Former Secret Cooperator Enrique Tarrio Reveals a Secret Cooperation Deal

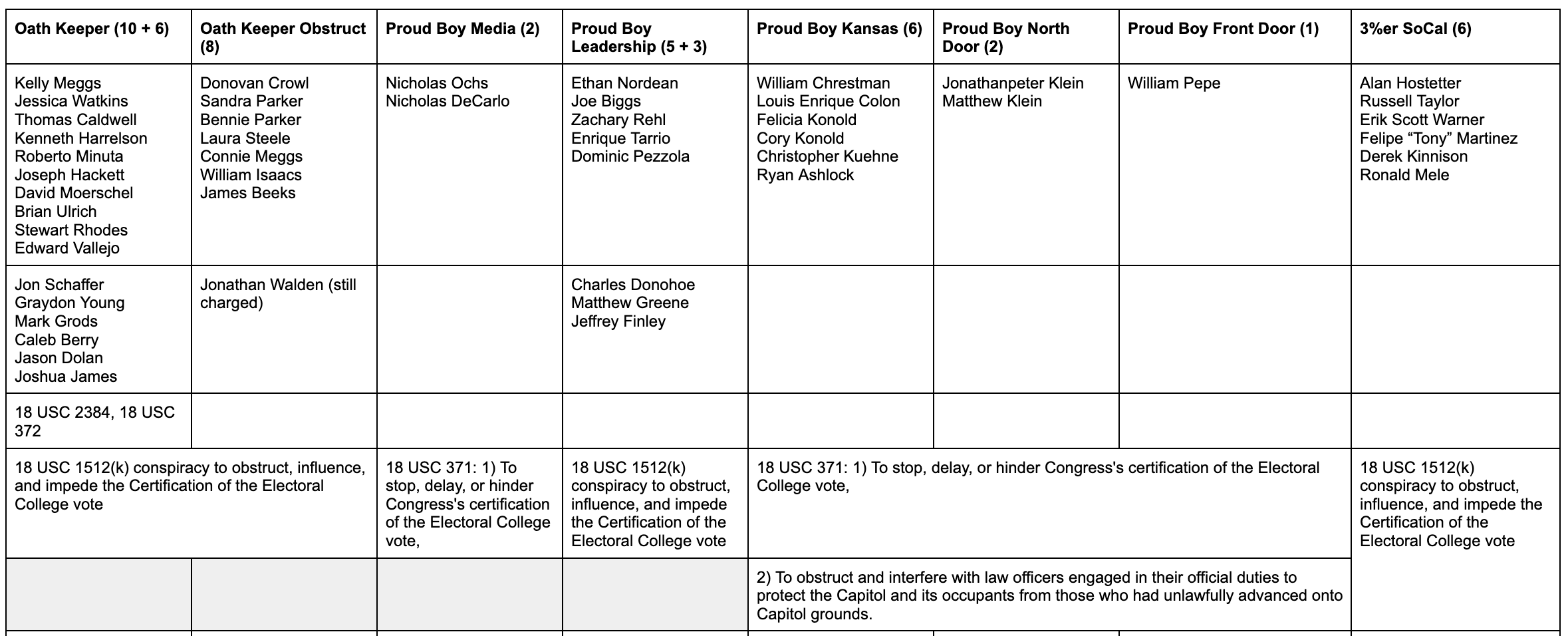

Last Friday, in the guise of arguing that Enrique Tarrio’s trial should be moved from DC to Miami, one of his attorneys, Sabino Jauregui, revealed that DOJ had gotten a plea agreement with Jeremy Bertino and “Stewart” in June, but only rolled them out recently, which he claimed was proof of politicization. That argument, like Jauregui’s arguments that the national media coverage that Tarrio himself had cultivated and a DC lawsuit against the Proud Boys that the judge presiding over the case, Tim Kelly, had never heard of, meant Tarrio could not be tried in DC was nonsensical and probably false as to motive. It was a painfully stupid argument from lawyers from one of the few people who could make a real case for moving his trial (though not to Miami, where there has been localized Proud Boy coverage).

