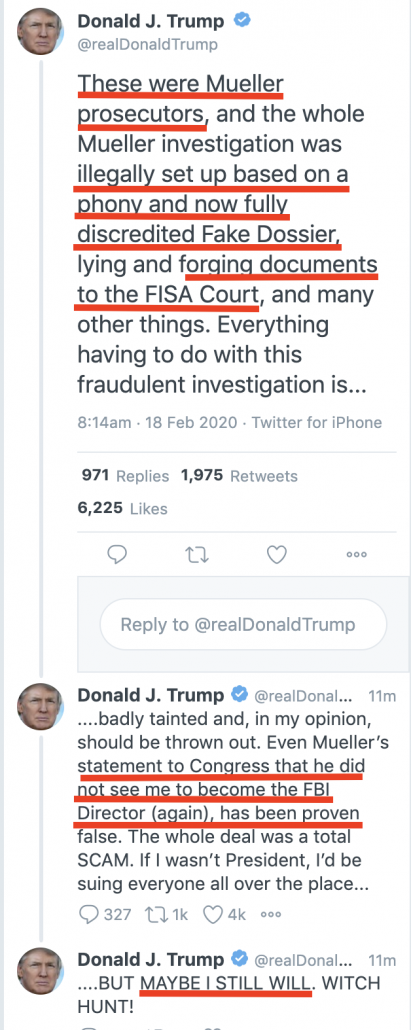

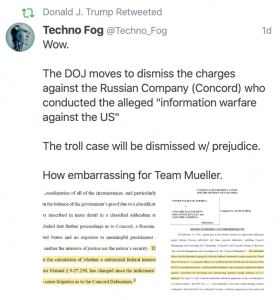

The frothy right and anti-Trump left both politicized DOJ’s decision to dismiss the single count of conspiracy charged against Concord Management and Concord Catering in the Russian troll indictment that Mueller’s team obtained on February 16, 2018. The right — including the President — and the alt-Left are falsely claiming the prosecution against all the trolls fell apart and suggesting this undermines the claims Russia tampered in the 2016 election.

The mainstream left speculated, without any apparent basis, that Bill Barr deliberately undermined the prosecution by classifying some of the evidence needed to prove the case.

The politicization of the outcome is unfortunate, because the outcome raises important policy questions about DOJ’s recent efforts to name-and-shame nation-state activities in cyberspace.

The IRA indictment intersects with a number of important policy discussions

The decision to indict the Internet Research Agency, its owner Yevgeniy Prigozhin, two of the shell companies he used to fund Internet Research Agency (Concord Management and Concord Catering, the defendants against which charges were dropped), and twelve of the employees involved in his troll operations intersects with three policy approaches adopted in bipartisan fashion in recent years:

- The use of indictments and criminal complaints to publicly attribute and expose the methods of nation-state hackers and the vehicles (including shell companies) they use.

- A recent focus on Foreign Agents Registration Act compliance and prosecutions in an attempt to crack down on undisclosed foreign influence peddling.

- An expansive view of US jurisdiction, facilitated but not limited to the role of the US banking system in global commerce.

There is — or should be — more debate about all of these policies. Some of the prosecutions the US has pursued (one that particularly rankles Russia is of their Erik Prince equivalent, Viktor Bout, who was caught in a DEA sting selling weapons to FARC) would instill outrage if other countries tried them with US citizens. Given the way Trump has squandered soft power, that is increasingly likely. While DOJ has obtained some guilty pleas in FARA cases (most notably from Paul Manafort, but Mike Flynn also included his FARA violations with Turkey in his Statement of the Offense), the FARA prosecutions of Greg Craig (which ended in acquittal) and Flynn’s partner Bijan Kian (which ended in a guilty verdict that Judge Anthony Trenga overturned) have thus far faced difficulties. Perhaps most problematic of all, the US has indicted official members of foreign state intelligence services for activities (hacking), though arguably not targets (private sector technology), that official members of our own military and intelligence services also hack. That’s what indictments (in 2014 for hacks targeting a bunch of victims, most of them in Pittsburgh and this year for hacking Equifax) against members of China’s People’s Liberation Army and Russia’s military intelligence GRU (both the July 2018 indictment for the hack-and-leak targeting the 2016 election and an October 2018 one for targeting anti-doping organizations) amount to. Those indictments have raised real concerns about our intelligence officers being similarly targeted or arrested without notice when they travel overseas.

The IRA indictment is different because, while Prigozhin runs numerous mercenary activities (including his Wagner paramilitary operation) that coordinate closely with the Russian state, his employees work for him, not the Russian state. But the Yahoo indictment from 2017 included both FSB officers and criminal hackers and a number of the hackers DOJ has otherwise indicted at times work for the Russian government. So even that is not unprecedented.

The indictment did serve an important messaging function. It laid out the stakes of the larger Russian investigation in ways that should have been nonpartisan (and largely were, until Concord made an appearance in the courts and started trolling the legal system). It asserted that IRA’s efforts to thwart our electoral and campaign finance functions amounted to a fraud against the United States. And it explained how the IRA effort succeeded in getting Americans to unwittingly assist the Russian effort. The latter two issues, however, may be central to the issues that undid the prosecution.

Make no mistake: the IRA indictment pushed new boundaries on FARA in ways that may raise concerns and are probably significant to the decision to drop charges against Concord. It did so at a time when DOJ’s newfound focus on FARA was not yet well-established, meaning DOJ might have done it differently with the benefit of the lessons learned since early 2018. Here’s a shorter and a longer version of an argument from Joshua Fattal on this interpretation of FARA. Though I think he misses something about DOJ’s argument that became clear (or, arguably, changed) last fall, that DOJ is not just arguing that the trolls themselves are unregistered foreign agents, but that they tricked innocent Americans into being agents. And DOJ surely assumed it would likely never prosecute any of those charged, unless one of the human targets foolishly decided to vacation in Prague or Spain or any other country with extradition treaties with the US. So the indictment was a calculated risk, a risk that may not have paid off.

