When the Mueller team wrote the GRU indictment, they were hiding that Roger Stone might one day be included in it.

Last week, DOJ unsealed language making it clear that, when Mueller closed up shop in March 2019, they were still investigating whether Roger Stone was part of a conspiracy with Russia’s GRU to hack-and-leak documents stolen from the Democrats in 2016.

The Office determined that it could not pursue a Section 1030 conspiracy charge against Stone for some of the same legal reasons. The most fundamental hurdles, though, are factual ones.1279 As explained in Volume I, Section III.D.1, supra, Corsi’s accounts of his interactions with Stone on October 7, 2016 are not fully consistent or corroborated. Even if they were, neither Corsi’s testimony nor other evidence currently available to the Office is sufficient to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Stone knew or believed that the computer intrusions were ongoing at the time he ostensibly encouraged or coordinated the publication of the Podesta emails. Stone’s actions would thus be consistent with (among other things) a belief that he was aiding in the dissemination of the fruits of an already completed hacking operation perpetrated by a third party, which would be a level of knowledge insufficient to establish conspiracy liability. See State v. Phillips, 82 S.E.2d 762, 766 (N.C. 1954) (“In the very nature of things, persons cannot retroactively conspire to commit a previously consummated crime.”) (quoted in Model Penal Code and Commentaries § 5.03, at 442 (1985)).

1279 Some of the factual uncertainties are the subject of ongoing investigations that have been referred by this Office to the D.C. U.S. Attorney’s Office.

That means, eight months after they charged a bunch of GRU officers for the hack-and-leak, DOJ still hadn’t decided whether Stone had criminally participated in that very same conspiracy.

That raises questions about why they obtained the indictment before deciding whether to include Stone in it.

In his book, Andrew Weissmann provides an explanation for the timing of it.

A problem arose, however, when it came to the timing of this indictment. Having secured the Intelligence Community’s and Justice Department’s go-ahead, Jeannie aimed to have the indictment completed by July 2018. However, Team M’s first case against Manafort was scheduled to go to trial in Virginia in mid-July and, with Manafort showing little sign of wanting to plead, much less cooperate, with our office, we had few doubts that the trial would go forward. If we brought Team R’s indictment just before the trial, the judge in the Manafort case would go bonkers, justifiably concerned that such an indictment from the Special Counsel’s Office could generate adverse pretrial publicity, even if it didn’t relate directly to the Manafort charges.

But we couldn’t afford to wait to bring the hacking indictment until after both of Manafort’s trials concluded—the trial in Virginia was slated to start in July and the trial in Washington in early September. By then, we would be running up on the midterms, and we would not announce any new charges that close to the election (consistent with Department policy). But waiting until mid-November would be intolerable to Mueller. I told Jeannie I thought we could safely defend ourselves from any objections from the Virginia judge if she brought her case at least two weeks before the start of our July trial—that, I hoped, would give us a reasonable buffer.

Jeannie said she could manage that, then quickly noted that the new timetable created yet another problem: Two weeks before our trial, the president was scheduled to be in Helsinki, where he would be meeting privately with Vladimir Putin. Our indictment would require alerting the State Department, given their diplomatic concerns in preparing for and running a summit, as the indictment would accuse the Russians explicitly of election interference. That was standard operating procedure, but there was also the real perception issue that the indictment could look like a commentary on Trump’s decision to meet alone with Putin, which we did not intend.

