did you have discussions with anyone within the campaign about the inflammatory tone of the post-election emails?

A Yeah. mean, I did mention it to Justin Clark.

Q What did you say to him?

A That, you know, I just didn’t love the messaging, something along those lines.

Q What was the issue you had with the messaging?

A I think it’s just some of it seemed a little over the top to me.

Q Because you had just spent weeks researching and looking and trying to figure out what was verifiable and what wasn’t right?

A Yes, maam.

Q You had had face-to-face conversations with Mark Meadows, with Peter Navarro, with the Vice President. You’d been told to your face you’d been accused of) being an agent of the deep state in response to telling people the truth about what you were seeing in terms of election fraud that was verifiable or would be admissible in court, hadn’t you?

A Yes

Q And, in response to all of the truth that you were propounding to people, you watched for weeks as the ton of these email got stronger and more inflammatory, raising millions — hundreds of million dollars off of theories that you had spent weeks debunking and denying because you had found that they were not verifiable, right?

A I can see how you would draw that conclusion.

As one of the J6C hearings had noted — and as the appendix lays out in more depth — Trump continued to fundraise until the riot kicked off on January 6.

Within the campaign, there was a really junior staffer who got fired, seemingly because he refused to make false claims in ads.

In that meeting, as Coby addressed the staff and expressed that the digital team would continue to work, Ethan Katz, an RNC staffer in his early twenties, rose to ask a question: 130 How were staffers supposed to tell voters that the Trump Campaign wanted to keep countingvotes in Arizona but stop counting votes in other States (like Pennsylvania, Georgia, and Michigan)? 131

Katz said that Coby provided an answer without substance, which caused Katz to reiterate his question. His question made clear that the Campaign’s position was wildly inconsistent.132 Allred and Boedigheimer corroborated that Katz confronted leadership.133

Katz also recalled that, shortly after the election, Allred directed him to write an email declaring that President Trump had won the State of Pennsylvania before anyone had called Pennsylvania for either party.134 Katz believed the Trump Campaign wanted to send this email out to preempt apotential call that was likely to be in former Vice President Biden’s favor.135 He refused to write the email. Allred was stunned, and instead assigned it toanother copywriter.136 Allred confirmed that Katz expressed discomfort at writing such an email and that she relied on another copywriter.137 On November 4, 2020, the Trump Campaign sent out an email preemptively and falsely declaring that President Trump won Pennsylvania.138 Katz was fired approximately three weeks after the election.139 In aninterview with the Select Committee, when Allred was asked why Katz, her direct report, was fired, she explained that she was not sure why because TMAGAC was raising more money than ever after the election, but that the decision was not hers to make.140

The RNC simply stopped echoing all the claims Trump was making.

Allred and Katz both received direction from the RNC’s lawyers shortly after the election to not say “steal the election” and instead were told to use “try to steal the election.”94 Allred also recalled that, at some point, theRNC legal team directed the copywriters not to use the term “rigged.”95

After the media called the election for former Vice President Joe Biden on Saturday, November 7, 2020, the RNC began to quietly pull back from definitive language about President Trump having won the election and instead used language of insinuation. For example, on November 10, 2020, Justin Reimer, RNC’s then-chief counsel, revised a fundraising email sent to the Approvals Group to remove the sentence that “Joe Biden should not wrongfully claim the office of the President.”96 Instead, Reimer indicated the email should read, “Joe Biden does not get to decide when this election ends. Only LEGAL ballots must be counted and verified.”97 Both Alex Cannon and Zach Parkinson signed off on Reimer’s edits.98

On November 11, 2020, Reimer again revised a fundraising email sent to the Approvals Group. This time, he revised a claim that “President Trump won this election by a lot” to instead state that “President Trump got 71 MILLION LEGAL votes.”99 Once again Cannon and Parkinson signed off on Reimer’s edits.100 Also on November 11, 2020, Jenna Kirsch, associate counsel at the RNC, revised a fundraising email sent to the Approvals Group to, among other things, remove the request “to step up and contribute to our critical Election Defense Fund so that we can DEFEND the Election and secure FOUR MORE YEARS.”101 Instead of “secure FOUR MORE YEARS,” Kirsch’s revised version stated a contribution would “finish the fight.”102 Once again Cannon and Parkinson signed off on these edits for the Trump Campaign.103 Regarding the change to finish the fight, Zambrano conceded, “I would say this a substantive change from the legal department.”104 Kirsch made numerous edits like this, in which she removed assertions about “four more years.”105 Such edits continued into late November 2020.

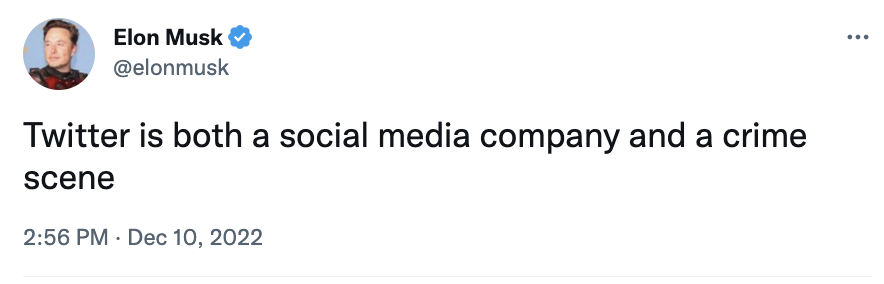

Even so, the fundraising emails from both the campaign and the RNC got more and more incendiary in the weeks after the election, so much so that the direct mail services for both, Iterable and Salesforce, rejected some ads for Terms of Service violations, and actually shut down RNC ads for a brief period after the attack.