But that’s why it’s worth understanding the decision to drop the prosecution based off the record, rather than presumptions about DOJ and the Russia investigation.

Just the funding side of the conspiracy to defraud indictment got dropped

The first step to understanding why DOJ dropped the charges is to understand what the two Concord entities were charged with. The indictment as a whole charged eight counts:

- Conspiracy to defraud the United States for preventing DOJ and FEC from policing our campaign finance and election system (and State for issuing visas)

- Conspiracy to commit wire fraud and bank fraud by using stolen identities to open financial accounts with which to evade PayPal’s security

- Six counts of aggravated identity theft for stealing the identities of Americans used in the wire and bank fraud

The wire and bank fraud charges remain untouched by DOJ’s decision. If any of those defendants shows up in court, DOJ remains fully prepared to hold them accountable for stealing Americans’ identities to thwart PayPal’s security protocols so as to fool Americans into doing Russia’s work. Such an identity theft prosecution would not rely on the aggressive FARA theory the Concord charge does.

Even still, most of the conspiracy to defraud (ConFraudUS) charge remains.

The two Concord entities were only named in the ConFraudUS charge. The overt acts involving Concord entail funding the entire operation and hiding those payments by laundering them through fourteen different affiliates and calling the payments “software support.”

3. Beginning as early as 2014, Defendant ORGANIZATION began operations to interfere with the U.S. political system, including the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Defendant ORGANIZATION received funding for its operations from Defendant YEVGENIY VIKTOROVICH PRIGOZHIN and companies he controlled, including Defendants CONCORD MANAGEMENT AND CONSULTING LLC and CONCORD CATERING (collectively “CONCORD”). Defendants CONCORD and PRIGOZHIN spent significant funds to further the ORGANIZATION’s operations and to pay the remaining Defendants, along with other uncharged ORGANIZATION employees, salaries and bonuses for their work at the ORGANIZATION.

[snip]

11. Defendants CONCORD MANAGEMENT AND CONSULTING LLC (Конкорд Менеджмент и Консалтинг) and CONCORD CATERING are related Russian entities with various Russian government contracts. CONCORD was the ORGANIZATION’s primary source of funding for its interference operations. CONCORD controlled funding, recommended personnel, and oversaw ORGANIZATION activities through reporting and interaction with ORGANIZATION management.

a. CONCORD funded the ORGANIZATION as part of a larger CONCORD-funded interference operation that it referred to as “Project Lakhta.” Project Lakhta had multiple components, some involving domestic audiences within the Russian Federation and others targeting foreign audiences in various countries, including the United States.

b. By in or around September 2016, the ORGANIZATION’s monthly budget for Project Lakhta submitted to CONCORD exceeded 73 million Russian rubles (over 1,250,000 U.S. dollars), including approximately one million rubles in bonus payments.

c. To conceal its involvement, CONCORD labeled the monies paid to the ORGANIZATION for Project Lakhta as payments related to software support and development. To further conceal the source of funds, CONCORD distributed monies to the ORGANIZATION through approximately fourteen bank accounts held in the names of CONCORD affiliates, including Glavnaya Liniya LLC, Merkuriy LLC, Obshchepit LLC, Potentsial LLC, RSP LLC, ASP LLC, MTTs LLC, Kompleksservis LLC, SPb Kulinariya LLC, Almira LLC, Pishchevik LLC, Galant LLC, Rayteks LLC, and Standart LLC.

Concord was likely included because it tied Prigozhin into the conspiracy, and through him, Vladimir Putin. That tie has been cause for confusion and outright disinformation during the course of the prosecution, as during pretrial motions there were two legal fights over whether DOJ could or needed to say that the Russian state had a role in the operation. Since doing so was never necessary to legally prove the charges, DOJ didn’t fight that issue, which led certain useful idiots to declare, falsely, that DOJ had disclaimed any tie, which is either absurd misunderstanding of how trials work and/or an outright bad faith representation of the abundant public evidence about the ties between Prigozhin and Putin.

By including Concord, the government asserted that it had proof not just that IRA’s use of fake identities had prevented DOJ and the FEC from policing electoral transparency, but also that Putin’s go-to guy in the private sector had used a series of shell companies to fund that effort.

By dropping the charges against the shell companies, that link is partly broken, but the overall ConFraudUS charge (and the charge against Prigozhin) remains, and all but one of the defendants are now biological persons who, if they mounted a defense, would also face criminal penalties that might make prosecution worth it. (I believe the Internet Research Agency has folded as a legal institution, so it would not be able to replay this farce.)

Going to legal war with a shell company

As noted, the indictment included two shell companies — Concord Management and Concord Catering — among the defendants in a period when Russia has increasingly pursued lawfare to try to discredit our judicial system. That’s precisely what happened: Prigozhin hired lawyers who relished trolling the courts to try to make DOJ regret it had charged the case.

As ceded above, DOJ surely didn’t expect that anyone would affirmatively show up to defend against this prosecution. That doesn’t mean they didn’t have the evidence to prove the crimes — both the first level one that bots hid their identities to evade electoral protections, and the second level conspiracy that Prigozhin funded all that through some shell companies. But it likely means DOJ didn’t account for the difficulties of going to legal war against a shell company.

One of the two explanations the government offered for dropping the prosecution admits that the costs of trying a shell company have come to outweigh any judicial benefits.

When defense counsel first appeared on behalf of Concord, counsel stated that they were “authorized” to appear and “to make representations on behalf” of Concord, and that Concord was fully subjecting itself to the Court’s jurisdiction. 5/9/18 Tr. 5 (ECF No. 9). Though skeptical of Concord’s (but not counsel’s) asserted commitments at the initial appearance, the government has proceeded in good faith—expending the resources of the Department of Justice and other government agencies; incurring the costs of disclosing sensitive non-public information in discovery that has gone to Russia; and, importantly, causing the Court to expend significant resources in resolving dozens of often-complex motions and otherwise ensuring that the litigation has proceeded fairly and efficiently. Throughout, the government’s intent has been to prosecute this matter consistent with the interests of justice. As this case has proceeded, however, it has become increasingly apparent to the government that Concord seeks to selectively enjoy the benefits of the American criminal process without subjecting itself to the concomitant obligations.