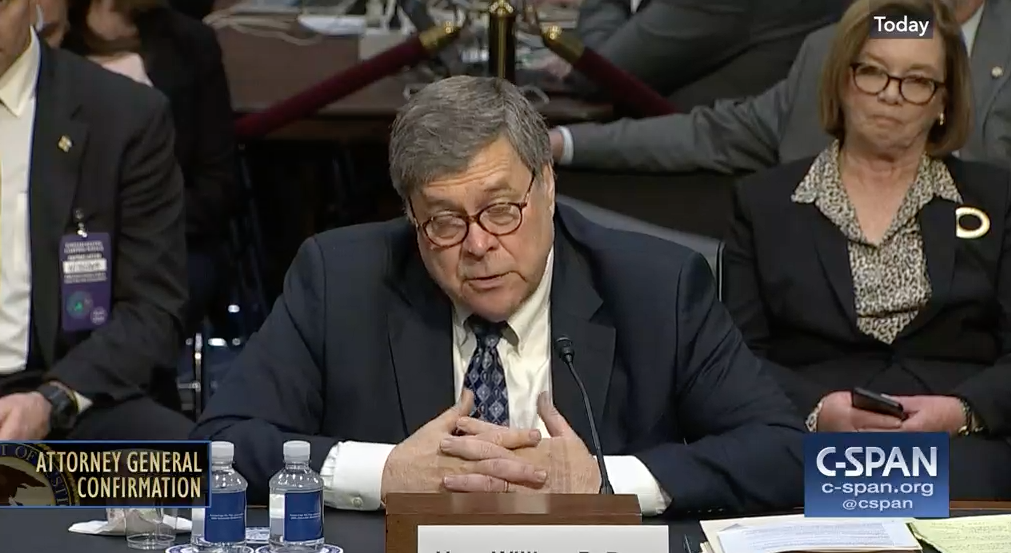

We brought the dilemma to Mueller. He suggested we determine whether the White House would take issue with our proceeding just before the president’s trip—would it pose any diplomatic issues? The answer we got back was no: The administration would not object to the timing. I suspect the White House Counsel’s Office did not want to be perceived as dictating to us how or when to bring our indictment, or as hiding evidence of Russian election interference. In retrospect, a less generous interpretation of their blessing to move forward was that they knew dropping the indictment just before the trip would provide Trump and Putin an opportunity to jointly deny the attack on a global stage—that they were playing us, as Barr would later on. [my emphasis]

The indictment was ready in July. If it wasn’t announced then and if both Manafort trials went forward, then prohibitions on pre-election indictments would kick in, meaning the indictment wouldn’t be released in mid-November. That would have been “intolerable” for Mueller’s purposes. Weissmann doesn’t note that mid-November would also be after the election, meaning that the indictment might not get released before a hypothetical post-election Mueller firing and so might not get released at all. That may be what intolerable means.

Other possible factors on the GRU indictment timing

One thing that almost certainly played a factor in DOJ obtaining the indictment before they decided whether to include Stone in it, however, was Andrew Miller’s appeal.

Stone’s former aide Andrew Miller was interviewed for two hours at his home on May 9, 2018; this is almost certainly the 302 from the interview. Assuming that is his 302, Miller was asked about his relationship with Stone, Stone’s relationship with Trump, a bunch of Stone’s right wing nut-job friends, and someone whom Miller knew under a different name. Nothing in the unredacted passages of the interview reflects Miller’s role coordinating Stone’s schedule at the RNC, even though that was the focus of a follow-up subpoena after Miller testified to the grand jury. At the end of the interview, Miller agreed to appear voluntarily for a follow-up and grand jury testimony.

But then Stone learned about the interview.

We know that from the description of a pen register Mueller obtained on Stone a week later, described in affidavits. The PRTT showed that Miller had called Stone twice in the days after his interview with the FBI. On May 11, 2018, Miller lawyered up and his new lawyer, Alicia Dearn, told Mueller that Miller would no longer appear voluntarily (remember that Stone had offered to get a lawyer who would help Randy Credico refuse to testify).

This timeline lays out the early part of Miller’s subpoena challenge.

Miller emailed Stone over a hundred times over the month after his FBI interview. Miller did schedule a grand jury appearance, but then blew it off. Mueller started moving to hold Miller in contempt on June 11. In the days between then and a hearing on the subpoena, Miller and Stone exchanged five more emails. Then, in late June, Miller added another lawyer, Paul Kamenar (whom Stone would add to his team after his sentencing, presumably to allow Kamenar to access the evidence against him under the protective order). Kamenar made it clear he would appeal Miller’s subpoena.

In other words, in late June, the Mueller team learned that they would have to wait a while to get Miller before the grand jury (it ultimately took until the moment Mueller closed up shop on May 29, 2019). All the back and forth also would have made it clear how damaging Stone believed Miller’s testimony against him to be. When Mueller obtained a second warrant for Stone’s emails in early August 2018, the team would have gotten the content of those emails to learn precisely what Stone had to say to Miller about his testimony.

