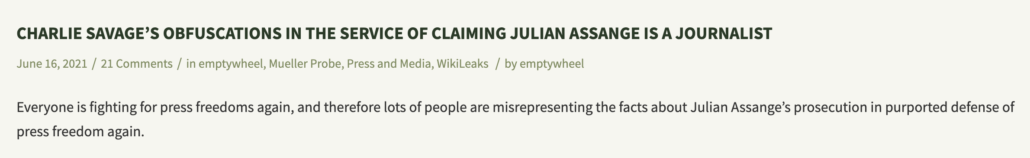

NARA May Have Pre-Existing Legal Obligations with Respect to Documents Covered by Aileen Cannon’s Order

On Monday, Aileen Cannon told the government that it can only access 11,282 documents legally owned by the National Archives and currently possessed by DOJ to do an assessment of the damage Trump did by storing those records in a poorly-secured storage closet and desk drawer.

We’ll learn more in coming days about how the government will respond to Cannon’s usurpation of the President’s authority over these documents.

But I want to note that there may be competing legal obligations, on NARA at least, that may affect the government’s response.

NARA has been responding to at least four pending legal obligations as the fight over Trump’s stolen documents has gone on:

- A series of subpoenas from the January 6 Committee that the Supreme Court has already ruled has precedence over any claims of privilege made by Trump

- Two subpoenas from DOJ’s team investigating January 6, one obtained in May, covering everything NARA has provided to the J6C, and a second one served on NARA on August 17; these subpoenas would also be covered under SCOTUS’ ruling rejecting Trump’s privilege claims

- Discovery in Tom Barrack’s case, whose trial starts on September 19 (DOJ informed Barrack they had requested Trump White House materials from NARA on April 5)

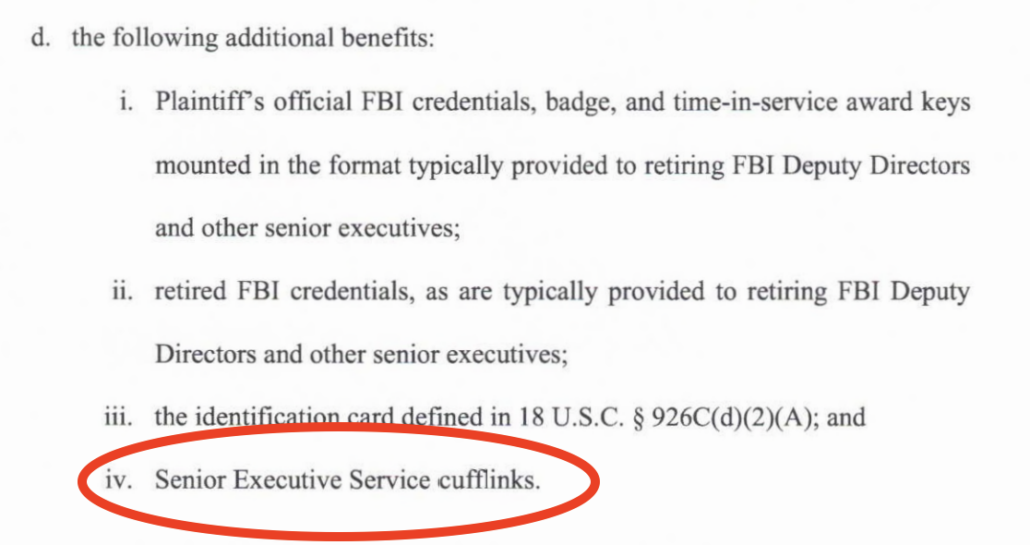

- A subpoena from Peter Strzok in his lawsuit over his firing and privacy act violations

For all of them, NARA has a legal obligation that precedes Judge Cannon’s order. So if any of the material owned by NARA that Cannon has enjoined for Trump’s benefit is covered by these subpoenas and the Barrack discovery request, it will give NARA an additional need to intervene, on top of the fact that Cannon has made decisions about property owned by NARA.