From the start, there were ongoing disputes about whether the shell company Concord Management was really showing up to defend against this conspiracy charge. On May 5, 2018, DOJ filed a motion aiming to make sure that — given the uncertainty that Concord had been properly served with a summons, since, “Acceptance of service is ordinarily an indispensable precondition providing assurance that a defendant will submit to the jurisdiction of the court, obey its orders, and comply with any judgment.” Concord’s lawyers responded by complaining that DOJ was stalling on extensive discovery requests Concord made immediately.

Next, an extended and recurrent fight over a protective order for discovery broke out. Prigozhin was personally charged in the indictment along with his shell company. The government tried to prevent defense attorneys from sharing discovery deemed “sensitive” with officers of Concord (Prighozhin formally made himself an officer just before this effort started) who were also defendants without prior approval or at least a requirement such access to take place in the United States, accompanied by a defense attorney lawyer. That fight evolved to include a dispute about whether “sensitive” discovery was limited to just Personally Identifiable Information or included law enforcement sensitive information, too (unsurprisingly, Concord said it only wanted the latter and even demanded that DOJ sift out the former). The two sides established a protective order at start. But in December, after the government had delivered 4 million documents, of which it deemed 3.2 million “sensitive,” Concord renewed their demand that Prighozhin have access to discovery. They trollishly argued that only Prigozhin could determine whether the proper translation of the phrase “Putin’s chef” meant he was the guy who cooked for Putin or actually Putin’s boss. At this point, the US started filing sealed motions opposing the discovery effort, but did not yet resort to the Classified Information Procedures Act, meaning they still seemed to believe they could prove this case with unclassified, albeit sensitive, evidence.

Shortly thereafter, DOJ revealed that nothing had changed to alter the terms of the original protective order, and in the interim, some of the non-sensitive discovery (that is, the stuff that could be shared with Prigozhn) had been altered and used in a disinformation campaign.

The subsequent investigation has revealed that certain non-sensitive discovery materials in the defense’s possession appear to have been altered and disseminated as part of a disinformation campaign aimed (apparently) at discrediting ongoing investigations into Russian interference in the U.S. political system. These facts establish a use of the non-sensitive discovery in this case in a manner inconsistent with the terms of the protective order and demonstrate the risks of permitting sensitive discovery to reside outside the confines of the United States.

With a biological defendant, such a stunt might have gotten the defendant thrown in jail (and arguably, this is one of two moments when Judge Dabney Friedrich should have considered a more forceful response to defiance of her authority). Here, though, the prosecution just chugged along.

Perhaps the best proof that Prigozhin was using Concord’s defense as an intelligence-collecting effort came when, late last year, Concord demanded all the underlying materials behind Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control decision to sanction Prigozhin and his companies. As Friedrich noted in her short notation denying the request, OFAC’s decision to sanction Prigozhin had nothing to do with the criminal charges against Concord. Nevertheless, Prigozhin used the indictment of his shell companies in an attempt to obtain classified information on the decision leading to sanctions being imposed on him.

Prigozhin’s goal of using his defense as a means of learning the US government’s sources and methods was clear from the first discovery request. That — and his unwavering efforts to continue the trolling operations — likely significantly influenced the later classification determination that contributed to DOJ dropping the case.

The government intended to try this case with unclassified information

That’s the other cited reason the government dismissed this case: because a classification determination made some of the evidence collected during the investigation unavailable as unclassified information.

[A]s described in greater detail in the classified addendum to this motion, a classification determination bearing on the evidence the government properly gathered during the investigation, limits the unclassified proof now available to the government at trial. That forces the prosecutors to choose between a materially weaker case and the compromise of classified material.

At the beginning of this case, the government said that all its evidence was unclassified, but that much of it was sensitive, either for law enforcement reasons or the privacy of victims in the case.

As described further in the government’s ex parte affidavit, the discovery in this case contains unclassified but sensitive information that remains relevant to ongoing national security investigations and efforts to protect the integrity of future U.S. elections. At a high level, the sensitive-but-unclassified discovery in this case includes information describing the government’s investigative steps taken to identify foreign parties responsible for interfering in U.S. elections; the techniques used by foreign parties to mask their true identities while conducting operations online; the relationships of charged and uncharged parties to other uncharged foreign entities and governments; the government’s evidence-collection capabilities related to online conduct; and the identities of cooperating individuals and, or companies. Discovery in this case contains sensitive information about investigative techniques and cooperating witnesses that goes well beyond the information that will be disclosed at trial.

Nevertheless, after the very long and serial dispute about how information could be shared with the defendant noted above (especially Prigozhin, as an officer of Concord), later in the process, something either became classified or the government decided they needed to present evidence they hadn’t originally planned on needing.

This is one way, Barr critics suggest, that the Attorney General may have sabotaged the prosecution: by deeming information prosecutors had planned to rely on classified, and therefore making key evidence inaccessible for use at trial.

That’s certainly possible! I don’t rule out any kind of maliciousness on Barr’s part. But I think the available record suggests that the government made a good faith classification decision, possibly in December 2019 or January 2020, that ended up posing new difficulties for proving the case at trial. One possibility is that, in the process of applying a very novel interpretation of FARA to this prosecution, the types of evidence the government needed to rely on may have changed. It’s also possible that Prigozhin’s continued trolling efforts — and maybe even evidence that his trolling operations had integrated lessons learned from discovery to evade detection — made sharing heretofore sensitive unclassified information far more damaging to US national security (raising its classification level).

