John Durham’s Disinformation Problem

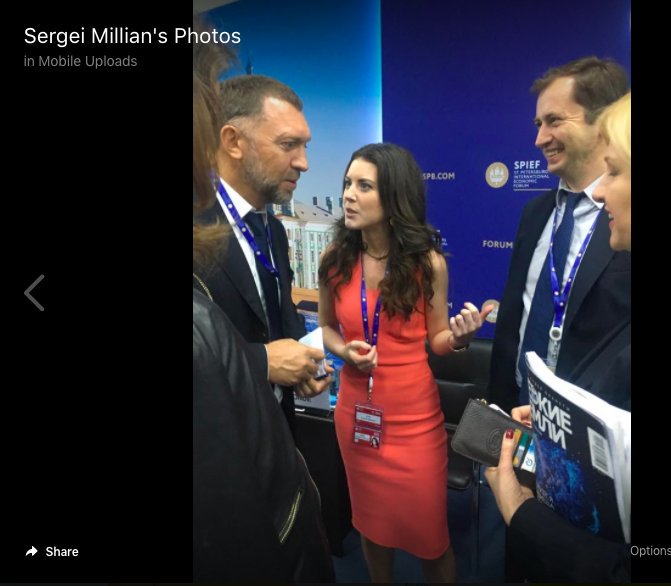

The only person about whose ties to Christopher Steele John Durham showed no curiosity was Oleg Deripaska.

The only person whose ties to the creator of the dossier that led the FBI to adopt false claims against Trump aides that Durham didn’t pursue was the guy, on whose behalf, Trump’s campaign regularly sent out internal polling data starting in May 2016, the guy, on whose behalf, Trump’s campaign manager briefed Russian agent Konstantin Kilimnik on the campaign’s plan to win swing states. The 2021 Treasury filing that stated, as fact, that Kilimnik is a, “known Russian Intelligence Services agent implementing influence operations on their behalf,” also stated, as fact, that in 2016, “Kilimnik provided the Russian Intelligence Services with sensitive information on polling and campaign strategy,” the very same polling data and campaign strategy he obtained from Trump’s campaign manager on Oleg Deripaska’s behalf. As I’ve laid out, John Durham never mentioned Kilimnik in his report, not once, to say nothing of how Kilimnik obtained internal polling data and a campaign strategy briefing and delivered it to Russian spies.