So Miller’s challenge to his subpoena meant that Mueller’s team would not obtain testimony that — it seems clear — they knew went to the heart of whether Stone was conspiring with Russia until well after the midterm election.

If my concerns that “Phil” had a role in the Guccifer 2.0 operation were correct, there’s a chance my big mouth had a role in the timing, too. Starting on June 28, I started considering revealing that I had gone to the FBI in what would eventually become this post. Contrary to the invented rants of people like Glenn Greenwald and Eli Lake, even a year into an investigation into what I had shared with the FBI, long after the time they would have been able to dismiss my concerns if they had no merit, prosecutors did not blow me off.

My interaction with Mueller’s press person in advance of going forward extended over five days. I emailed the press person on June 28 and said I wanted to run something by him. He blew it off for a day (there was a Manafort hearing), then on Friday I wrote again saying I run my decision by my lawyer, and was still planning on going forward. He still blew it off. The next day, I suggested he go check with a particular prosecutor; while the prosecutor hadn’t been in my interview, he was involved in setting it up. The press guy called back within an hour, far more interested in the discussion, and chatty about the fact that I live(d) in Michigan. He asked me to explain the threats I believed I had gotten after I went to the FBI. He asked me generally what I wanted to say. I noted that I believed if people guessed why I had gone to the FBI, they would guess the Shadow Brokers side of it, since TSB had dedicated its last words to a tribute to me, but probably not the Guccifer 2.0 side.

He told me “some people” needed to discuss it. Early on Monday July 1, we spoke again first thing in the morning. He asked me to describe more specifically what I would say. I described the select parts of my post that I suspected would be most sensitive, and read the text that I planned to publish. He said some people needed to discuss it and I would hear by the end of the day. At the end of the workday, he apologized for a further delay. After some more back-and-forth, he told me, around 10PM, that my post would not damage the investigation. The Special Counsel’s Office took no view on whether it was a stupid idea or not (it probably was, not least because one can never understand the moving parts in an investigation like this).

I posted the next day, part of a mostly-failed attempt to get Republicans to care about the non-partisan sides of this investigation. That was 11 days before the actual indictment.

I didn’t know then and frankly I still can’t rule out whether, over those two days, when “some people” discussed my plans, they reached a final conclusion that my concerns about an American who might have a role in the Guccifer 2.0 operation were either baseless or could not be proven.

But the aftermath shows they were still investigating Stone’s ties to Guccifer 2.0, whether not I was right about an American involved in it. Later in July, after the GRU indictment was released, prosecutors would obtain a warrant on several of Stone’s Google accounts in an attempt to determine whether he was the person looking up dcleaks and Guccifer 2.0 before the sites went live. A month and a half later, they would get two warrants, two minutes apart, one for Stone’s cell site location, and another for a Guccifer 2.0 email account, possibly an attempt to co-locate Stone and someone using the Guccifer account. That was the beginning of the period when Mueller’s team would start gagging warrant applications to hide the scope of the investigation from Stone.

For several months after releasing an indictment that made it appear as if all the answers about the hack-and-leak were answered, then, Mueller’s team took a number of steps that aimed to understand any tie between Stone and Guccifer 2.0. Even sixteen months after the GRU indictment, the Guccifer 2.0 persona ended up being an unstated focus of Stone’s trial — a trial about his lies to hide his true go-between with WikiLeaks — too.

Whatever the reason for the timing of the GRU indictment, given the confirmation that Mueller’s team was still investigating whether Stone had foreknowledge of ongoing GRU hacks that would merit including him in the hack-and-leak conspiracy when they closed up shop in March 2019, it’s worth revisiting the GRU indictment. At the time Mueller’s team wrote it, they knew at a minimum they were killing time to get Miller’s testimony, and subsequent steps they took show they they continued to pursue a prong of the investigation pertaining to Guccifer 2.0 that they planned to hide from Stone. So it’s worth seeing how they wrote the indictment to allow for the possibility of later including Stone in it, without telegraphing that that was a still open part of the investigation.