As discussed below, the record also suggests that the government tried to access some evidence via other means, by subpoenaing it from Concord. But Concord’s ability to defy subpoenas without punishment (which gets back to trying to prosecute a shell company) prevented that approach.

The fight over what criminalizes a troll conspiring to fool DOJ (and FEC)

Over the course of the prosecution, the theory of the ConFraudUS conspiracy either got more detailed (and thereby required more specific kinds of evidence to prove) or changed. That may have contributed to changing evidentiary requirements.

Even as the dispute about whether Concord was really present in the court fighting these charges, Concord’s lawyers challenged the very novel application of FARA by attacking the conspiracy charge against it. This is precisely what you’d expect any good defense attorney to do, and our judicial system guarantees any defendant, even obnoxious Russian trolls who refuse to actually show up in court, a vigorous defense, which is one of the risks of indicting foreign corporate persons.

To be clear: the way Concord challenged the conspiracy charge was often frivolous (particularly in the way that Concord’s Reed Smith lawyers, led by Eric Dubelier, argued it). The government can charge a conspiracy under 18 USC § 371 without proving that the defendant violated the underlying crimes the implementation of which the conspiracy thwarted (as Friedrich agreed in one of the rulings on Concord’s efforts). And on one of the charged overt acts — the conspiracy to hide the real purpose of two reconnaissance trips to the US on visa applications — Concord offered only a half-hearted defense; at trial DOJ would likely have easily proven that when IRA employees came to the US in advance of the operation, they lied about the purpose of their travel to get a visa.

That said, while Concord never succeeded in getting the charges against it dismissed, it forced DOJ to clarify (and possibly even alter) its theory of the crime.

That started as part of a motion to dismiss the indictment based on a variety of claims about the application of FARA to conspiracy, arguing in part that DOJ had to allege that Concord willfully failed to comply with FECA and FARA. The government argued that that’s not how a ConFraudUS charge works — that the defendants don’t have to be shown to be guilty of the underlying crimes. Concord replied by claiming that its poor trolls had no knowledge of the government functions that their secrecy thwarted. Friedrich posed two questions about how this worked.

Should the Court assume for purposes of this motion that neither Concord nor its coconspirators had any legal duty to report expenditures or to register as a foreign agent?

Specifically, should the Court assume for purposes of this motion that neither Concord nor its co-conspirators knowingly or unknowingly violated any provision, civil or criminal, of FECA or FARA by failing to report expenditures or by failing to register as a foreign agent?

The government responded by arguing that whether or not the Russian trolls had a legal duty to register, their deception meant that regulatory agencies were still thwarted.

As the government argued in its opposition and at the motions hearing, the Court need not decide whether the defendants had a legal duty to file reports with the FEC or to register under FARA because “the impairment or obstruction of a governmental function contemplated by section 371’s ban on conspiracies to defraud need not involve the violation of a separate statute.” United States v. Rosengarten, 857 F.2d 76, 78 (2d Cir. 1988); Dkt. No. 56, at 9-13. Moreover, the indictment alleges numerous coordinated, structured, and organized acts of deception in addition to the failure to report under FECA or to register under FARA, including the use of false social media accounts, Dkt. No. 1 ¶¶ 32-34, 36, the creation and use of U.S.- based virtual computer infrastructure to “mask[] the Russian origin and control” of those false online identities, id. ¶¶ 5, 39, and the use of email accounts under false names, id. ¶ 40. The indictment alleges that a purpose of these manifold acts of deception was to frustrate the lawful government functions of the United States. Id. ¶ 9; see also id. ¶ 5 (alleging that U.S.-based computer infrastructure was used “to avoid detection by U.S. regulators and law enforcement”); id. ¶ 58 (alleging later obstructive acts that reflect knowledge of U.S. regulation of conspirators’ conduct). Those allegations are sufficient to support the charge of conspiracy to defraud the United States regardless of whether the defendants agreed to engage in conduct that violated FECA or FARA because the “defraud clause does not depend on allegations of other offenses.”

Friedrich ruled against the trolls, except in doing so stated strongly that the government had conceded that they had to have been acting to impair lawful government functions, though not which specific relevant laws were at issue.

Although the § 371 conspiracy alleged does not require willfulness, the parties’ disagreement may be narrower than it first appears. The government concedes that § 371 requires the specific intent to carry out the unlawful object of the agreement—in this case, the obstruction of lawful government functions. Gov’t’s Opp’n at 16 (“Because Concord is charged with conspiring to defraud the United States, . . . the requisite mental state is the intent of impairing, obstructing, or defeating the lawful function of any department of government through deception.” (internal quotation marks omitted)). Further, the government agrees that to form the intent to impair or obstruct a government function, one must first be aware of that function. See Hr’g Tr. at 40 (“[Y]ou can’t act with an intent to impair a lawful government function if you don’t know about the lawful government function.”). Thus, Concord is correct—and the government does not dispute—that the government “must, at a minimum, show that Concord knew what ‘lawful governmental functions’ it was allegedly impeding or obstructing.” Def.’s Mot. to Dismiss at 22; Def.’s Reply at 5. Here, as alleged in the indictment, the government must show that Concord knew that it was impairing the “lawful functions” of the FEC, DOJ, or DOS “in administering federal requirements for disclosure of foreign involvement in certain domestic activities.” Indictment ¶ 9. But Concord goes too far in asserting that the Special Counsel must also show that Concord knew with specificity “how the relevant laws described those functions.” Def.’s Mot. to Dismiss at 22; Def.’s Reply at 5. A general knowledge that U.S. agencies are tasked with collecting the kinds of information the defendants agreed to withhold and conceal would suffice.

Then Concord shifted its efforts with a demand for a Bill of Particulars. The demand itself — and the government’s opposition — included a demand for information about co-conspirators and VPNs, yet another attempt to get intelligence rather than discovery. But Friedrich granted the motion with respect to the application of FECA and FARA.