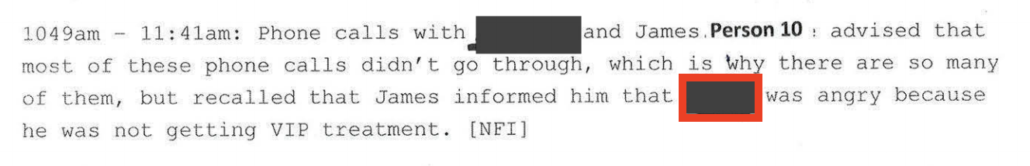

But it revealed that the person identified as “Person Three” in many of the charging documents, John “Blackbeard” Stewart, had entered a plea agreement in June. After I tweeted that out, WaPo described a June 10 Information charging someone with conspiring to obstruct the vote certification.

The disclosure by Tarrio’s defense aligns with court records showing that prosecutors on June 10 charged a defendant who was expected to plead guilty and cooperate with investigators in a case related to Tarrio and four top lieutenants, who stand accused of planning in advance to oppose the lawful transfer of presidential power by force. The unidentified defendant was charged with conspiring to obstruct an official proceeding of Congress, according to the records — initially posted publicly by the court but removed from public view.

It’s unclear whether Jauregui really meant to argue that the non-disclosure of a June plea would harm his client — or even the early October disclosure of a Bertino plea that was signed in September — or whether this was the kind of happy accident that sometimes exposes a detail that might be useful for others. But it reveals that in the same period when DOJ charged Tarrio and his alleged co-conspirators with sedition, DOJ secretly added a cooperator against them.

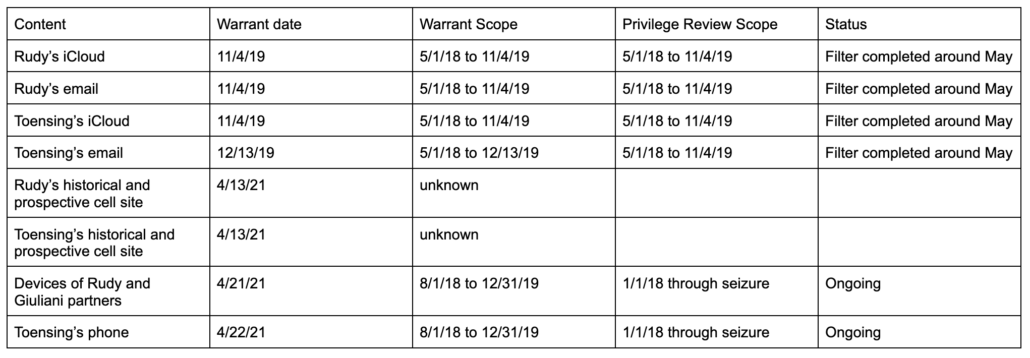

That detail isn’t all that surprising — and it’s certainly not cause to move the trial to Miami. The government often keeps cooperation deals secret — indeed, the government kept at least some of Tarrio’s cooperation secret when he was cooperating against his codefendants and other medical fraudsters in the 2010s. They did so, in part, so he could conduct undercover operations.

But it raises other questions, such as what happened with Aaron Whallon Wolkind, who also figured prominently in charging documents as Person 2, but who was not mentioned in Bertino’s statement of offense. The recent silence about AWW’s role in January 6 is all the more telling given that Zach Rehl’s co-travelers, Isaiah Giddings, Brian Healion, and Freedom Vy just had their pre-indictment prosecution continued until February; along with Rehl, they’re the ones that interacted most closely with AWW on and leading up to January 6. We may learn more by Wednesday, which is the due date for the two sides to submit a new sentencing date for Jeff Finley, another co-traveler of this crowd.