The Stone investigation parallels several of the counts charged in Mueller’s GRU indictment

The indictment charges 12 GRU officers for several intersecting conspiracies: Conspiracy against the US by hacking to interfere in the 2016 election (incorporating various CFAA charges and 18 USC §371), conspiracy to commit wire fraud for using false domain names (18 USC §3559(g)(1)), aggravated identity theft for stealing the credentials of victims (18 USC 1028A(a)(1)), conspiracy to launder money for using bitcoin to hide who was funding the hacking infrastructure (18 USC §1956(h)), and conspiracy against the US for tampering with election infrastructure (18 USC §371). In addition there’s an abetting charge (18 USC §2). Those charges are similar to, but do not exactly line up with, the other GRU indictment obtained in 2018, for hacking international doping agencies, which I’ll call the WADA indictment. The WADA indictment includes hacking, wire fraud, money laundering conspiracies, along with identity theft, as well. But it doesn’t include the abetting charge. And as described below, it deals with the leaking part of the operation differently.

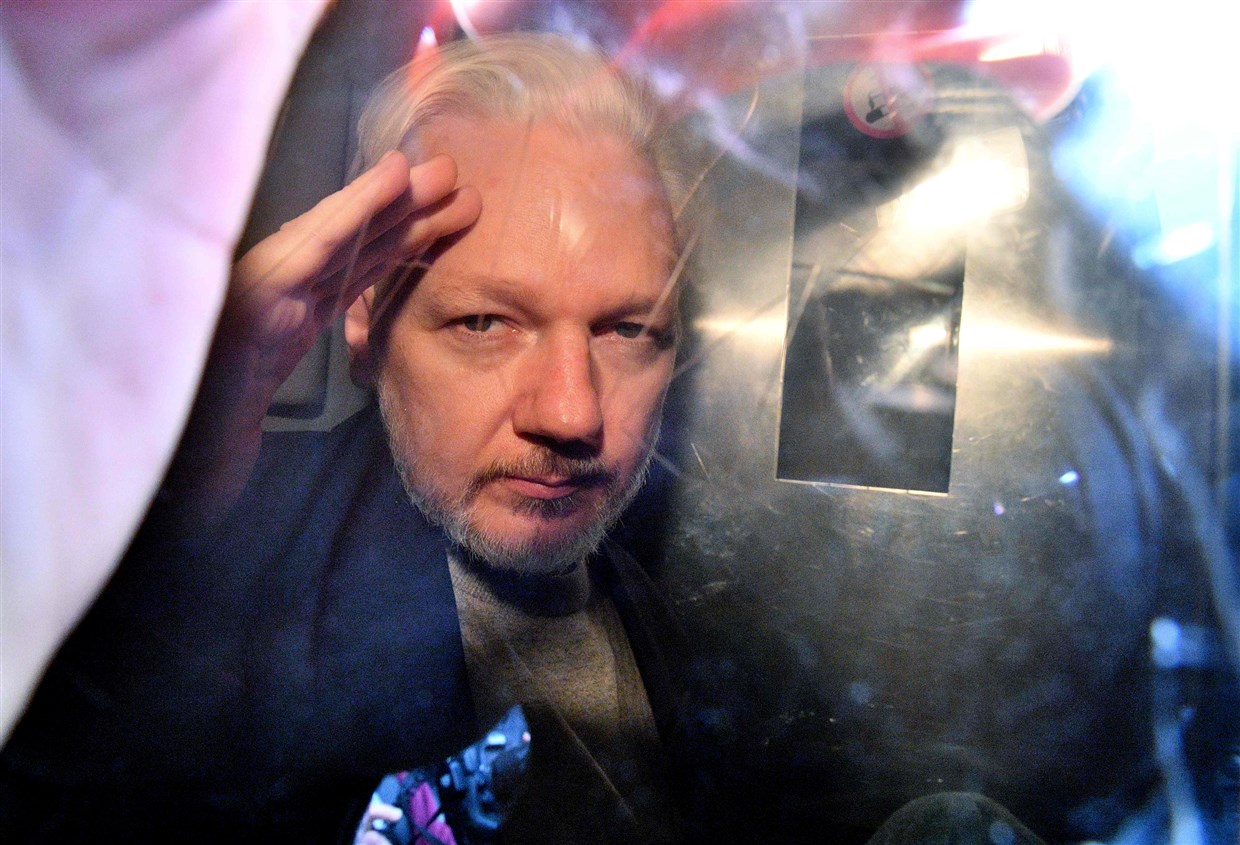

DOJ used the abetting charge in Julian Assange’s indictments, a way to try to hold him accountable for the theft of documents by Chelsea Manning. Given the mention of Company 1, WikiLeaks, in the indictment, that may be why the abetting charge is there.