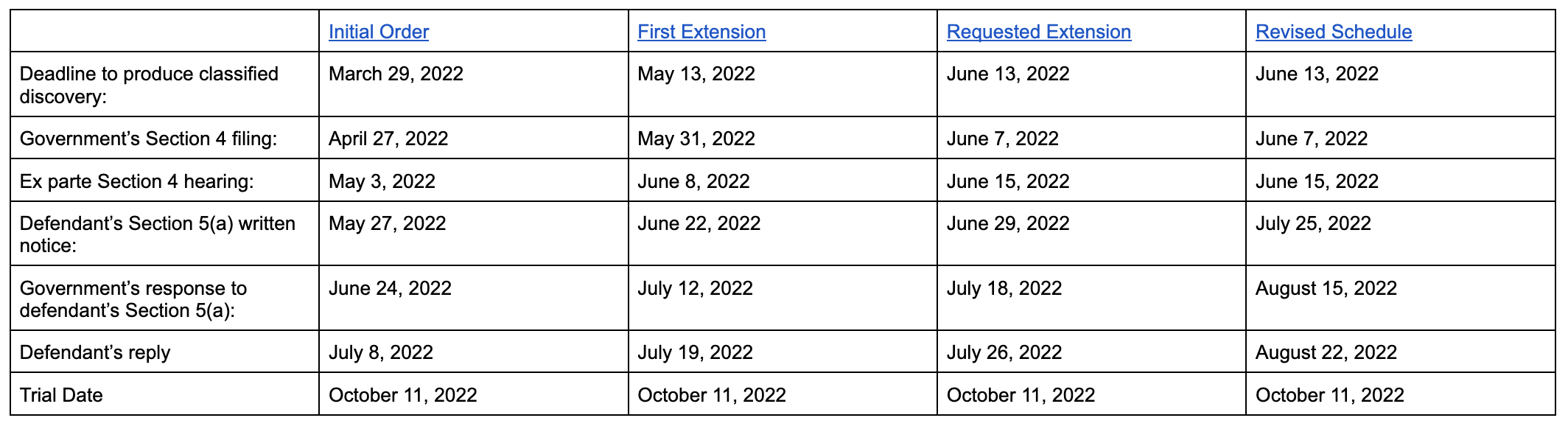

Everyone else who had the least little tie to Christopher Steele, Durham pursued relentlessly. He charged Igor Danchenko, even though the FBI used Danchenko to, “fish information from Mr. Steele about what Mr. Steele was up to,” as the former British spook pursued a second dossier against Trump in 2017. He charged Danchenko even though Danchenko neither wrote the dossier nor shared it (or even knew it was being shared) with the FBI. Durham not only charged Steele’s primary source, but he caused Danchenko to be burned as an FBI informant, even though Danchenko’s subsource network had reportedly proven incredibly valuable to the FBI. Durham even helped to ensure that the FBI would not pay a significant lump sum payment to Danchenko for his assistance after Republicans in Congress led to his exposure.

Durham’s report aired, at length, details of the earlier counterintelligence investigation into Danchenko; he didn’t include the reasons Danchenko’s handler found the allegations unreliable (indeed, an undated referral in his report suggests Durham retaliated against Danchenko’s handler Kevin Helson for providing those details at trial). Once again, Durham failed his own standards of including exculpatory information. Durham also falsely claimed that Danchenko never told the FBI that his source network knew of his tie to Steele. In reality, as I’ll return to below, in his first interview with the FBI, Dancehnko described that two of them did.

Durham also conducted the investigation into Charles Dolan he believed Robert Mueller’s team should have done in 2017. Durham obtained Dolan’s email, his work email, his phone records, and his Facebook records. Durham still found no proof that Dolan was the source for any of the Russia-related reports in the dossier. After not getting the answers he wanted in Dolan’s first interview, Durham made him a subject and had him review an email Dolan sent, passing on information he had read in public sources, with a report in the dossier, which Dolan conceded might have come from his email. But Dolan still testified that Danchenko never asked Dolan for information about Trump’s connection to Russia.

It wasn’t just Danchenko and Dolan, though. A key part of Durham’s conspiracy theory against Michael Sussmann depended on the fact that — shortly after Sussmann got the Alfa Bank anomaly independent of the Hillary campaign — Sussmann asked Steele about the bank during a meeting where Marc Elias asked Sussmann to help vet Steele. Durham tried to introduce Steele’s subsequent report on Alfa Bank based on that meeting, even though all the evidence shows that if the Brit did provide the report to the FBI, he did so on his own, and it’s not even clear that he himself did provide that particular report directly to his FBI handler.

Durham compelled Fusion’s tech expert Laura Seago to testify because a meeting and four emails she exchanged with Rodney Joffe were the one link between Joffe and the dossier. Seago testified that the Alfa Bank allegations were not a big part of the work she did on Trump-related issues.

Durham had Deborah Fine testify because, as one of the Hillary Campaign’s Deputy General Counsels, she was the only person associated with the campaign — aside from Marc Elias — who regularly met with Fusion GPS. Durham made her testify even though she knew nothing about research relating to Alfa Bank and didn’t remember any conversations about Trump and Russia. Instead, Fine testified, her interaction with Fusion pertained to lawsuits filed against Trump, his company, and his family that Fusion helped to research.

Durham used every method at his disposal — including getting Judge Christopher Cooper to override the Hillary campaign’s claim of privilege over some Fusion emails — to unpack any possible relationship that subjects of his investigation had with Christopher Steele.

Except Oleg Deripaska.

In fact, Durham did the opposite: he obscured the import of Deripaska’s ties to Steele.