In other words, it will be difficult for the government to establish that the defendants intended to use deceptive tactics to conceal their Russian identities and affiliations from the United States if the defendants had no duty to disclose that information to the United States in the first place. For that reason, the specific laws—and underlying conduct—that triggered such a duty are critical for Concord to know well in advance of trial so it can prepare its defense.

The indictment alleges that the defendants agreed to a course of conduct that would violate FECA’s and FARA’s disclosure requirements, see Indictment ¶¶ 7, 25–26, 48, 51, and provides specific examples of the kinds of expenditures and activities that required disclosure, see id. ¶¶ 48– 57. Concord, 347 F. Supp. 3d at 50. But the indictment does not cite the specific statutory and regulatory disclosure requirements that the defendants violated. Nor does it clearly identify which expenditures and activities violated which disclosure requirements. Accordingly, the Court will order the government to:

- Identify any statutory or regulatory disclosure requirements whose administration the defendants allegedly conspired to impair, along with supporting citations to the U.S. Code, Code of Federal Regulations, or comparable authority.

- With respect to FECA, identify each category of expenditures that the government intends to establish required disclosure to the FEC. See, e.g., Indictment ¶ 48 (alleging that the defendants or their co-conspirators “produce[d], purchase[d], and post[ed] advertisements on U.S. social media and other online sites expressly advocating for the election of then-candidate Trump or expressly opposing Clinton”) (emphasis added)). The government must also identify for each category of expenditures which disclosure provisions the defendants or their co-conspirators allegedly violated.

- With respect to FARA, identify each category of activities that the government intends to establish triggered a duty to register as a foreign agent under FARA. See, e.g., id. ¶ 48 (same); id. ¶ 51 (alleging that the defendants or their coconspirators “organized and coordinated political rallies in the United States” (emphasis added)). The government must also identify for each category of activities which disclosure provisions the defendants or their co-conspirators allegedly violated.

In a supplemental motion for a bill of particulars, Concord asked which defendants were obliged to file with DOJ and FEC.

That came to a head last fall. In a September 16, 2019 hearing, both sides and Friedrich discussed at length precisely what the legal theory behind the conspiracy was. On Friedrich’s order, the government provided Concord a list of people (whose names were redacted) that,

the defendants conspired to cause some or all of the following individuals or organizations to act as agents of a foreign principal while concealing from those individuals that they were acting as agents of a foreign principal [who should register under FARA].

That is, whether or not this was the original theory of the case, by last fall the government made it clear that it wasn’t (just) Prigozhin or his trolls who needed to register; rather, it was (also) the Americans who were duped into acting and spending money on their behalf. But because they didn’t know they were working on behalf of a foreign principal, they did not register.

Meanwhile, in a motion for clarification, the government argued that it had always intended to include foreigners spending money in the indictment. Friedrich held that that had not actually been included in the original indictment.

These two issues — the claim that duped Americans would have had to register if they knew they were working with a foreign agent, and the need to strengthen the assertion about foreign campaign expenditures — forced the government to go back and supersede the original indictment.

DOJ obtains a superseding indictment with more specific (and potentially new) theories of the case

On November 8, 2019, the government obtained a superseding indictment to include language about foreign donations that Friedrich had ruled was not in the original indictment and language covering the duped Americans who had unknowingly acted as agents of Russian trolls.

New language in the superseding indictment provided more detail of reporting requirements.

¶1 U.S. law also requires reporting of certain election-related expenditures to the Federal Election Commission.

[snip]

U.S. also imposes an ongoing requirement for such foreign agents to register with the Attorney General.

The paragraph explaining the means of the ConFraudUS added detail about what FEC, DOJ, and State functions the trolls’ deceit had thwarted.

¶7 In order to carry out their activities to interfere in the U.S. political and electoral processes without detection of their Russian affiliation, Defendants conspired to obstruct through fraud and deceit lawful functions of the United States government in monitoring, regulating, and enforcing laws concerning foreign influence on and involvement in U.S. elections and the U.S. political system. These functions include (a) the enforcement of the statutory prohibition on certain election-related expenditures by foreign nationals; (b) the enforcement of the statutory requirements for filing reports in connection with certain election-related expenditures; (c) the enforcement of the statutory ban on acting as an unregistered agent of a foreign principal in the United States; (d) the enforcement of the statutory requirements for registration as an agent of a foreign principal (e) the enforcement of the requirement that foreign national seeking entry into the United States provide truthful and accurate information to the government. The defendants conspired to do so by obtaining visas through false and fraudulent statements, camouflaging their activities by foreign nationals as being conducted by U.S. persons, making unlawful expenditures and failing to report expenditures in connection with the 2016 U.S. presidential election, and failing to register as foreign agents carrying out political activities within the United States, and by causing others to take these actions.

These allegations were repeated in ¶9 in the section laying out the ConFraudUs count.

The superseding indictment added a section describing what FEC and DOJ do.

¶25 One of the lawful functions of the Federal Election Commission is to monitor and enforce this prohibition. FECA also requires that individuals or entities who make certain independent expenditures in federal elections report those expenditures to the Federal Election Commission. Another lawful government function of the Federal Election Commission is to monitor and enforce this reporting requirement.

[snip]

¶26 The U.S. Department of Justice enforces the Foreign Agent Registration Act (“FARA”), which makes it illegal to act in the United States as an “agent of a foreign principal,” as defined at Title 22, United States Code, Section 661(c), without following certain registration, reporting, and disclosure requirements established by the Act. Under FARA, the term “foreign principal” includes foreign non-government individuals and entities. FARA requires, among other things, that persons subject to its requirements submit periodic registration statements containing truthful information about their activities and income earned from them. One of the lawful government functions of the Department of Justice is to monitor and enforce this registration, reporting, and disclosure regime.

In perhaps the most interesting addition, the superseding indictment also added language to include the actions of unwitting Americans.