But the charges in the Mueller GRU indictment also parallel those for which the office was investigating Stone: he was investigated for CFAA charges from the start (that first affidavit focused exclusively on Guccifer 2.0), 371 was added in the next affidavit, aiding and abetting a conspiracy was added in the third affidavit, and wire fraud was added in March 2018 (the campaign finance charges that would be declined in the Mueller Report were added in November 2017). While the wire fraud investigation might be tied to Stone’s own disinformation on social media, the rest all stems from the charges eventually filed against the GRU in July 2018. Those same charges remained in Stone’s affidavits through 2018 (though did not appear in the early 2019 warrants used to search his houses and devices).

Mueller charged Unit 74455 officers for “assisting” in the DNC leak, without describing whom they assisted

Given the overlap on charges between those for which Mueller investigated Stone and those that appeared in the indictment, the treatment of the information operation in the GRU indictment — particularly when compared with the WADA indictment — is of particular interest. In both cases, the indictment described the InfoOps side to be conducted by Russian military intelligence GRU Unit 74455, as distinct from Unit 26165, which did most (but not all, in the case of the election operation) of the hacking.

In the WADA indictment, none of the personnel involved in the hack-and-leak at Unit 74455 are named or charged. Instead the indictment explains that, “these [Fancy Bears Hack Team social media accounts] were acquired and maintained by GRU Unit 74455.” Later, the indictment describes these accounts as being “managed, at least in part, by conspirators in GRU 74455,” notably allowing for the possibility that someone else may have been involved as well. The actions associated with that infrastructure are generally described in the passive voice: “were registered,” “were released” (several times). For other actions, the personas were the subject of the action: “”@fancybears and @fancybearHT Twitter accounts sent direct messages…”

The Mueller indictment, however, names three Unit 74455 officers: It charges Aleksandr Osadchuk and Anatoliy Kovalev in the hack of the election infrastructure (Kovalev got charged in the recent GRU indictment covering the Seoul Olympics and NotPetya, as well).

And it charges Osadchuk and the improbably named Aleksey Potemkin in the hack-and-leak conspiracy. The Mueller indictment describes that those two Unit 74455 officers set up the infrastructure for the leaking part of the operation. Significantly, it describes that these officers “assisted” in the release of the stolen documents.

Unit 74455 assisted in the release of stolen documents through the DCLeaks and Guccifer 2.0 personas, the promotion of those releases, and the publication of anti-Clinton content on social media accounts operated by the GRU.

[snip]

Infrastructure and social media accounts administered by POTEMKIN’s department were used, among other things, to assist in the release of stolen documents through the DCLeaks and Guccifer 2.0 personas.

The indictment doesn’t describe whom these officers assisted in releasing the documents.

Unlike the WADA indictment, the Mueller indictment also includes specific details proving that GRU did control the social media infrastructure. It describes how the conspirators used the same cryptocurrency account to register “dcleaks.com” as they used in the spear-phishing operation, and the same email used to register the server was also used in the spear-phishing effort.

The funds used to pay for the dcleaks.com domain originated from an account at an online cryptocurrency service that the Conspirators also used to fund the lease of a virtual private server registered with the operational email account [email protected]. The dirbinsaabol email account was also used to register the john356gh URL-shortening account used by LUKASHEV to spearphish the Clinton Campaign chairman and other campaign-related individuals.

[snip]

For example, between on or about March 14, 2016 and April 28, 2016, the Conspirators used the same pool of bitcoin funds to purchase a virtual private network (“VPN”) account and to lease a server in Malaysia. In or around June 2016, the Conspirators used the Malaysian server to host the dcleaks.com website. On or about July 6, 2016, the Conspirators used the VPN to log into the @Guccifer_2 Twitter account. The Conspirators opened that VPN account from the same server that was also used to register malicious domains for the hacking of the DCCC and DNC networks.

(Note, this is some of the evidence collected via subpoenas to tech companies that the denialists ignore when they claim that CrowdStrike was the only entity to attribute the effort to Russia.)