I don’t hold out hope that the August 8 seizure has much pertaining to either January 6 investigation. Given that none of the boxes include clippings that post-date November, its unlikely they include government documents from the same period.

Plus, given the timing, I suspect the more recent subpoena from Thomas Windom to NARA pertains to materials turned over to NARA by Mark Meadows after the Mar-a-Lago search. Because Meadows originally turned those communications over to J6C directly, they would not have been covered by the prior subpoena, which obtained everything NARA turned over to J6C, which wouldn’t have included Meadows’ texts.

Meadows’ submission to the Archives was part of a request for all electronic communications covered under the Presidential Records Act. The Archives had become aware earlier this year it did not have everything from Meadows after seeing what he had turned over to the House select committee investigating January 6, 2021. Details of Meadows’ submissions to the Archives and the engagement between the two sides have not been previously reported.

“It could be a coincidence, but within a week of the August 8 search on Mar-a-Lago, much more started coming in,” one source familiar with the discussions said.

The second subpoena would have been served days after Meadows started providing these texts.

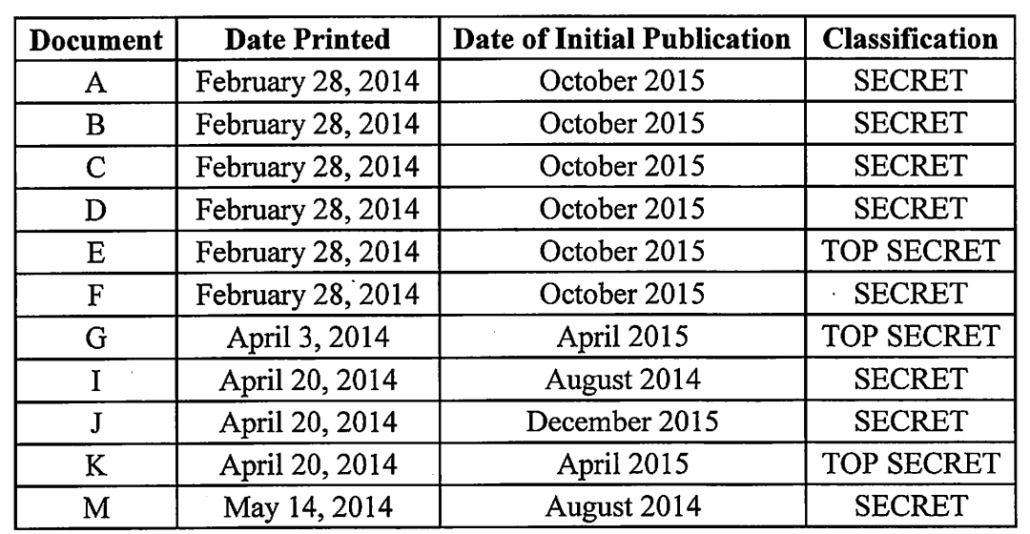

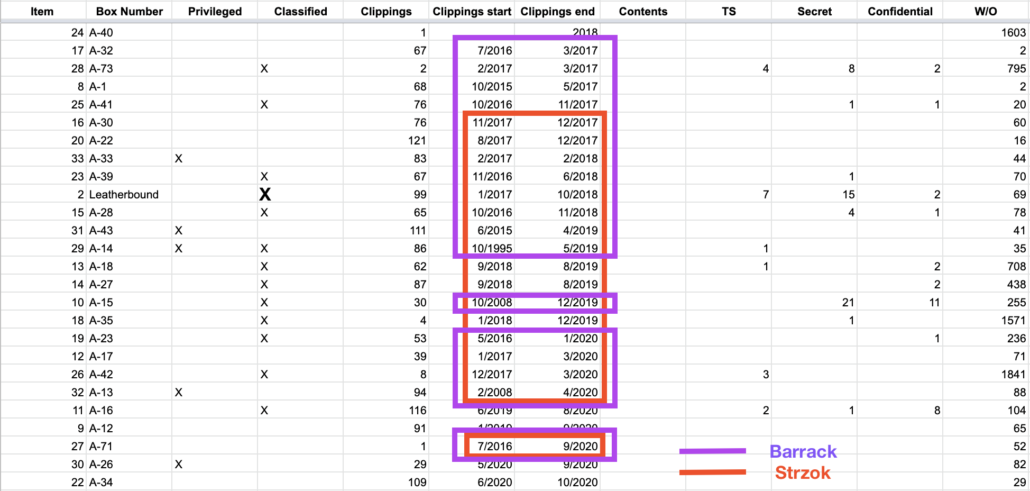