¶48 …and caused unwitting persons to produce, purchase, and post advertisements on U.S. social media and other online sites expressly advocating for the election of then-candidate Trump or expressly opposing Clinton. Defendants and their co-conspirators did not report these expenditures to the Federal Election Commission, or register as foreign agents with the U.S. Department of Justice, nor did any of the unwitting persons they caused to engage in such activities.

The superseding indictment repeated this “unwitting” language in ¶51.

This superseding indictment is significant for two reasons, given the dismissal of the count against the two Concord defendants. First, the possibly changed theory of the conspiracy may have changed what evidence the government needed to prove the crime. For example, it may be that DOJ has evidence of IRA employees acknowledging, for the period of this indictment, that spending money on these activities was illegal, whether or not they knew they had to report such expenditures. It may be that DOJ has evidence of communications between the trolls and actual Americans they otherwise wouldn’t have had to rely on. It may be that DOJ has evidence about the regulatory knowledge of those same Americans about their own reporting obligations. Some of this evidence might well be classified.

Just as importantly, if Bill Barr wanted to jettison this prosecution, he could have done so last November by refusing to permit the superseding indictment. That likely would have undermined the case just as surely (and might have led Friedrich to dismiss it herself), and would have been far better for Trump’s messaging. Moreover, from that point in time, it would have been clear that trial might introduce evidence of how three Trump campaign officials coordinated (unknowingly) with the Russian trolls, something bound to embarrass Trump even if it posed no legal hazard. If Barr had wanted to undermine the prosecution to benefit Trump, November would have been the optimal time to do that, not February and March.

While it’s not clear whether this superseding indictment changed certain evidentiary challenges or not, three key strands of activity that seem to have resulted in the dismissal started only after the superseding: an effort to authenticate digital evidence on social media activity, an effort to subpoena some of that same evidence, and the CIPA process to try to substitute for classified information.

The government goes to some lengths to try to pre-approve normally routine evidence

The last of those efforts, chronologically, may hint at some of the evidentiary issues that led DOJ to drop the case.

In a motion submitted on February 17, the government sought to admit a great deal of the social media and related forensic data in the case. In many trials, this kind of evidence is stipulated into evidence, but here, Concord had been making it clear it would challenge the evidence at trial. So the government submitted a motion in limine to try to make sure it could get that evidence admitted in advance.

Among the issues raised in the motion was how the government planned to authenticate the IP addresses that tied the IRA trolls to specific Facebook and Twitter accounts and other members of the conspiracy (Prigozhin, Concord, and the interim shell companies) to each other. The government redacted significant sections of the filing describing how it intended to authenticate these ties (see, for example, the redaction on page 8, which by reference must discuss subscriber information and IP addresses, and footnote 7 on page 9, the redaction pertaining to how they were going to authenticate emails on page 16, the very long redaction on how they would authenticate emails between IRA and Concord starting on page 17, and the very long redaction on how they were going to authenticate Prigozhin to the IRA starting on page 21).

Concord got special permission to write an overly long 56-page response. Some of it makes it clear they’re undermining the government’s efforts to assert just that, for example on IP addresses.

IP addresses, subscriber information, and cookie data are not self-authenticating. The first link in the government’s authentication argument is that IP addresses,6 subscriber information, and cookie data are self-authenticating business records under Rules 803(6) and 902(11). But the cases the government cites are easily distinguishable and undercut its argument.

6 The IP addresses do not link an account to a specific location or fixed address. For example, for the Russian IP addresses the government indicates that they were somewhere within the city of St. Petersburg, Russia.

[snip]

It should come as no surprise then, given the lack of reliability and untrustworthiness in social media evidence such as that the government seeks to introduce, that the case law forecloses the government’s facile effort at authentication of content here. Unlike Browne, Lewisbey, and the other cases cited above, the government has offered no social media accounts bearing the name of any alleged conspirator and no pictures appearing to be a conspirator adorning such page.7 Nor has the government pointed to a single witness who can testify that she saw a conspirator sign up for the various social media accounts or send an email, or who can describe patterns of consistency across the various digital communications to indicate they come from the same source.

7 The government has indicated to Concord that it intends to introduce at trial Fed. R. Evid. 1006 summaries of IP address records, apparently to create the link between the social media accounts and IRA that is not addressed in the motion. See Ex. B, Jan. 6, 2020 letter. Despite repeated requests from undersigned counsel, the government has identified the 40 social media accounts for it intends to summarize but has not provided the summaries or indicated when it will do so.

Some of this is obviously bullshit, particularly given the government’s contention, elsewhere, that Concord (or IRA, if it was a typo) had dedicated IP addresses. Mostly, though, it appears to have been an attempt to put sand in the wheels of normal criminal prosecution by challenging stuff that is normally routine. That doesn’t mean it’s improper, from a defense standpoint. But given how often DOJ’s nation-state indictments rely on such forensic evidence, it’s a warning about potential pitfalls to them.

The government resorts to CIPA

Even while the government had originally set out to prove this case using only unclassified information, late in the process, it decided it needed to use the Classified Information Procedures Act. That process is where one would look for any evidence that Barr sabotaged the prosecution by classifying necessary evidence (though normally the approval for CIPA could come from Assistant Attorney General for National Security Division John Demers, who is not the hack that Barr is).

In October 2019, Friedrich had imposed a deadline for CIPA if the government were going to use it, of January 20, 2020.

On December 17, the government asked for a two week delay, “to ensure appropriate coordination within the Executive Branch that must occur prior to the filing of the motion,” a request Friedrich denied (even though Concord did not oppose it). This was likely when the classification determination referenced in the motion to withdraw was debated, given that such determinations would dictate what prosecutors had to do via CIPA.

On January 10, 2020, the government filed its first motion under CIPA Section 4, asking to substitute classified information for discovery and use at trial. According to the docket, Friedrich discussed CIPA issues at a hearing on January 24. Then on January 29 and February 10, she posted classified orders to the court security officer, presumably as part of the CIPA discussion.