The Select Committee interviewed an individual (“J. Doe”) who worked at Salesforce during the post-election period during which TMAGAC was sending out the fundraising emails concerning false election fraud claims.147 Doe worked for Salesforce’s privacy and abuse management team, colloquially known as the abuse desk.148 An abuse desk is responsible for preventing fraud and abuse emanating from the provider’s user or subscriber network.

Doe indicated to the Select Committee that, as soon as early 2020, they recalled issues arising with the RNC’s use of Salesforce’s services and that a“deluge of abuse would’ve started in June-ish.”149 Doe noted that Salesforce received a high number of complaints regarding the RNC’s actions, which would have been primarily the fundraising efforts of TMAGAC.150 In the latter half of 2020, Doe noticed that the emails coming from the RNC’s account included more and more violent and inflammatory rhetoric in violation of Salesforce’s Master Service Agreement (“MSA”) with the RNC, which prohibited the use of violent content.151 Doe stated that, near the time of the election, they contacted senior individuals at Salesforce to highlight the “increasingly concerning” emails coming from the RNC’s account.152 Doe explained that senior individuals at Salesforce effectively ignored their emails about TMAGAC’s inflammatory emails 153 and Salesforce ignored the terms of the MSA and permitted the RNC to continue touse its account in this problematic manner.154 Doe said, “Salesforce very obviously didn’t care about anti-abuse.”155

[snip]

Further, J. Doe, the Salesforce employee interviewed by the Select Committee, provided insight into the action that Salesforce took after the attack. Doe explained that after they became aware of the ongoing attack, they (Doe) took unilateral action to block the RNC’s ability to send emails through Salesforce’s platform.227 Doe noted that the shutdown lasted until January 11, 2021, when senior Salesforce leadership directed Doe to remove the block from RNC’s Salesforce account.228 Doe stated that Salesforce leadership told Doe that Salesforce would now begin reviewing RNC’s email campaigns to “make sure this doesn’t happen again.”229

Remember: The RNC successfully fought a subpoena from the J6C, which kept Salesforce information out of the hands of the Committee. They would have no such opportunity with a d-order from DOJ, though, and those records would show the same kind of awareness at Salesforce as Twitter and Facebook had that permitting Trump’s team to abuse the platform contributed to the violence.

After raising all this money, Trump reportedly then used it for purposes not permitted under campaign finance laws.

There was even a hilarious exchange from a Cannon deposition about how, as a lawyer working for the campaign, he could claim privilege over a discussion with Jared Kushner about setting up a PAC that could not coordinate with the campaign.

The appendix in the report has more details about where the funds eventually ended up — for example, in Dan Scavino’s pocket, or that of Melania’s dress-maker, or legal defense in investigations of these very crimes.

For example, from July 2021 to the present, Save America has been paying approximately $9,700 per month to Dan Scavino,171 a political adviser who served in the Trump administration as White House Deputy Chief of Staff.172 Save America was also paying $20,000 per month to an entity called Hudson Digital LLC. Hudson Digital LLC was registered in Delaware twenty days after the attack on the Capitol, on January 26, 2021,173 and began receiving payments from Save America on the day it was registered.174 Hudson Digital LLC has received payments totaling over $420,000, all described as “Digital consulting.”175 No website or any other information or mention of Hudson Digital LLC could be found online.176 Though Hudson Digital LLC is registered as a Delaware company, the FEC ScheduleB listing traces back to an address belonging to Dan and Catherine Scavino.177

[snip]

Through October 2022, Save America has paid nearly $100,000 in “strategy consulting” payments to Herve Pierre Braillard,195 a fashion designer who has been dressing Melania Trump for years.196

[snip]

From January 2021 to June 2022, Save America has also reported over $2.1 million in “legal consulting.” Many firms perform different kinds of practice, but more than 67% of those funds went to law firms that are representing witnesses involved in the Select Committee’s investigation whowere subpoenaed or invited to testify.

CNN’s report notes that on the financial side of the investigation, DOJ has acquired some cooperating witnesses (the Report hints at who those might include — and Cannon seems to have exposure on the obstruction side of the investigation even while getting good press for refusing to certify Trump’s production to NARA on the stolen document side).

On top of being an entirely different kind of crime, the financial trail may be one area where it is easier to show pushback on Trump’s false claims.

But J6C didn’t include that in its referrals, perhaps in part because Trump relied on the advice of one of the main GOP campaign finance firms, Jones Day, for some of the later financial decisions.

In any case, it turns out (as with many parts of the investigation) DOJ has quietly been investigating this for some time. Which may make the financial side of the Trump’s claims a key part of proof available about his campaign’s awareness that he was lying.