The possibility that some of the documents seized on August 8 would be discoverable in Barrack’s case is likely higher, particularly given the news that Trump had hoarded at least one document about “a foreign government’s nuclear-defense readiness.” Barrack is accused of working to influence White House policy on issues pertaining to UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar that might be implicated by classified documents. If the date of clippings in a particular box reflect the age of the government documents also found in that box, then about 18 boxes seized in August (those marked in purple, above) include records from the period covered by Barrack’s superseding indictment.

That said, whether any such materials would count as being in possession of DOJ is another issue. They are currently in possession of team at DOJ that significantly overlaps with the people prosecuting Barrack for serving as an Agent of the Emirates without telling the Attorney General.

Strzok’s subpoena may be the most likely to cover materials either turned over belatedly or seized on August 8 (though his subpoena was scoped, with DOJ involvement, at a time after the FBI was aware of Trump’s document theft). It asks for:

- Records concerning Sarah Isgur’s engagement with reporters from the Washington Post or New York Times about Peter Strzok and/or Lisa Page on or about December 1 and 2, 2017.

- Records dated July 1, 2017 through December 12, 2017 concerning or reflecting any communications with members of the press related to Peter Strzok and/or Lisa Page.

- Records dated July 1, 2017 through December 12, 2017 concerning or reflecting text messages between Peter Strzok and Lisa Page.

- Records dated July 1, 2017 through August 9, 2018 concerning Peter Strzok’s employment at the FBI.