There has long been reason to wonder about what was going on in the Proud Boy case behind the scenes. The revelation of hidden plea deals only confirms that.

The silence of most Oath Keeper cooperators

It’s not just the Proud Boys investigation where there’s uncertainty about cooperating witnesses.

A recent status report for Jon Schaffer, who was generally understood to be a cooperator against the Oath Keepers, reveals that his attorney,

has reached out to counsel for the government, Ahmed Baset, Esq., multiple times in regard to the Joint Statius Report as requested by this Court. Unfortunately, as of the filing of this report, undersigned counsel has not been able to reach Mr. Baset.

The status report includes the same description as used in earlier status reports, one that was always weird in conjunction with the Oath Keepers and now is completely incompatible with it.

Multiple defendants charged in the case in which the Defendant is cooperating have been presented before the Court; several are in the process of exploring case resolutions and a trial date has yet to be set.

That doesn’t rule out that his cooperation was for different militia defendants, or for Oath Keeper James Breheny, whose pre-indictment prosecution was recently continued until January (Breheny is most interesting for an event he attended in Lancaster, PA, not far from both John Stewart and AWW).

The continuing lack of clarity about Schaffer’s cooperation comes even as he has successfully hidden from DC process servers for months. He is one of the cooperators whose plea included the possibility of witness protection, but the process servers attempting to notify him of lawsuits against him seem to be chasing real addresses.

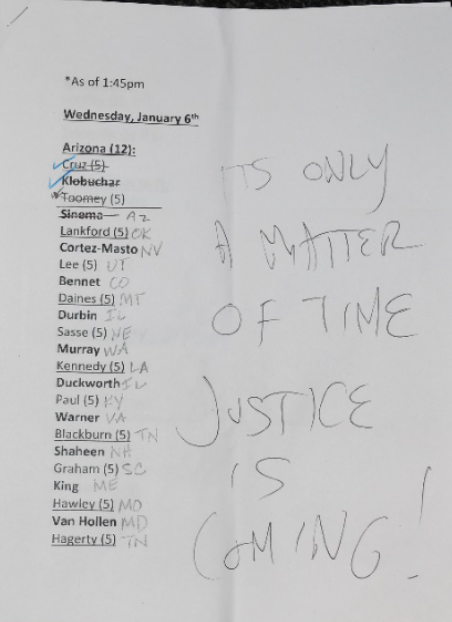

Schaffer aside, there are even interesting questions regarding cooperators in the main Oath Keeper conspiracy. After Graydon Young finished testifying yesterday (revealing, among other things, that he had learned that Kelly Meggs had high level ties to the Proud Boys), prosecutor Jeffrey Nestler revealed there is just one more civilian witness. If by “civilian” he includes cooperators, that means at most one more Oath Keeper cooperator — probably Joshua James, whose cooperation on post-January 6 development seems critical for the sedition charge — will testify. That would mean a bunch of the cooperators — Mark Grods, Caleb Berry, Brian Ulrich, and Todd Wilson — would not have taken the stand (Jason Dolan is the only other cooperator, in addition to Young, who has testified so far). While some of these cooperators were likely important for getting others to flip (for example, Grods would have implicated James), there are others, like Wilson, whose testimony might be uniquely valuable.

Or perhaps in the same way DOJ was attempting to hide at least one Proud Boy cooperator, the Oath Keeper team is hiding the substance that some of their cooperators have provided to protect ongoing investigations.