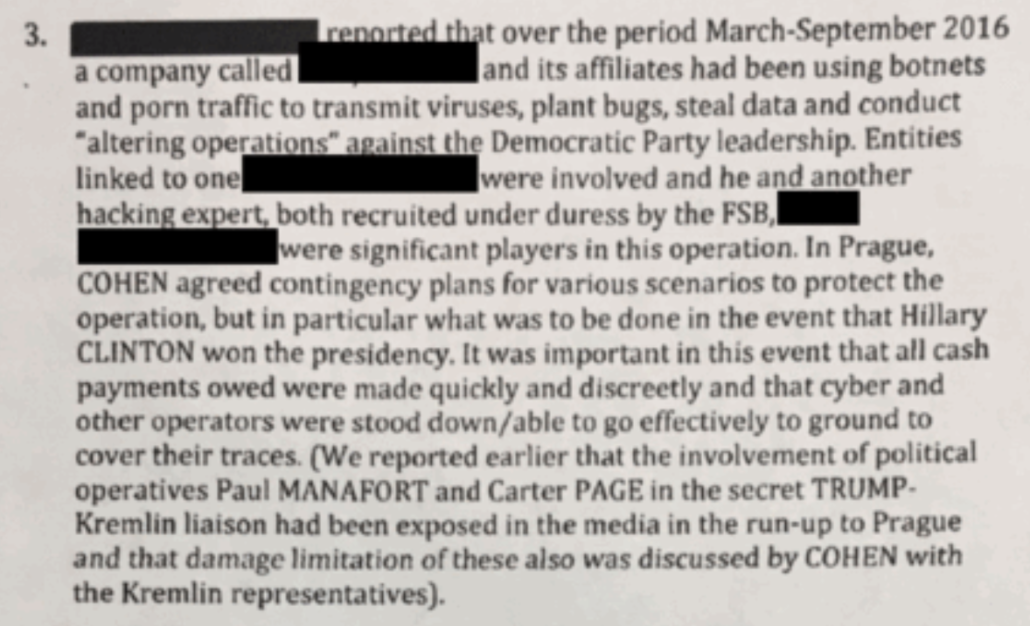

In his report, Durham asserted, as fact, something that had only been implied before: Oleg Deripaska paid Steele in spring 2016 to collect information on Paul Manafort.

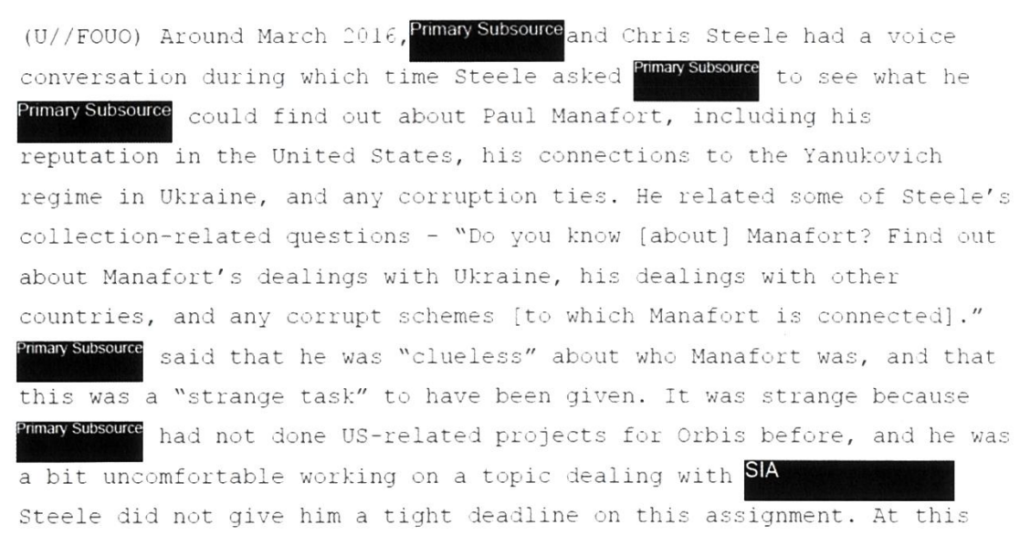

When interviewed by the FBI in September 2017, Steele stated that his initial entree into U.S. election-related material dealt with Paul Manafort’s connections to Russian and Ukrainian oligarchs. In particular, Steele told the FBI that Manafort owed significant money to these oligarchs and several other Russians. 890 At this time, Steele was working for a different client, Russian oligarch Oleg Deripaska, often referred to as “Putin’s Oligarch” in media reporting, on a separate litigation-related issue. 891

In the same way that Paul Singer initiated the open source research into Trump done by Fusion GPS before the Democrats took it over, Oleg Deripaska — the person on whose behalf Russian intelligence obtained inside dirt, via Konstantin Kilimnik, from Trump’s campaign — initiated the HUMINT collection on Trump’s team, lasting at least until April 18, 2016, even after the Russian attack on Hillary Clinton had already started.

Oleg Deripaska started the dossier project and only later did the Democrats pick it up, unwitting to the fact that it was started by a guy who was busy playing a key role in Russia’s influence operation targeting Hillary’s campaign.

It’s bad enough that Durham didn’t pursue the tie between the dossier and Russia’s later efforts to obtain inside dirt from Trump’s campaign.

But when he described the evidence that Russia likely learned of Steele’s work for the DNC by July 2016, before Steele did virtually all but one of the substantive reports on Trump, Durham did so in a section almost 100 pages earlier than his description of Deripaska’s ties to Steele, and by adopting the moniker the DOJ IG Report used for Deripaska, “Oligarch 1,” he hid that the source of that knowledge was Deripaska himself.