On February 13, the government asked for and obtained a one-day extension to file a follow-up CIPA filing, from February 17 to February 18, “to complete necessary consultation within the Executive Branch regarding the filing and to ensure proper supervisory review.” If Barr intervened on classification issues, that’s almost certainly when he did, because this happened days after Barr intervened on February 11 in Roger Stone’s sentencing and after Jonathan Kravis, who had been one of the lead prosecutors in this case as well, quit in protest over Barr’s Stone intervention. At the very least, in the wake of that fiasco, Timothy Shea made damn sure he ran his decision by Barr. But the phrase, “consultation within the Executive Branch,” certainly entertains consultation with whatever agency owned the classified information prosecutors were deciding whether they could declassify (and parallels the language used in the earlier request for a filing extension). And Adam Jed, who had been part of the Mueller team, was added to the team not long before this and remained on it through the dismissal, suggesting nothing akin to what happened with Stone happened here.

The government submitted its CIPA filing on the new deadline of February 18, Friedrich issued an order the next day, the government filed another CIPA filing on February 20, Friedrich issued another order on February 28.

Under CIPA, if a judge rules that evidence cannot be substituted, the government can either choose not to use that evidence in trial or drop the prosecution. It’s likely that Friedrich ruled that, if the government wanted to use the evidence in question, they had to disclose it to Concord, including Prigozhin, and at trial. In other words, that decision — and the two earlier consultations (from December to early January, and then again in mid-February) within the Executive Branch — are likely where classification issues helped sink the prosecution.

It’s certainly possible Bill Barr had a key role in that. But there’s no explicit evidence of it. And there’s abundant reason to believe that Prigozhin’s extensive efforts to use the prosecution as an intelligence-gathering exercise both for ongoing disinformation efforts and to optimize ongoing trolling efforts was a more important consideration. Barr may be an asshole, but there’s no evidence in the public record to think that in this case, Prigozhin wasn’t the key asshole behind a decision.

DOJ attempts to treat Concord as a legit party to the court’s authority

Even before that CIPA process started playing out, beginning on December 3, the government pursued an ultimately unsuccessful effort to subpoena Concord. This may have been an attempt to obtain via other means evidence that either had been obtained using means that DOJ had since decided to classify or the routine authentication of which Concord planned to challenge.

DOJ asked to subpoena a number of things that would provide details of how Concord and Prigozhin personally interacted with the trolls. Among other requests, the government asked to subpoena Concord for the IP addresses it used during the period of the indictment (precisely the kind of evidence that Concord would later challenge).

3. Documents sufficient to identify any Internet Protocol address used by Concord Management and Consulting LLC from January 1, 2014 to February 1, 2018.

Concord responded with a load of absolute bullshit about why, under Russian law, Concord could not comply with a subpoena. Judge Friedrich granted the some of the government’s request (including for IP addresses), but directed the government to more narrowly tailor its other subpoena requests.

On December 20, the government renewed its request for other materials, providing some evidence of why it was sure Concord had responsive materials. Concord quickly objected again, again wailing mightily. In its reply, the government reminded Friedrich that she had the ability to order Concord to comply with the subpoena — and indeed, had gotten Concord’s assurances it would comply with orders of the court when it first decided to defend against the charges. It even included a declaration from an expert on Russian law, Paul Stephan, debunking many of the claims Concord had made about Russian law. Concord wailed, again. On January 24, Friedrich approved the 3 categories of the subpoena she had already approved. On January 29, the government tried again, narrowing the request even to — in one example — specific days.

Calendar entries reflecting meetings between Prigozhin and “Misha Lakhta” on or about January 27, 2016, February 1, 2016, February 2, 2016, February 14, 2016, February 23, 2016, February 29, 2016, May 22, 2016, May 23, 2016, May 28, 2016, May 29, 2016, June 7, 2016, June 27, 2016, July 1, 2016, September 22, 2016, October 5, 2016, October 23, 2016, October 30, 2016, November 6, 2016, November 13, 2016, November 26, 2016, December 3, 2016, December 5, 2016, December 29, 2016, January 19, 2017, and February 1, 2017.

Vast swaths of the motion (and five exhibits) explaining why the government was sure that Concord had the requested records are sealed. Concord responded, wailing less, but providing a helpful geography lesson to offer some alternative explanation for the moniker “Lakhta,” which the government has long claimed was the global term for Prigozhin’s information war against the US and other countries.

But the government fails to inform the Court that “Lakhta” actually means a multitude of other things, including: Lake Lakhta, a lake in the St. Petersburg area, and Lakhta Center, the tallest building in Europe, which is located in an area within St. Petersburg called the Lakhta-Olgino Municipal Okrug.

On February 7, Friedrich largely granted the government’s subpoena request, approving subpoenas to get communications involving Prigozhin and alleged co-conspirators, as well as records of payments and emails discussing them. That same day and again on February 21, Concord claimed that it had communicated with the government with regards to the subpoenas, but what would soon be clear was non-responsive.

On February 27, the government moved to show cause for why Concord should not be held in contempt for blowing off the subpoenas, including the request for IP addresses and the entirety of the second subpoena (for meetings involving Prigozhin and records of payments to IRA). Concord wailed in response. The government responded by summarizing Concord’s response:

Concord’s 18-page pleading can be distilled to three material points: Concord’s attorneys will not make any representations about compliance; Concord will not otherwise make any representations about compliance; and Concord will not comply with a court order to send a representative to answer for its production. The Court should therefore enter a contempt order and impose an appropriate sanction to compel compliance.

Friedrich issued an order that subpoena really does mean subpoena, demanding some kind of representation from Concord explaining its compliance. In response, Prigozhin sent a declaration partly stating that his businesses had deleted all available records, partly disclaiming an ability to comply because he had played games with corporate structure.