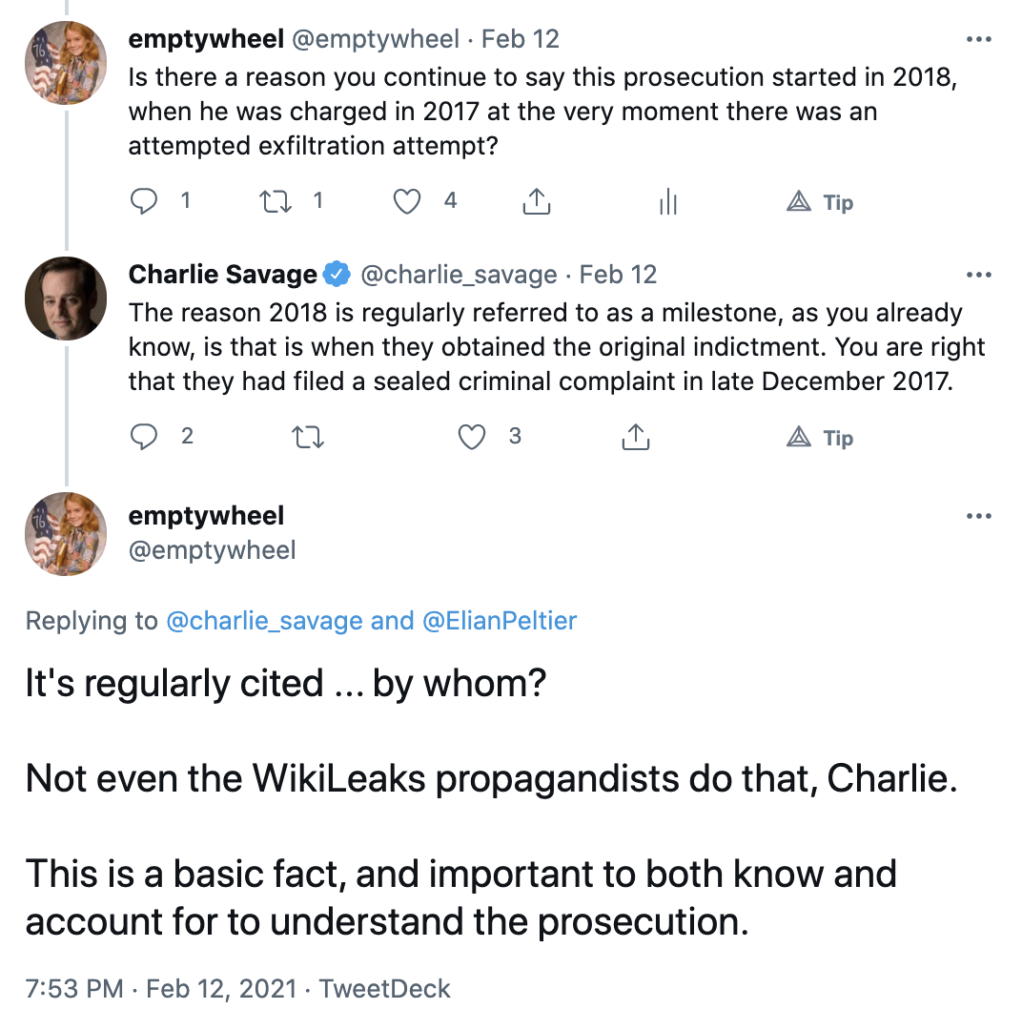

That materials covered by this subpoena made their way at some point to Mar-a-Lago is likely. That’s because of the obsession with records relating to Crossfire Hurricane in the days when Trump was stealing documents — virtually all of those would “concern” Strzok’s FBI employment.

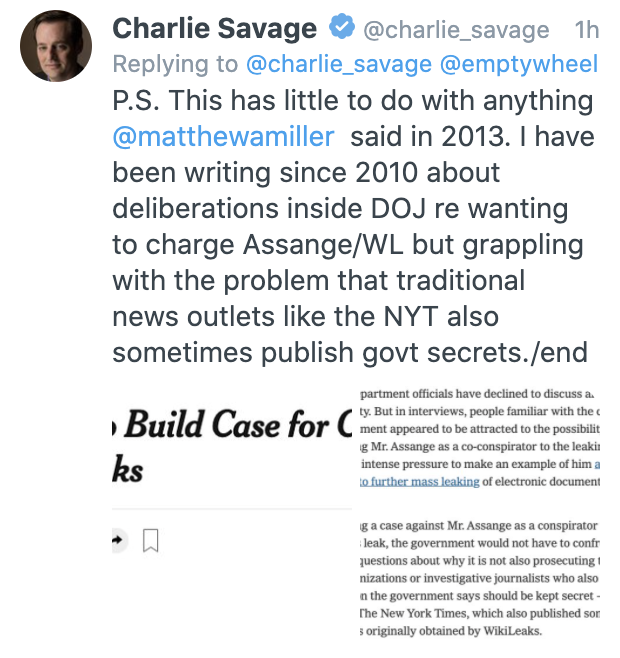

In Mr. Trump’s last weeks in office, Mr. Meadows, with the president’s blessing, prodded federal law enforcement agencies to declassify a binder of Crossfire Hurricane materials that included unreleased information about the F.B.I.’s investigative steps and text messages between two former top F.B.I. officials, Peter Strzok and Lisa Page, who had sharply criticized Mr. Trump in their private communications during the 2016 election.

The F.B.I. worried that releasing more information could compromise the bureau, according to people familiar with the debate. Mr. Meadows dismissed those arguments, saying that Mr. Trump himself wanted the information declassified and disseminated, they said.