As the record now reflects, at the time of the opening of Crossfire Hurricane, the FBI did not possess any intelligence showing that anyone associated with the Trump campaign was in contact with Russian intelligence officers at any point during the campaign. 251 Moreover, the now more complete record of facts relevant to the opening of Crossfire Hurricane is illuminating. Indeed, at the time Crossfire Hurricane was opened, the FBI (albeit not the Crossfire Hurricane investigators) was in possession of some of the Steele Reports. However, even if the Crossfire Hurricane investigators were in possession of the Steele Reports earlier, they would not have been aware of the fact that the Russians were cognizant of Steele’s election-related reporting. The SSCI Russia Report notes that”[s]ensitive reporting from June 2017 indicated that a [person affiliated] to Russian Oligarch 1 was [possibly aware] of Steele’s election investigation as of early July 20 l 6.” 252 Indeed, “an early June 2017 USIC report indicated that two persons affiliated with [Russian Intelligence Services] were aware of Steele’s election investigation in early July 2016.”253 Put more pointedly, Russian intelligence knew of Steele’s election investigation for the Clinton campaign by no later than early July 2016. Thus, as discussed in Section IV.D. l .a.3, Steele’s sources may have been compromised by the Russians at a time prior to the creation of the Steele Reports and throughout the FBI’s Crossfire Hurricane investigation.

Steele’s source network may have been compromised before the project started, Durham charged. But Durham hid the evidence that if it was compromised, it was compromised by the guy on whose behalf Trump’s campaign manager shared campaign information with Russian intelligence.

In fact, the DOJ IG Report, finished in December 2019 and from which Durham adopted that moniker, Oligarch 1, strongly suggests that Deripaska himself and his “known Russian Intelligence Services agent implementing influence operations on their behalf” sidekick, Konstantin Kilimnik, were the source of any disinformation in the dossier.

Durham did not pursue that evidence, at all, in his report. As I said, he never once mentioned Kilimnik.

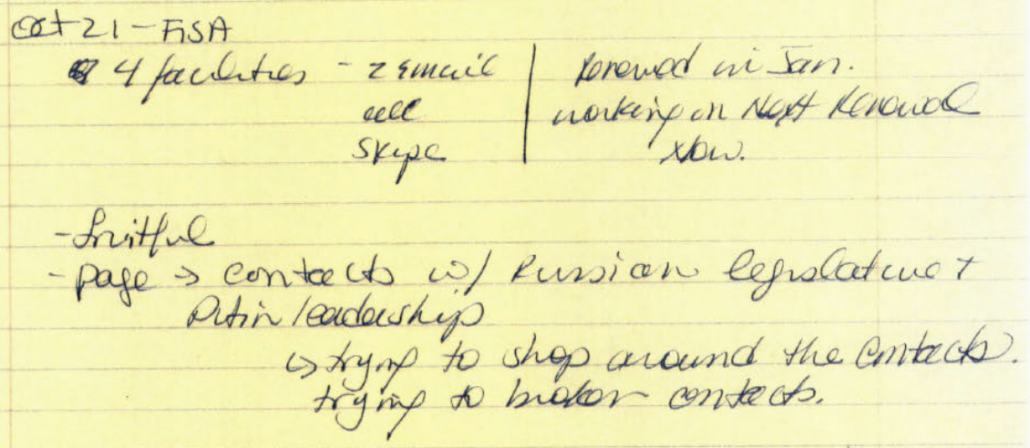

He ignored Deripaska’s likely role in disinformation in 2016, even though he focused repeatedly on disinformation in his report. He complained, for example, that the FBI didn’t unpack any potential disinformation in the dossier before using it in the Carter Page FISA applications.

The failure to identify the primary sub-source early in the investigation’s pursuit of FISA authority prevented the FBI from properly examining the possibility that some or much of the non-open source information contained in Steele’s reporting was Russian disinformation (that wittingly or unwittingly was passed along to Steele), or that the reporting was otherwise not credible.

He suggested Danchenko’s unresolved counterintelligence investigation — and not Oleg Deripaska — was the source of potential disinformation.