The Mueller indictment describes how Potemkin controlled the computers used to launch the dcleaks Facebook account.

On or about June 8, 2016, and at approximately the same time that the dcleaks.com website was launched, the Conspirators created a DCLeaks Facebook page using a preexisting social media account under the fictitious name “Alice Donovan.” In addition to the DCLeaks Facebook page, the Conspirators used other social media accounts in the names of fictitious U.S. persons such as “Jason Scott” and “Richard Gingrey” to promote the DCLeaks website. The Conspirators accessed these accounts from computers managed by POTEMKIN and his co-conspirators.

Finally, there’s the most compelling evidence, that some conspirators logged into a Unit 74455-controlled server in Moscow hours before the initial Guccifer 2.0 post went up and searched for the phrases that would be used in the first post.

On or about June 15, 2016, the Conspirators logged into a Moscow-based server used and managed by Unit 74455 and, between 4:19 PM and 4:56 PM Moscow Standard Time, searched for certain words and phrases, including:

Search Term(s)

“some hundred sheets”

“some hundreds of sheets”

dcleaks

illuminati

широко известный перевод [widely known translation]

“worldwide known”

“think twice about”

“company’s competence”

Later that day, at 7:02 PM Moscow Standard Time, the online persona Guccifer 2.0 published its first post on a blog site created through WordPress. Titled “DNC’s servers hacked by a lone hacker,” the post used numerous English words and phrases that the Conspirators had searched for earlier that day (bolded below):

Worldwide known cyber security company [Company 1] announced that the Democratic National Committee (DNC) servers had been hacked by “sophisticated” hacker groups.

I’m very pleased the company appreciated my skills so highly))) [. . .]

Here are just a few docs from many thousands I extracted when hacking into DNC’s network. [. . .]

Some hundred sheets! This’s a serious case, isn’t it? [. . .] I guess [Company 1] customers should think twice about company’s competence.

F[***] the Illuminati and their conspiracies!!!!!!!!! F[***] [Company 1]!!!!!!!!! [emphasis original]

Remember: in the weeks after DOJ released this indictment, Mueller’s team took steps to try to obtain proof of whether Roger Stone was the person in Florida searching on Guccifer’s moniker on June 15, 2016, before the initial post was published. If Stone did learn about this effort in advance, it would suggest he learned about Guccifer 2.0 operation around the same time as someone was searching on these phrases in a GRU server located in Moscow. It would mean Stone learned about the upcoming Guccifer post in the same timeframe as these GRU officers were reviewing it.

It’s not really clear what was going on here. The assumption has always been that GRU officers were looking for translations into English from a post they drafted in Russian, even though the quotation marks suggests the Russian officers were searching on English phrases.

The one exception to that seems to confirm that. Those conducting these searches appear to have searched on a Russian phrase, a phrase they would have easily understood.

широко известный перевод

Moreover, it would take a shitty-ass translation application to come up with the stilted English used in the post. Plus, “illuminati,” at least, is an easily recognized cognate, even for someone (me!) whose Russian is surely worse than the English of any one of these Russian intelligence officers.

Still, proof of this activity — obtained via undescribed means — clearly ties the Guccifer operation to the GRU. It’s just not clear what to make of it. And the possibility that there’s an American component to the Guccifer 2.0 operation — whether “Phil” or someone else — one that may have alerted Stone to what was going on, provides explanations other than straight up translation. Indeed, it may be that GRU officers were approving the content that someone else wrote, originally in English. Which might also explain why Stone may have known about it in advance.

Whatever else, the GRU indictment only claims that these GRU officers “assisted” this effort. It doesn’t claim they wrote this post.

The Stone-adjacent Guccifer 2.0 activity

One other detail of Mueller’s GRU indictment of interest pertains to which Stone-adjacent activity it chose to highlight.

Stone had first made his DMs with Guccifer 2.0 public himself, in March 2017. They were covered in his House Intelligence Committee testimony. But when Mueller included them in the GRU indictment, Stone first denied, and then sort of conceded the reference to them might be him. His initial denial was an attempt to deny he had spoken with people in the campaign other than Trump himself, even though he had released the communications himself over a year earlier.

Remember — Mueller was still weighing whether Stone was criminally involved in this conspiracy when Stone issued the initial denial!