Just three days before Mr. Trump’s last day in office, the White House and the F.B.I. settled on a set of redactions, and Mr. Trump declassified the rest of the binder. Mr. Meadows intended to give the binder to at least one conservative journalist, according to multiple people familiar with his plan. But he reversed course after Justice Department officials pointed out that disseminating the messages between Mr. Strzok and Ms. Page could run afoul of privacy law, opening officials up to suits.

None of those documents or any other materials pertaining to the Russia investigation were believed to be in the cache of documents recovered by the F.B.I. during the search of Mar-a-Lago, according to a person with knowledge of the situation.

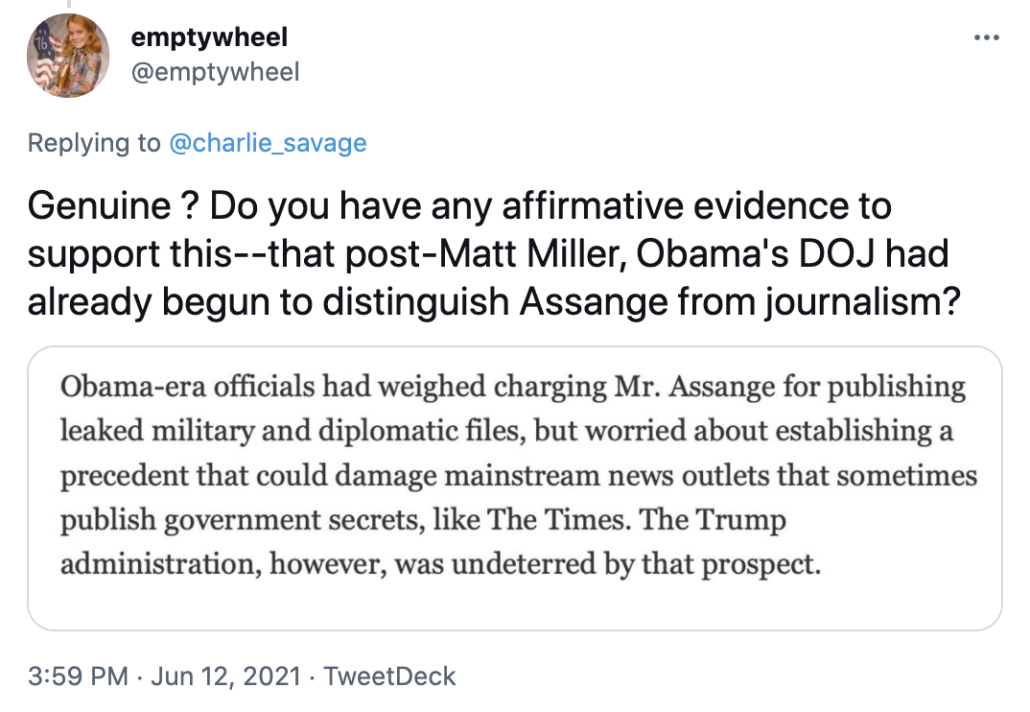

Side note: NYT’s sources are blowing smoke when they suggest DOJ under Trump would avoid new Privacy Act violations against Strzok and Page; a set of texts DOJ released on September 24, 2020 as part of Jeffrey Jensen’s effort to undermine the Mike Flynn prosecution had already constituted a new Privacy Act violation against them.