Our review found no indication that the Crossfire Hurricane investigators ever attempted to resolve the prior Danchenko espionage matter before opening him as a paid CHS. Moreover, our investigation found no indication that the Crossfire Hurricane investigators disclosed the existence of Danchenko’s unresolved counterintelligence investigation to the Department attorneys who were responsible for drafting the FISA renewal applications targeting Carter Page. As a result, the FISC was never advised of information that very well may have affected the FISC’s view of Steele’s primary sub-source’s (and Steele’s) reliability and trustworthiness. Equally important is the fact that in not resolving Danchenko’s status vis-a-vis the Russian intelligence services, it appears the FBI never gave appropriate consideration to the possibility that the intelligence Danchenko was providing to Steele -which, again, according to Danchenko himself, made up a significant majority of the information in the Steele Dossier reports – was, in whole or in part, Russian disinformation.

He falsely used one answer Danchenko gave in his first meeting with the FBI to suggest that might be a source of disinformation.

Danchenko’s uncharged false statements to the FBI reflecting the fact that he never informed friends, associates, and/or sources that he worked for Orbis or Steele and that “you [the FBI] are the first people he’s told.” In fact, the evidence revealed that Danchenko on multiple occasions communicated and emailed with, among others, Dolan regarding his work for Steele and Orbis, thus potentially opening the door to the receipt and dissemination of Russian disinformation;

The claim was grossly dishonest, because at the same meeting, Danchenko described that Olga Galkina knew he worked in business intelligence, and also revealed how he asked Orbis for help setting up another of his sources with language instruction in the UK. Danchenko told the FBI enough, from his first interview, that gave them reason to think his sources might know for whom he reported. But Durham accused Danchenko of lying about it anyway, because he needed to blame Danchenko, and not Deripaska, for any disinformation in the dossier.

Durham even complained that Peter Strzok had not considered whether the original Australian report about George Papadopoulos could be disinformation. Maybe it’s the Australians’ fault, Durham suggests, not Deripaska’s!

Durham looked for disinformation in every source but the one place where — even by early in his investigation — the FBI already suspected it, in the guy who kicked off the dossier project in 2016, before the Democrats even got to it.

Durham’s treatment of Deripaska’s suspected role in disinformation in 2016 is all the more astounding given how quickly Durham dismissed the possibility that the foundation of his own investigation was disinformation.

Durham built his entire project on a source that the intelligence community warned him might be a fabrication, the Russian intelligence report claiming that Hillary had a plan to hold Trump accountable for his ties to Russia. Durham dismissed that warning in two short paragraphs.

As was declassified and made public previously, the purported Clinton Plan intelligence was derived from insight that “U.S. intelligence agencies obtained into Russian intelligence analysis.” 394 Given the origins of the Clinton Plan intelligence as the product of a foreign adversary, the Office was cognizant of the statement that DNI Ratcliffe made to Senate Judiciary Chairman Lindsey Graham in a September 29, 2020 letter: “The [intelligence community] does not know the accuracy of this allegation or the extent to which the Russian intelligence analysis may reflect exaggeration or fabrication.” 395

Recognizing this uncertainty, the Office nevertheless endeavored to investigate the bases for, and credibility of, this intelligence in order to assess its accuracy and its potential implications for the broader matters within our purview.

Remember: Durham made this report the cornerstone of his investigation starting around February 2020, three months after the DOJ IG Report, in December 2019, publicly gave reason to believe that Deripaska had been feeding the dossier with disinformation starting at least by July 2016, the month of this purported Russian intelligence report. Durham made this report the cornerstone of his investigation in spite of his confirmation that Deripaska initiated the dossier project in March 2016 and continued it until weeks before the Democrats took it over.

And Durham made this report the cornerstone of his investigation by fabricating a claim that even the Russians didn’t make about Hillary: that she wanted to promote a false narrative about Trump, rather than demonstrate all the true and damning Russian ties Trump had that Fusion had already fed to Franklin Foer by early July 2016.

Hillary Clinton had no incentive to pay a lot of money for false information — and nor did anyone need to fabricate Trump’s ties to Russia. Paying for false information predictably could — and did, and hasn’t stopped doing in the interim seven years — backfire stupendously. Plus, as I have shown, paying for false information demonstrably led to complacency about the possibility that the material stolen in the earlier hack would be used later in the campaign.

Hillary Clinton had no incentive to pay for disinformation! And Durham utterly fabricated the claim that she did!

But Oleg Deripaska would have an incentive to pay for disinformation.