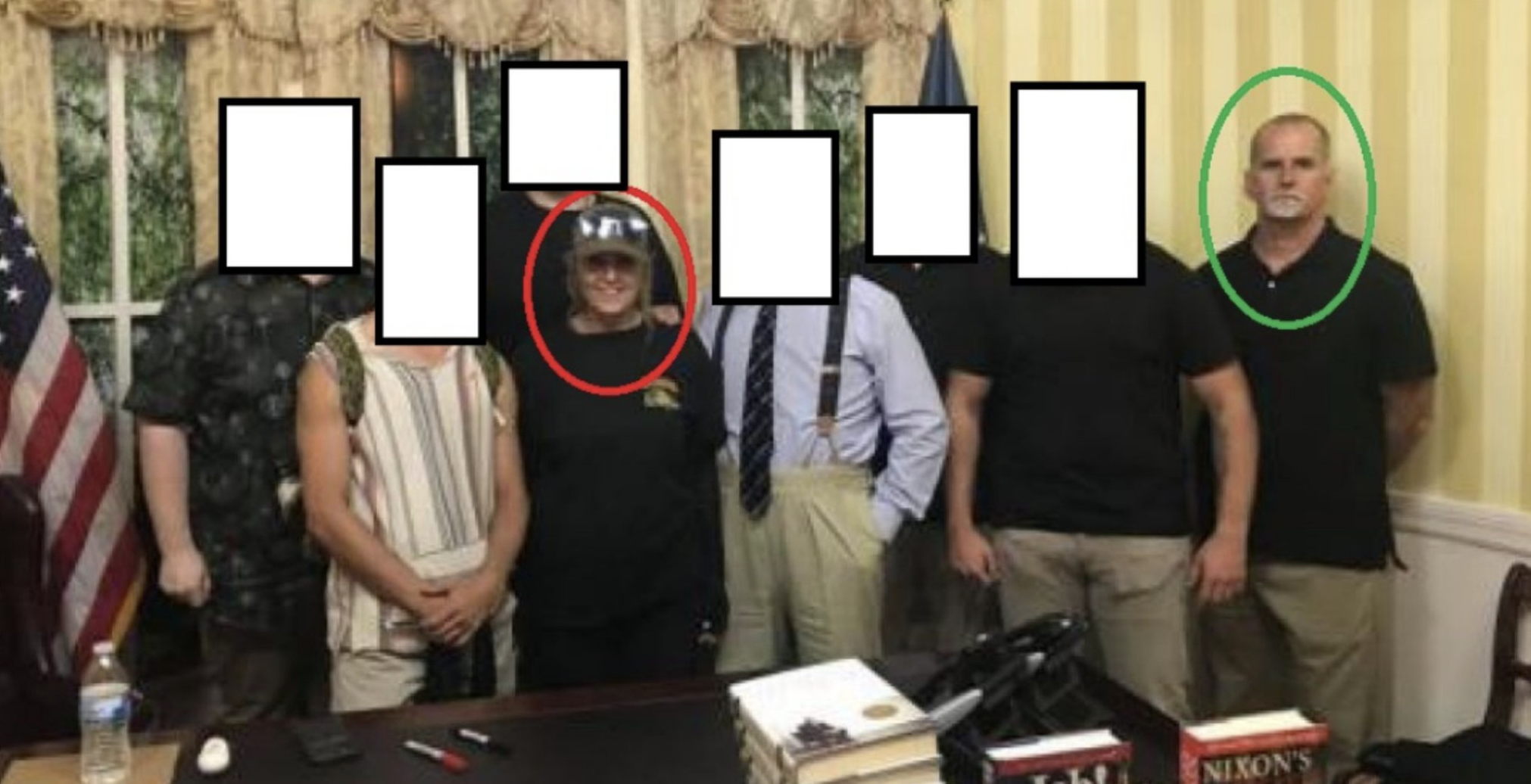

Mystery Green Berets

Then there’s a January 6 cooperation deal that has attracted almost no notice: that of Kurt Peterson. He’s a guy who broke a window of the Capitol and witnessed the shooting of Ashli Babbitt. Last December, DOJ was attempting to use the broken window to leverage him to plead guilty to obstruction as part of a cooperation deal. In September, he pled to trespassing with a dangerous weapon, one of the sweetest plea deals of any January 6 defendant, one that likely means he’ll avoid any jail time (which is consistent with how enthusiastically DOJ was pursuing his cooperation last year). In advance of his plea, the two sides got permission to seal two sentences in Peterson’s statement of offense.