But that’s not the most interesting detail of the part of the indictment that lays out with whom Guccifer 2.0 shared stolen documents (even ignoring one or two tidbits I’m still working on).

Mueller’s GRU indictment included — along with the reference to the Roger Stone DMs they still hadn’t determined whether reflected part of a criminal conspiracy or not — the Lee Stranahan exchange with Guccifer 2.0 that ended in Stranahan, a Breitbart employee who would later move to Sputnik, obtaining early copies of a document purportedly about Black Lives Matter.

On or about August 22, 2016, the Conspirators, posing as Guccifer 2.0, sent a reporter stolen documents pertaining to the Black Lives Matter movement. The reporter responded by discussing when to release the documents and offering to write an article about their release.

These Stranahan exchanges are really worth attention, not just for the way they prove that Stone-adjacent people got early releases on request (which, lots of evidence suggests, also happened with Stone with respect to the Podesta files pertaining to Joule Holdings), but also for the way Guccifer 2.0 ignored Stranahan’s claim in early August 2016 to have convinced Stone that Guccifer 2.0 was not Russian.

Note what this indictment didn’t mention, though: Guccifer 2.0’s outreach to Alex Jones (about whom, unlike Stranahan, the FBI questioned Andrew Miller).

As I’ve pointed out, in the SSCI Report, there’s a long section on Jones that remains almost entirely redacted. Citing to five pages of a report the title of which is also redacted, the four paragraphs appear between the discussions of Guccifer 2.0’s outreach to then-InfoWars affiliate Roger Stone and Guccifer 2.0 and dcleaks’ communication with each other.

According to Thomas Rid’s book, Active Measures, both dcleaks and Guccifer 2.0 tried to reach out to Jones on October 18, 2016.

On October 18, for example, as the election campaign was white hot and during the daily onslaught of Podesta leaks, both GRU fronts attempted to reach out to Alex Jones, a then-prominent conspiracy theorist who ran a far-right media organization called Infowars. The fronts contacted two reporters at Infowars, offered exclusive material, and asked to be put in touch with the boss directly. One of the reporters was Mikael Thalen, who then covered computer security. First it was DCleaks that contacted Thalen. Then, the following day, Guccifer 2.0 contacted him in a similar fashion. Thalen, however, saw through the ruse and was determined not to “become a pawn” of the Russian disinformation operation; after all, he worked at Infowars. So Thalen waited until his boss was live on a show and distracted, then proceeded to impersonate Jones vis-à-vis the Russian intelligence fronts.23

“Hey, Alex here. What can I do for you?” the faux Alex Jones privately messaged to the faux Guccifer 2.0 on Twitter, later on October 18.

“hi,” the Guccifer 2.0 account responded, “how r u?”

“Good. Just in between breaks on the show,” said the Jones account. “did u see my last twit about taxes?”

Thalen, pretending to be Jones, said he didn’t, and kept responses short. The officers manning the Guccifer 2.0 account, meanwhile, displayed how bad they were at media outreach work, and consequently how much value Julian Assange added to their campaign. “do u remember story about manafort?” they asked Jones in butchered English, referring to Paul Manafort, Donald Trump’s former campaign manager. But Thalen no longer responded. “dems prepared to attack him earlier. I found out it from the docs. is it interesting for u?”24

Rid describes just one of two outreaches to Jones (through his IC sources, he may know of the report the SSCI relies on). But a key detail is that this outreach used as entrée some stolen documents from May 2016 showing that the Democrats were doing basic campaign research on Trump’s financials. It then purports to offer “Alex Jones” information on early Democratic attacks on Paul Manafort’s substantial Ukrainian graft, possibly part of the larger GRU effort to claim that Ukraine had planned an election year attack on Trump.

That is, unlike Stranahan’s request for advance documents, this discussion intended for “Alex Jones,” ties directly to Stone’s efforts to optimize the Podesta release. And it’s something that some entity prevented SSCI from publishing.

It’s also something Mueller’s team left out of an indictment aiming to lay out the hack-and-leak case before they might get fired, but in such a way as to hide the then-current state of the investigation from Roger Stone.

There were actually a number of Stone-adjacent associates in contact with GRU’s personas. And as recently as just a few months ago, the government wanted to hide the nature of those ties.