With respect to category one in the February 10, 2020 trial subpoena, Concord never had any calendar entries for me during the period before I became General Director, and I became General Director after February 1, 2018, so no searches were able to be performed in Concord’s documents. Concord did not and does not have access to the previous General Director’s telephone from which the prosecution claims to have obtained photographs of calendars and other documents, so Concord is unable to confirm the origin of such photographs.

He claimed to be unable to comply with the request for IP addresses because his contractors “cannot” provide them.

In order to comply with category three in the trial subpoena dated January 24, 2020, in Concord’s records I found contracts between Concord and Severen-Telecom JSC and Unitel LLC, the two internet service providers with which Concord contracted between January 1, 2014 and February 1, 2018. Because these contracts do not identify the internet protocol (“IP”) addresses used by Concord during that period, on January 7, 2020 I sent letters on behalf of Concord to Severen-Telecom JSC and Unitel LLC transmitting copies of these contracts and requesting that the companies advise as to which IP addresses were provided to or used by Concord during that period. Copies of these letters and English translations, as well as the attached contracts, are attached as Exhibits 2 and 3. Severen-Telecom JSC responded in writing that the requested information cannot be provided. A copy of Severen-Telecom JSC’s letter and an English translation are attached as Exhibit 2. Unitel LLC responded that information regarding IP addresses cannot be provided. A copy of Unitel LLC’s letter and an English translation of is attached as Exhibit 3. Accordingly, Concord does not have any documents that could be provided in response to category three (3) of the January 24, 2020 subpoena.

The government responded by pointing out how bogus Prigozhin’s declaration was, not least his insistence that any oligarch like him would really be the person in charge of his companies’ record-keeping. It also described evidence — which is redacted — that Concord had an in-house IT provider at the time (though notes that “as the Court knows, it appears that Concord [sic; this is probably IRA] registered and maintained multiple dedicated IP addresses during the relevant time period”). It further noted that the date that Prigozhin claimed his company started destroying records after 3 months perfectly coincided to cover the start date of this subpoena. In short, it provided fairly compelling evidence that Prigozhin, after agreeing that his company would be subject to the authority of the court when it first filed an appearance in the case, was trolling the court from the safety of Russia.

On March 5, Judge Friedrich nevertheless allowed that bullshit response in her court and declined to hold Concord in contempt. Eleven days later, the government moved to dismiss the case.

The government files the motion to dismiss before the evidentiary dispute finishes but after the subpoena and CIPA fail

On March 16 — 17 days after what appears to be the final CIPA order and 11 days after Friedrich declined to hold Concord or Prigozhin in contempt, and one day before the government was due to file a follow-up to its motion in limine to authenticate normally routine evidence in the case — the government moved to dismiss the case.

While it’s unclear what evidence was deemed to be classified late in the prosecution (likely in December), it seems fairly clear that it affected (and possibly was a source or method used to collect) key forensic proof in the case. It’s also unclear whether an honest response to the government’s trial subpoenas would have replaced that evidence.

What is clear, however, is that there is sufficient explanation in the public record to support the government’s explanation — that Prigozhin was using the prosecution to reap benefits of obtaining information about US government efforts to thwart his activities without risking anything himself. And whether or not the government would be able to prove its case with the classification and CIPA decisions reflected in the docket, the trial itself would shift more evidence into the category of information that would get shared with Prigozhin.

None of that disproves that Barr sabotaged the case. But it does provide sufficient evidence to explain why DOJ dismissed the case, without assuming that Barr sabotaged it.

Other cases of interest

As noted above, not only do the identity theft related charges remain, but so does the ConFraudUS case for all the biological defendants, including Prigozhin. It may be that, given the opportunity to imprison Prigozhin in the highly unlikely event that he ever showed up in the US for trial, the classification trade-offs would be very different.

But there are three other legal issues of interest, given this outcome.

First, there’s one more unsurprising detail about the superseding indictment: It also included an end-date, January 2018. That’s not surprising because adding later activities probably would presented all sorts of problems given how advanced the trial was last November. But it’s also significant because it means double jeopardy would not attach for later activities. So the government could, if the calculus on classification ever changed, simply charge all the things Prigozhin and his trolls have been doing since January 2018 in an indictment charged under its revised theory.

That’s particularly significant given that, in September 2018, prosecutors in EDVA charged Prigozhin’s accountant, Elena Alekseevna Khusyaynova. Even at the time, I imagined it might be a vehicle to move the IRA prosecution if anything happened to it in DC. Unsurprisingly, given that she’s the accountant at the center of all this, the Khusyaynova complaint focused more closely on the money laundering part of the prosecution. Plus, that complaint incorporated evidence of Prigozhin’s trolls reveling in their own indictment, providing easy proof of knowledge of the legal claims DOJ made that didn’t exist for the earlier indictment. None of that would change the calculus around classified evidence (indeed, some of the overt acts described in the Khusyaynova complaint seem like the kind of evidence that Prigozhin would have turned over had he complied with the Concord subpoena. So there is another vehicle for such a prosecution, if DOJ wanted to pursue it.

Finally, Prigozhin has not succeeded with all his attempts to wage lawfare in support of his disinformation efforts. In January, he lost his bid to force Facebook to reinstate his fake news site, Federal Agency of News, based off an argument that because Facebook worked so closely with the government, it cannot exercise its own discretion on its private site. As I laid out here, the suit intersected with both the IRA indictment and Khusyaynova complaint, and engaged in similar kinds of corporate laundry and trollish bullshit. The decision was a no-brainer decision based on Section 230 grounds, giving providers immunity when they boot entities from their services. But the decision also confirms what is already evident: when it comes to shell companies in the business of trolling, thus far whack-a-mole removals have worked more consistently than seemingly symbolic prosecution.

DOJ may well revisit how it charged this to try to attach a FARA liability onto online disinformation. But ultimately the biological humans, not the corporation shells or the bots, need to be targeted.