Here, there are compelling interests that override the public’s presumptive right of access because the proposed plea agreement is conditioned upon Defendant’s continued cooperation with the government, and the statement of offense that accompanies the proposed plea agreement describes another individual who is under investigation for criminal wrongdoing on January 6, 2021. Publicly filing this information could lead to the identification of this individual and would be akin to a criminal accusation that could cause serious reputational or professional harm before formal charges are filed. Moreover, the need to protect the integrity of the ongoing investigation justifies the requested partial sealing. See United States v. Hubbard, 650 F.2d 293, 323 (D.C. Cir. 1980) (“As to potential defendants not involved in the proceeding …premature publication can taint future prosecutions to the detriment of both the government and the defense.”). Furthermore, the partial sealing is justified by the need to protect the Defendant’s safety in light of his ongoing cooperation. Washington Post, 935 F.2d at 291 (“the safety of the defendant and his family, may well be sufficient to justify sealing a plea agreement”). See also United States v. Thompson, 199 F. Supp. 3d 3, 9 (D.D.C. 2016) (“sentencing memoranda that include information regarding a defendant’s cooperation are often filed under seal.”).

[snip]

No alternative to sealing will adequately protect the due process rights of an unnamed defendant; preserve the integrity of the government’s investigation; and help ensure the safety of the Defendant.

The two sentences in Peterson’s statement of offense (which follow these two sentences) clearly relate to the three people with whom he traveled from KY to DC.

The defendant, Kurt Peterson, lives in Hodgenville, Kentucky. On January 5, 2021, the defendant drove from his home to the Washington, D.C. area with three other people,

[snip]

After leaving the Capitol Building, the defendant met back up with his traveling companions.

He got separated from them on the way to the Capitol though; his cooperation likely pertains to what he learned they (or one of them) had done on the trip back.

His arrest affidavit describes a recording he made on January 10, 2021, when he had gone on the run. It reveals that his three companions were all former Special Forces guys in their sixties.

To my family and friends who are able to see this, I am writing it with a voice recognition program while driving. I feel the need to keep moving and trying to keep my phone wrapped such that it can’t be traced most of the time. I was at our nation’s capital for the rally and watched the presentations at the ellipse prior to walking to the Capitol building with at least a million and a 1-1/2 to 2 million people.

The people that were there at the ellipse were peaceable and loving and supporting our country. The people that were at the capital were also primarily peaceful and loving our country. But when there are huge crowds and there are people that are inciting violence the crowds will many times be pulled in to this action.

I was with 3 men who had served our country in special forces. All of us in our sixties.

[snip]

Sadly I do not trust many branches or people in our government particularly the federal bureau of investigation. So at this time I am moving continuously and wrapping my phone in such a way that I hope it cannot be tracked. If for any reason I am not available to see you or meet with you again know that my intentions are to keep our country free of oppression by an over zealous government.

Yet no one knows who these three (or one particular) suspects were that made them or him so interesting to DOJ to merit this sweet plea deal or the year of effort to get it.

The thing is, the suspect in question must have already been charged and probably arrested. Before the plea hearing formally started, there was discussion of a “related case” designation, which would ensure that Judge Carl Nichols would preside over it, as well as Peterson’s. That would only happen if there were already another indictment.

Besides, the three guys who were with Peterson know they were with him; redacting that language doesn’t hide the cooperation from them, at all.

The relentless public roll-out of cooperators in the Oath Keeper case is the exception, not the norm (as Amit Mehta noted when Schaffer first pled guilty). Even those of us who follow closely are not seeing all of what’s going on, even in the overt crime scene prosecutions.

And Tarrio, himself a former snitch, knows better than most how useful disclosing such details may be to help others evade justice.