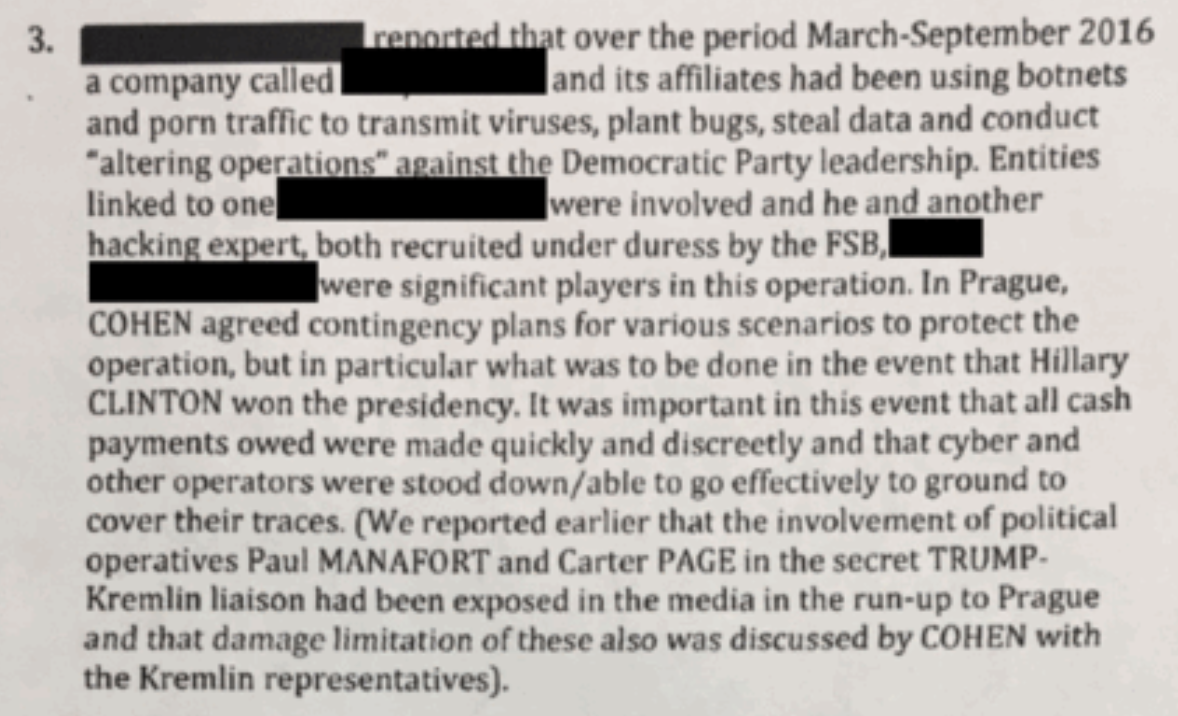

Not only did that false information in the dossier send the FBI looking at Carter Page as Paul Manafort’s liaison with Russia instead of Konstantin Kilimnik — who then waltzed into a cigar bar in New York to hear how Trump planned to win Pennsylvania. Not only did the false information in the dossier lead the FBI to spend valuable time vetting the dossier rather than pursuing the hundreds of real ties Trump had to Russia.

But the false information in the dossier — and the way that Trump, in the wake of a January 2017 Manafort meeting with another Deripaska associate, attacked the dossier as a way to discredit the larger Russian investigation — undermined the investigation and ultimately did untold damage to the FBI.

The false information in the dossier has been one of the most singular sources of partisan antagonism in the United States ever since. It has ripped the country apart. One right wing influencer even blamed the dossier for the January 6 attack on the Capitol.

Hillary Clinton had no incentive to pay for that. But Oleg Deripaska did.

And rather than laying out Deripaska’s likely role in the disinformation in the dossier, the known disinformation behind claims about Trump, Durham simply invented a claim that after such time as Deripaska had kicked off the dossier project and the Democrats picked it up, after such time as Deripaska knew that Democrats were funding the dossier, Hillary decided to make up false claims about Trump.

Rather than honestly laying out the public evidence that Deripaska was playing a ruthless double game — using Steele to make Manafort legally and financially less secure while using Manafort’s insecurity to win his cooperation with the influence operation — Durham did the one thing that could continue the wild success of Deripaska’s disinformation project: Blame Hillary for the disinformation, rather than Deripaska himself.

I don’t know whether Durham wittingly decided he was going to play Oleg Deripaska’s flunkie from inside the federal government (to say nothing of Alfa Bank, with whose investigation Durham shared a script). But everything he did with his investigation, every misrepresentation he makes in his report, all the human carnage Durham has done since, simply continues the disinformation project Deripaska kicked off seven years ago.

And that’s why his singular lack of curiosity about Deripaska’s ties to Steele is so telling.