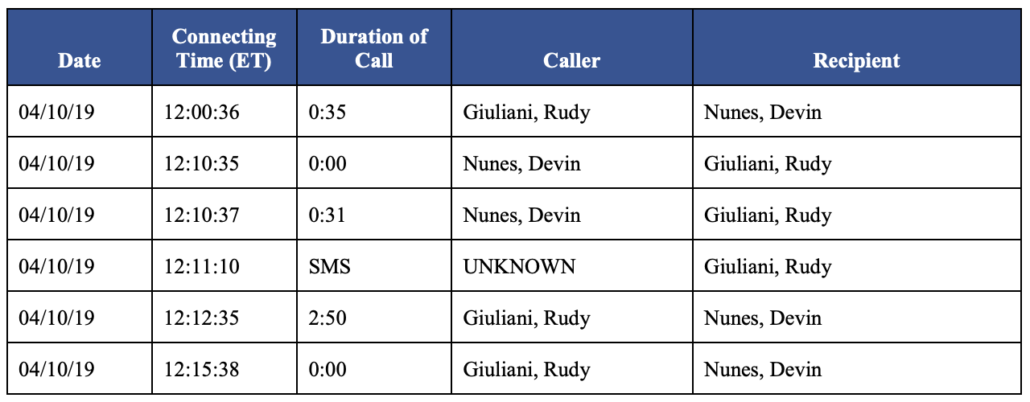

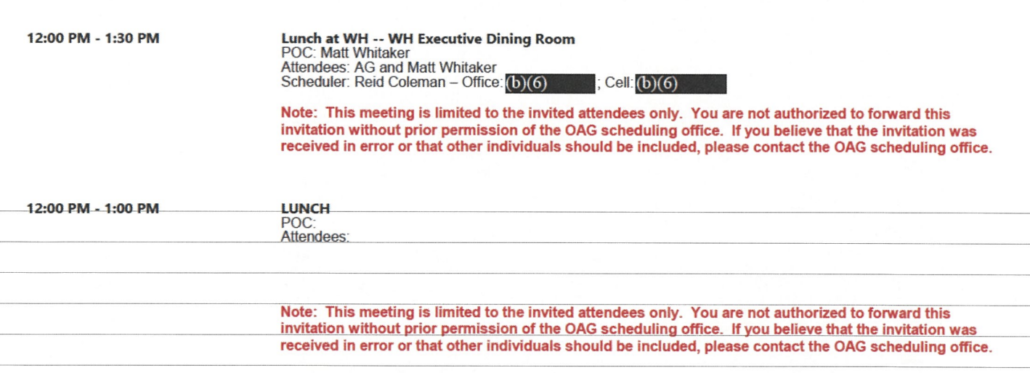

Notably, Strzok has been pursuing records about a January 22, 2018 meeting Jeff Sessions and Matt Whitaker attended at the White House.

Hours after that meeting (and a half hour call, from 3:20 to 3:50, between then Congressman Mark Meadows and the Attorney General), Jeff Sessions issued a press release about Strzok and Lisa Page.

Discovery has confirmed that the Attorney General released a press statement via email from Ms. Isgur to select reporters between 5:20 and 8:10 PM on January 22, roughly three hours after Attorney General Sessions returned from the White House. The statements promised, “If any wrongdoing were to be found to have caused this gap [in text messages between Mr. Strzok and Ms. Page], appropriate legal disciplinary action measure will be taken” and that the Department of Justice would “leave no stone unturned.” (See, e.g., Exhibit F). Based on Mr. Strzok’s review of the documents, it does not appear that this statement was planned prior to the January 22 White House meeting. It is not apparent from the documents produced in this action what deliberation lead to the issuance of that statement. For example, Mr. Strzok has not identified any drafts of the press release.

Any back-up to the White House side of that meeting — whether it has made its way back to NARA or not — would be included within the scope of Strzok’s subpoena. And even if NYT’s sources are correct that no Crossfire Hurricane documents were included among those seized in August (an uncertain claim given how much lying to the press Trump’s people have been doing), records covering Strzok’s firing would be broader than that.

The red rectangles, above, show the 17 documents seized in August for which the clippings would be in the temporal scope of Strzok’s subpoena.

I have no idea what happens if some of the boxes seized on August 8 include material responsive to these legal demands on NARA.

But if those boxes do include such materials, then it presents a competing — and pre-exisitng — legal obligation on the lawful owner of these records.

Update: Viget alerted me that I had not put an “X” by the leatherbound box reflecting its classified contents. I’ve fixed that!

![[Photo: National Security Agency, Ft. Meade, MD via Wikimedia]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/NationalSecurityAgency_HQ-FortMeadeMD_Wikimedia.jpg)